Bill Moyers on LBJ and ‘Selma’

After his online chat Tuesday, Bill had more to say about the Oscar-nominated film Selma, President Lyndon B. Johnson, the Voting Rights Act and how government has changed over the past 40-plus years. Read his Q & A below, and be sure to add your comments — as Bill said in the chat, he reads them all.

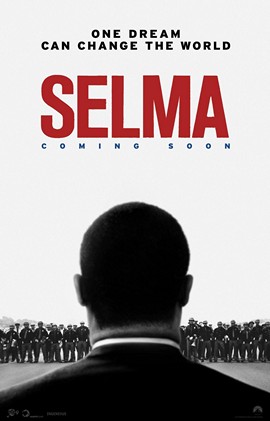

What did you think of the film Selma?

Bill: There are some beautiful and poignant moments in the film that take us closer to the truth than anything I’ve seen in other movies to date: the cruelty visited upon black people every day by whites and armed authorities; the humiliation they faced simply trying to register to vote (“Name all the county judges in Alabama!”); the courage and fear of those black people who put themselves on the line for freedom’s sake; the ambivalence in Martin Luther King Jr. as he faced the inescapability of leadership and constant threat of death. I cannot imagine the dread one had to subdue to step on that bridge that day.

Bill: There are some beautiful and poignant moments in the film that take us closer to the truth than anything I’ve seen in other movies to date: the cruelty visited upon black people every day by whites and armed authorities; the humiliation they faced simply trying to register to vote (“Name all the county judges in Alabama!”); the courage and fear of those black people who put themselves on the line for freedom’s sake; the ambivalence in Martin Luther King Jr. as he faced the inescapability of leadership and constant threat of death. I cannot imagine the dread one had to subdue to step on that bridge that day.

And I came out of the theater shaking my head in disbelief at the obscenity of the Republican Party as it has piously but insidiously taken up voter suppression as a priority. The Party of Lincoln? Of Emancipation? Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” of 50 years ago has now become their subliminal mantra: “Whites of America, Unite!” Back in the 1970s, in the early days of a resurging conservative movement, the late Paul Weyrich — godfather of the religious right and co-founder of the American Conservative Union, and of ALEC (the American Legislative Exchange Council, the powerful lobbying group for corporations and conservatives) – declared:

I don’t want everybody to vote. Elections are not won by a majority of people. They never have been from the beginning of the country, and they are not now. As a matter of fact our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.

So look who won the midterm elections as voter turnout fell to its lowest in 70 years: A coalition of suppressionists doing everything they can to make it hard for black and poor people to vote – and their big donors who give millions to drown out those very same voices. That’s “Free Speech” in the Roberts era.

As for how the film portrays Lyndon B. Johnson: There’s one egregious and outrageous portrayal that is the worst kind of creative license because it suggests the very opposite of the truth, in this case, that the president was behind J. Edgar Hoover’s sending the “sex tape” to Coretta King. Some of our most scrupulous historians have denounced that one. And even if you want to think of Lyndon B. Johnson as vile enough to want to do that, he was way too smart to hand Hoover the means of blackmailing him.

Then, casting the president as opposed to the Selma march, which the film does, is an exaggeration and misleading. He was concerned that coming less than a year after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there was little political will in Congress to deal with voting rights. As he said to Martin Luther King Jr., “You’re an activist; I’m a politician,” and politicians read the tide of events better than most of us read the hands on our watch. The president knew he needed public sentiment to gather momentum before he could introduce and quickly pass a voting rights bill. So he asked King to give him more time to bring Southern “moderates” and the rest of the country over to the cause, but once King made the case that blacks had waited too long for too little, Johnson told him: “Then go out there and make it possible for me to do the right thing.”

To my knowledge he never suggested Selma as the venue for a march but he’s on record as urging King to do something to arouse the sleeping white conscience, and when violence met the marchers on that bridge, he knew the moment had come: He told me to alert the speechwriters to get ready and within days he made his own famous “We Shall Overcome” address that transformed the political environment. Here the film is very disappointing. The director has a limpid president speaking in the Senate chamber to a normal number of senators as if it were a “ho hum” event. In fact, he made that speech where State of the Union addresses are delivered – in a packed House of Representatives. I was standing very near him, off to his right, and he was more emotionally and bodily into that speech than I had seen him in months. The nation was electrified. Watching on television, Martin Luther King Jr. wept. This is the moment when the film blows the possibility for true drama — of history happening right before our eyes.

So it’s a powerful but flawed film. Go see it, though – it’s good to be reminded of a time when courage on the street is met by a moral response from power.

You were involved in passing the Voting Rights Act? How do you assess its impact all these years later?

Bill: Just as Lyndon B. Johnson said at the time, the right to vote is “the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men.” We’re a different country today because of what happened then, obviously — with black Americans holding office all the way up to the president of the United States. After he signed the Voting Rights Act I asked LBJ if he thought this meant we’d have a black president in our time. He said no, we would have a woman first. Well, one down, another to go.

On the other hand, the reactionaries never give up. And the George Wallace of then would be pleased with the John Roberts of now. You may know the chief justice was a young lawyer in Ronald Reagan’s Department of Justice during the 1980s and doing everything he could to undermine the effectiveness of the Voting Rights Act. Roberts’ great conceit – shared by other conservative members of the court, including Clarence Thomas who keeps trying to kick over the ladder by which he himself was hoisted to prominence — is that racism is no longer the problem it once was. More or less what you can imagine a privileged elite of corporate lawyers would think, no? Read some of the memos and op-eds the younger Roberts wrote arguing for watering down the Voting Rights Act and you will understand why the conservative movement saw him as their new white hope on the bench. He seems to believe discrimination has to be intentional to be unconstitutional – that there’s no such thing as systemic racism, racism layered over decades or centuries. So we have now a one-time foot soldier in the conservative movement of legal resistance to equal rights occupying its commanding heights.

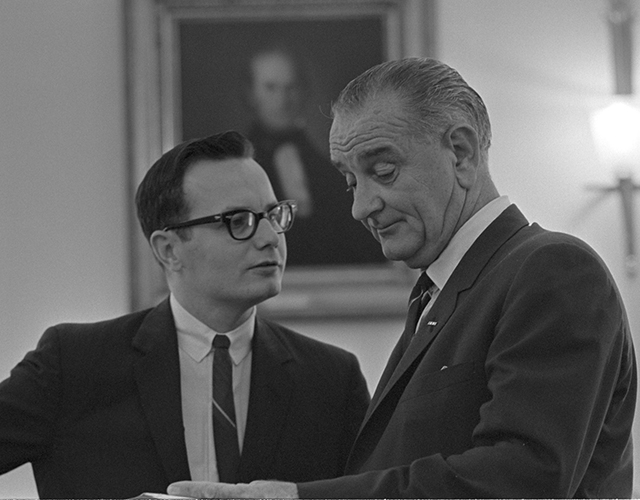

How do you remember LBJ?

(Note: Bill served as Lyndon B. Johnson’s domestic policy adviser in 1964-65 and his press secretary from 1965 to 1967.)

Bill: Lyndon B. Johnson owned and operated a ferocious ego. But he was curiously ill at ease with himself. He had an animal sense of weakness in other men — he wanted to know what you loved and what you feared and once he knew, he came after you. He was at times proud, sensitive, impulsive, flamboyant, sentimental, bold, magnanimous and graceful (the best dancer in the White House since George Washington); at times temperamental, paranoid, ill of spirit, vulgar. He had a passion for power but suffered violent dissent in the ranks of his own personality.

He could absolutely do the right thing at the right time — the reassuring grace, if you will, when he was thrust into the White House after Kennedy’s assassination; the Civil Rights Act of 1964; the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But when he did the wrong thing — escalating the Vietnam war — the damage was irreparable.

How would you describe the most striking and significant differences in our government that you have observed between the Vietnam era and today?

Bill: First, the sheer size and complexity of government — check out a recent post on billmoyers.com by John J. Dilulio Jr. reviewing Francis Fukuyama’s new book on the state of democracy; the two of them — Dilulio and Fukuyama — make this point brilliantly. I also just read a thoughtful piece by Charles Lane in theWashington Post arguing that the Great Society programs minted 50 years ago have mutated into sources of new and intractable problems, including their enormous cost; you can’t ignore the argument even as you also acknowledge how the giant tax cuts to the rich have cut government revenues that would help pay that cost. Everybody’s clamoring for more spending on infrastructure but hardly anyone is saying “Let’s raise the gasoline tax to pay for what all of us need and use!”

Second, the growth of the deep state — private instruments or agencies of power acting for and funded by the government (intelligence, the military, etc.). There’s a vast government we don’t see. A long-time senior Republican staff member of Congress, Mike Lofgren, wrote an extraordinary essay for billmoyers.com under the title The Deep State. Read it before you go to bed tonight. Rather, first thing in the morning. If you tackle it before bedtime, you won’t sleep.

And finally — although I should have started with this one: The triumph of money over every aspect of government. Money’s always been a force, but never to the extent it is today. We are just this close (I’m squeezing my index finger and thumb tightly) from oligarchy — the rule of the wealthy few for the purpose of increasing their wealth.