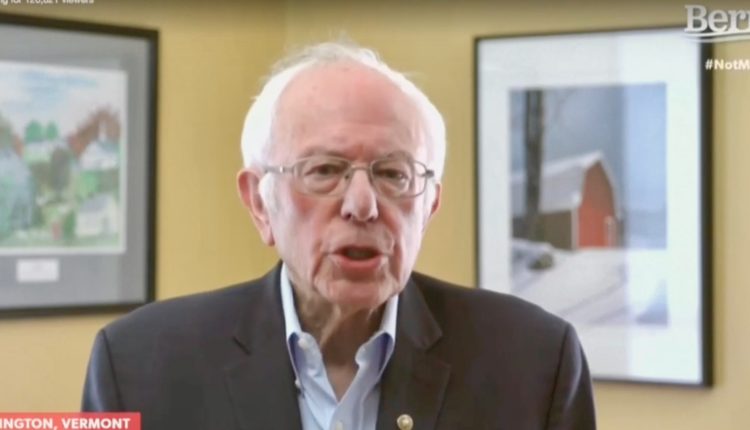

Bernie Sanders was right

By Elizabeth Bruenig / The New York Times

Bernie Sanders has ended his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination, which is a tragedy, because he was right about virtually everything. He was right from the very beginning, when he advocated a total overhaul of the American health care system in the 1970s. He remains right now, as a pandemic stresses the meager resources of millions of citizens to their breaking point, and possibly to their death. He was right when he seemed to be the only alarmist in a political climate of complacency. He is right now that he’s the only politician unsurprised to see drug companies profiteering from a lethal plague with Congress’s help. In politics, as in life, being right isn’t necessarily rewarded. But at least there’s some dignity in it.

In fact, both of Mr. Sanders’s presidential campaigns, beginning with his announcement in 2015 and ending here, were about dignity. Not only broad human dignity — Mr. Sanders’s relentless focus on the grim lives of the American poor, sick and disenfranchised is perhaps the greatest paean to the notion in modern political memory — but also the daily, personal sort we grant one another each time we tell the truth. Mr. Sanders is not and has never been a liar. His remarkable consistency over time, his notorious bluntness and his open disdain for sycophantic politics are all simply manifestations of that one critical fact. It made him an awkward fit for Washington, and it built him a movement.

A member of Congress for nearly 30 years, Mr. Sanders has been bitingly frank about the way that money strangles American democracy. Rich individuals with a vested interest in defanging egalitarian politics donate to campaigns, PACs, universities and think tanks in hopes of purchasing lawmakers’ loyalties and rigging the legislative process in their favor. These oligarchs — the Koch brothers, the Mercers and Michael Bloomberg, among others — exert control over our politics that far exceeds the one vote accorded to each citizen.

Mr. Sanders wagered that the only way to battle the leviathan was with sheer numbers. In 2019, 1.4 million individual donors from all 50 states sent the Sanders campaign some $96 million, without closed-door fund-raisers, hobnobbing in the Hamptons or groveling to billionaires. Mr. Sanders knows as well as everyone on Capitol Hill that you can’t really resist the people who sign your paychecks. He was just the only one willing to say it and to accept all that entailed.

Mr. Sanders was also honest about the unflattering facts of American life in a period of unusual liberal nostalgia for the way things used to be. In 2016, when Hillary Clinton ran on the premise, as opposed to Donald Trump’s, that America is already great, Mr. Sanders contended that just wasn’t so. America, he argued, is a place where the strong prey on the weak with almost total impunity, especially when that strength is wielded against workers, especially when those workers are undocumented immigrants, women, poor, sick, precarious.

And as Joe Biden prepares to mount a general election campaign based largely on the fantasy of going back to normal (meaning the Obama years), Mr. Sanders remains critical of life under the past administration. He contends that the bailouts bestowed upon Wall Street by the federal government during the 2008 financial crisis were a disaster that rewarded financial malefactors and that the fallout of the recession continues to crush average Americans under debt, poverty and stagnant wages.

None of this is pleasant to hear. And Mr. Sanders has never been a particularly mellifluous speaker. Much has been made in the past several years of his loudness, his anger, his bracing, impolitic bluntness. But that, too, is a sign of his respect for voters.

There is so little freedom in the world. Even here, now, in our celebrated liberal democracy, social mobility is incredibly limited compared to that in countries of comparable development, and there appears to be very little we can do about it. One freedom that cannot be taken from you is your freedom not to like the status quo — your freedom to be angry, disaffected, unimpressed, your refusal to be cajoled, soothed or consoled with small tokens of influence devoid of real power. Mr. Sanders, ill tempered and impatient with pleasantries, embodied that freedom, and he offered it to you.

None of this means you will get what you want, in politics or in life: Mr. Sanders did not win, after all. But he never lied, and he never pretended to like what is so clearly detestable or attempted to persuade any one of us that we ought to like it either. He was right to the end, and he refused to reconcile himself to the forces that eventually overtook him. It is hard to see him go. But there is at least some dignity in it.