An American ‘lost’ in Havana

HAVANA — Cuba is in fashion. Behind us are the years of solitude on an empty and dark stage. After Dec. 17, 2014, all the lights went on and focused on our country. The Americans want to come.

They wanted to come before, but now the fruit forbidden (still not ripe) by the U.S. government for so many years may soon be sampled in this “bubble lost in history,” where many say that we live.

And Americans want to come soon because “soon this place will be totally commercialized and I want to see it before it changes altogether.” So said Bill (not his full name), a 50-some American who visited Havana some days ago.

Bill comes from Atlanta, Ga., escaping for three days from a stressing routine, in which he needs to work almost 14 hours a day to pay for comforts he doesn’t have the time to enjoy.

“My life is the normal life of an ordinary American,” he says. “This month I was able to take a vacation because it’s a time when there isn’t much demand for me, but after September it will be impossible for me to get off work.”

“I work in catering, you know what I mean?”

I believe I do. Some days ago, a friend of mine, an engineer, told me that in none of the 28 countries that she has visited for reasons of work could she feel fulfilled in her profession and work only eight hours a day, as in Cuba.

Bill describes as “legal extortion” the fact that he has to pay medical insurance that is “ridiculously expensive” and that he cannot afford to reject.

“I could lose my job, be penalized, and so on. No other major, multicultural country in the world treats its citizens this way,” he says.

So he arrives in Cuba and feels “freedom” in every pore, notices the sharp difference between unlike ways of life.

“Over there, we have the money, but here, despite all the problems, the people seem happy,” he says.

“True, [in the U.S.] you have anything you can imagine — or at least most people can buy anything on credit — but in the end you live burdened by debt,” he says. “That’s because credit is nothing but debts. It appears that you have many things, but in reality nothing belongs to you.”

Bill spent so much time working that his information data bank contained little about Cuba, only that it was a place Americans couldn’t visit. So he landed in Cuba not knowing who is the country’s president (“What’s his name?”) or the fact that the naval base at Guantánamo Bay belongs to the island.

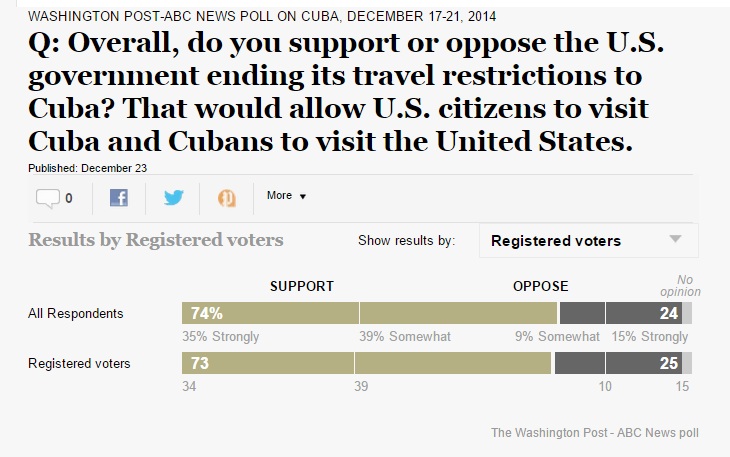

He also was unaware that it is the U.S. government — not the Cuban government — that prevents U.S. citizens from traveling to Cuba, even though they have every right to and a majority of Americans want to.

A study published in Social Times shows that Americans trust more the traditional forms of information — like television (75 percent) and the printed press (71 percent) — than the online media, although they perceive that the latter make Americans freer as citizens.

The media Americans trust the most have made them believe for years in “the dictatorship of the Castro brothers” and have created a vision of Cuba that does not go beyond the most basic stereotypes.

“I thought that it would be more difficult to come here, that they’d ask me a lot of questions, that soldiers would be waiting for me at the airport and all that. And since I can’t say that I’m a tourist, as I can in any other destination in the Caribbean, I was a little scared of what I might find. But nobody asked me what I was here for,” Bill says.

“Now I know it’s not Castro, it’s Obama,” he adds. “And I was amazed to find that out, because I don’t think it makes any sense.”

“Coffee is really good here”

At first, he was terrified. Cuba is a communist country, a dictatorship, “blah, blah, blah.” Besides, about to fly from Atlanta to Havana, he was going to enter a foreign country not knowing the language, not knowing where he would stay, not knowing anyone, “only with the assurance that a stranger would meet me at the airport, holding a sign with my name. It was crazy. Imagine.”

“So I said to myself, ‘What the hell!’ And two hours later, a polite man met me at the airport and took me to a private home where the landlady was very nice with me, where I’ve met many friends. Couldn’t have been better,” he says.

Bill is delighted with his fundamental discovery — Cuban people.

“I like the idea of staying in private homes, not in hotels. I like the hotels but I prefer to spend time with the people and discover places, because beautiful hotels I can go to in America.”

Yes, to them, America is the United States; to them, it’s the best country in the world.

Bill thought that he should hurry because Cuba was about to turn into another Cancún, into a great tourist destination without an identity, wholly globalized. But now he knows that that change will take decades, because, as he noticed, the tourism infrastructure must be rebuilt practically from zero.

“They need to build hotels, highways, connections, everything. Anf for that they’ll need a lot more than money from tourists; they will need billions of dollars.”

He can’t understand how people can live on 25 dollars a month. He can’t picture it. “How can you do it?” he keeps asking, trying to decipher a mystery that not even many Cubans can explain. At a dinner with friends, he learned more about Cuba “than what I would have learned from a hotel tour guide.”

“The people are spectacular; they look you in the eye at all times. They are very friendly, warm. Everywhere I’ve found good and charming people. They laugh a lot. Even the taxi driver was friendly with me, someone I didn’t know at all.

“I know that there are people who are friendly because you’re a tourist, as it happens in all other countries, and offer you cigars, rum, women, etc.

“But I refer to something else. It’s very easy to chat with anyone. And the women are so pretty! The truth is that the cigars don’t attract me as much as some of the women I’ve seen.

“In fact, I’m planning to return.”

Progreso Semanal/ Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists, so long as the source and author are identified.