The angry tide has washed into Chile

José Antonio Kast is a product of Chile’s long shadow, where the unresolved legacies of the military dictatorship seep into the present.

On 14 December, the predictable happened: José Antonio Kast, the candidate of the far-right Republican Party, prevailed over Jeannette Jara of the Communist Party of Chile by 58.16 percent to 41.84 percent. Kast ran as the candidate of the Cambio por Chile (Change for Chile) platform and was backed by all the parties of the traditional right and the centre-right. Jara, on the other hand, was the candidate of Unidad por Chile (Unity for Chile), which comprised the centre-left parties, including the bloc of Chile’s current president, Gabriel Boric, the Frente Amplio (Broad Front).

In the first round of the election, Jara had been the lead candidate with 26.58 percent of the vote, while Kast won 23.92 percent. But this was misleading. The two right-wing candidates who immediately endorsed Kast, Johannes Kaiser (13.94 percent) and Evelyn Matthei (12.46 percent), gave him an arithmetic advantage of 50.32 percent. The question for Jara was whether she could surpass 30 percent. That she ended up with over 40 percent is itself a remarkable achievement. It is not easy for the Chilean population, marinated in anti-communism for several generations (particularly during the military dictatorship from 1973 to 1990), to consider voting a Communist into the presidential palace, even if her opponent is a man of the extreme right.

Kast’s arrival in La Moneda, the presidential palace, is part of the Angry Tide that has been sweeping Latin America from El Salvador to Argentina. His victory is not unique. It follows the collapse of the liberal agenda, which tried to maintain rigid economic austerity policies alongside limited social programs, and is the result of the left’s failure to build a strong agenda to fulfill the demands of the social uprisings that have erupted against austerity and hierarchy.

Child of the Dictatorship

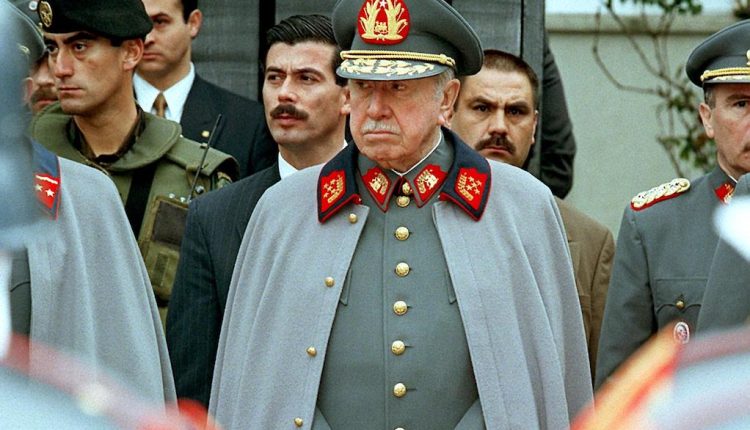

José Antonio Kast is a product of Chile’s long shadow, where the unresolved legacies of the military dictatorship seep into the present. Born in 1966 to a German immigrant family, Kast emerged from the conservative heartlands of Chilean politics, first as a member of the Independent Democratic Union, the party most faithfully aligned with Augusto Pinochet’s project. His political formation is inseparable from that history: an unrepentant defense of the neoliberal order imposed by force and a moral authoritarianism dressed up as “tradition”.

Kast’s father —Michael Martin Kast Schindele— served in the Wehrmacht(the German army) and was a member of the Nazi Party. After Germany’s defeat, Michael Kast fled Allied custody in Italy, returned to Bavaria, then escaped the postwar denazification process and emigrated to Argentina and then Chile via the Vatican’s ratlines. In Santiago in 1950, Kast started a sausage company and built a fortune. His elder son, Miguel Kast — a “Chicago Boy” — served as Minister of Labor and President of the Central Bank under the military government of General Augusto Pinochet. The entire family supported Pinochet. When asked about Pinochet by La Tercera in 2017, José Antonio Kast said, “I defended his government, but I never even had a coffee with him. You don’t have to be very imaginative to think that if he were alive, he would vote for me. Now, if I had met with him, we would have had a cup of tea at La Moneda.”

Kast cannot be held responsible for his father. He has said that Nazism is an ideology with which he disagrees, and one should take him at his word. On the other hand, the easy facility with which he embraces Pinochet’s military dictatorship should give one pause. During the social uprising in Chile in 2019, Kast reinvented himself as the defender of the ordinary Chilean against migrants, feminists, socialists, communists, and Mapuche demands against the cruel social order. Kast borrowed from the global far right: law-and-order fantasies, nostalgia for old hierarchies of race and gender, and a ruthless contempt for social movements that dare to challenge entrenched inequality.

What makes Kast dangerous is not his originality, for there is nothing original about his ideas or his place in society. It is his familiarity that is dangerous. Despite the end of the military dictatorship 35 years ago, the structures set in place by Pinochet remain. This includes the Constitution of 1980, which now appears eternal because two attempts to revise it (in 2022 and 2023) failed. Crucially, Chile’s reality includes property relations reorganized during the dictatorship to favor the oligarchy, including Pinochet’s own relatives. During the dictatorship, Pinochet privatized one of the major mining companies — Sociedad Química y Minera (SQM) — which was later taken over by Pinochet’s son-in-law, Julio Ponce Lerou (then married to Pinochet’s daughter, Verónica). This sort of dictatorship-driven piracy remained intact after the dictatorship ended (Pinochet’s granddaughter now runs the company).

These features of the oligarchy and its Pinochet-era consolidation are crucial to Kast’s prominence and rise. He speaks a language long used in Chile to justify this inequality: that markets are sacred, that discipline is virtue, and that memory must be silenced. In moments of crisis, figures like Kast do not arise by accident. They are summoned by elites when democracy threatens to become too democratic, when the people begin to ask for dignity rather than permission. He will be sworn in on 11 March 2026.

Will Chile Rise Again?

A massive social uprising that began in October 2019 brought together many sections of Chile’s society that had felt the hard edge of neoliberal austerity. This was not a spontaneous rebellion, but the product of decades of accumulated grievances rooted in inequality, privatization, and social humiliation, grievances that had long been contested by various social forces organized into movements and platforms. That protest led to the centre-left’s Gabriel Boric’s victory in 2021, but Boric’s government was simply unable to break with the consensus and to provide the country with a new agenda for new times. It was almost a caretaker government from one right-wing president (Sebastián Piñera, 2010-2014 and 2018-2022) to another. The streets are calmer now than they were in 2019, but the structural conditions that produced that uprising have not been dismantled.

When I met Boric before he took office, he was sure that his government would be able to reform the pension system and address the healthcare, education, and housing crises. Nothing was really achieved, and even constitutional reform failed. With the promise of social mobility no longer available to the population, particularly the youth, discontent rose. The centre-left lost its legitimacy, and that discontent once again turned to disillusionment. There is a widespread sense of political exhaustion and betrayal. Institutions appear incapable of translating popular demands into real change, reinforcing the idea that voting — even if compulsory — cannot inaugurate a new world. This demoralization is a real social force, one that led a large section of Jara’s voters to vote to block Kast rather than to vote for Jara with enthusiasm.

Chile’s median age is 38. Many young Chileans entered adulthood amid the social uprising over the past decade, then a pandemic, and finally, what appears to be permanent inflation. With the failure to ratify a new Constitution and Kast’s victory, this young Chilean voice for a different future is certainly going to feel muted. But it will not remain silenced for long. It will have to come to terms with Kast’s horrendous program: the continued militarization of the Mapuche territory in the south, the criminalization of protest, and the expansion of a state that prepares for containment, not redistribution. Kast’s agenda will not eliminate unrest but may postpone it for a while, only to sharpen its eventual return to the streets. When Kast sends the police to beat the protestors, his followers will undoubtedly take refuge in the language of legality, while his opponents will speak of the regime’s illegitimacy. If Kast cannot deliver policies to contain inflation and unemployment, inequality will rise and produce its own fury.

If a new social uprising does form, what will its core issue be? And will those who lead it be able to generate a credible political project capable of channeling that anger toward transformation? If there is no such project, a repeat of 2019 might move from explosion to disappointment and then to utter dejection. It will be up to Jara and others around her to craft an agenda to defend citizens’ constitutional rights against the Kast government and then to shape a project that is credible and desirable. The social uprising of 2019 is not a closed chapter; it is an unfinished sentence. Within that unfinished sentence were the Boric years (2022-2026), a delay more than anything. Dignity remains the demand. It may reassert itself, but only when patience runs out again.