The end of the “Hug Bibi” era

Former Obama deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes argues that Democrats have reached a moral, political, and strategic dead end on the Netanyahu government.

In his sweeping and unsparing critique of Democratic Party policy toward Israel, former Obama deputy national security adviser Ben Rhodes argues, in an opinion piece written for The New York Times, that Democrats have reached a moral, political, and strategic dead end. His core message is straightforward: the party must stop supporting Benjamin Netanyahu’s government — not out of ideological impulse, but because doing so contradicts Democratic values, undermines U.S. credibility, and increasingly alienates the voters Democrats need to win elections.

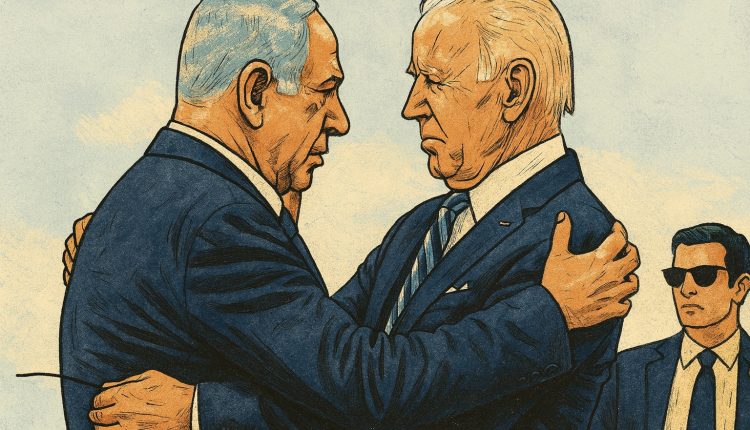

Rhodes begins with the emblematic moment that shaped the Biden administration’s posture: President Biden’s embrace of Netanyahu during his post–Oct. 7 trip to Israel. The “hug Bibi” strategy, as Rhodes explains, was supposed to give Washington influence over Israeli decision-making by providing unconditional support. Instead, he argues, it became a form of political self-deception — a belief that emotional solidarity could substitute for leverage. In practice, this approach “led the White House to provide a flood of weapons for Israel’s bombardment of Palestinians, veto United Nations Security Council resolutions calling for a cease-fire,” and even “ignore its own policies about supporting military units credibly accused of war crimes,” as Rhodes writes.

If the goal was influence, Rhodes says, the strategy failed. If the goal was political safety, it backfired. And if the goal was moral consistency, it collapsed under the weight of Gaza’s destruction.

The Disconnect Between Rhetoric and Reality

One of Rhodes’s most powerful arguments is that the Democratic Party has sheltered itself inside outdated talking points — “Israel is the only democracy in the Middle East,” “Israel has a right to defend itself,” “the Palestinian Authority must reform” — while the underlying conditions have fundamentally changed. He cites his own experience in the Obama administration, witnessing the expansion of settlements, the entrenchment of the blockade on Gaza, and the weakening of the Palestinian Authority.

By 2016, he writes, the “two-state solution” vocabulary had become “a smoke screen — a stale formula to be used in Washington rather than a description of reality in the Middle East.” The Democratic message calcified even as Israeli politics moved sharply right and Netanyahu openly rejected Palestinian statehood.

This gap between message and reality is not simply a foreign-policy problem; it’s a political one. Rhodes notes that only a third of Democrats now have a favorable view of Israel, down from 73 percent in 2014. Among Jewish Americans — a constituency Republicans claim will abandon Democrats over Israel — large majorities continue to vote Democratic while also believing that Israel committed war crimes in Gaza. And the youngest voters, whom Democrats cannot afford to lose, are the most skeptical of U.S. support for Netanyahu.

In other words, the old script is no longer just outdated — it’s counterproductive.

The Consequences of Silence

Rhodes argues that Democrats’ unwillingness to confront Netanyahu has damaged their broader claims about democracy and human rights. How can a party defend a “rules-based order,” he asks, while supplying weapons for actions that international human rights organizations and U.N. investigators have described as potential genocide? How can Democrats oppose authoritarianism globally while avoiding criticism of Netanyahu’s attempts to weaken Israel’s judiciary and empower extremist settler groups?

The result, he says, is a party trapped between its own values and its fear of political backlash — while groups like AIPAC, increasingly aligned with Republican donors, target Democrats who dissent. Rhodes points to primary challenges funded by Republican money as evidence that deference to AIPAC no longer protects Democrats; it merely binds them to an agenda out of step with their base.

What Comes Next

Rhodes offers a clear alternative path: stop providing military assistance to a government accused of war crimes; support the International Criminal Court’s investigations “whether it is focused on Vladimir Putin or Benjamin Netanyahu”; oppose annexation of the West Bank; and invest in building a credible Palestinian leadership that can pursue statehood.

None of this, he concedes, will magically solve the conflict. But it would realign the party with its stated ideals — and with its voters. Rhodes emphasizes that taking a principled stand is not only morally urgent but politically viable. Jewish Americans have consistently rejected the Republican strategy of wielding Israel as a wedge issue. Young voters, progressives, and many independents respond to authenticity and courage, not triangulation.

He cites the example of Zohran Mamdani, New York’s mayor-elect, whose progressive views on Israel triggered establishment backlash but ultimately strengthened his image as a candidate with convictions. By contrast, the pro-Netanyahu posturing of his opponent — including Andrew Cuomo’s volunteering for Netanyahu’s legal defense team — “did not come across as particularly courageous or authentic.”

A Moral Reckoning and a Strategic Warning

The strongest thread running through Rhodes’s analysis is that the safest political path is not always the wisest. The Democratic Party’s fear of angering Netanyahu, or AIPAC, or certain donors, may have seemed like prudent risk management. But this instinct, Rhodes argues, produced a “moral stain that cannot be removed,” widened generational divides among Democrats, and emboldened an Israeli leader who has repeatedly undermined Democratic presidents.

“The hug Bibi strategy showed that the seemingly safest path can become the most dangerous,” he writes — for U.S. foreign policy, for global democracy, and for the party’s political future.

In the age of rising authoritarianism, Rhodes insists that Democrats cannot tell Americans to confront hard truths while refusing to confront one themselves. His final message to his party is both a warning and a challenge: “Sometimes, to win, you must show that there are principles for which you are prepared to lose.”

It is a call for consistency, courage, and clarity — qualities that, Rhodes suggests, have been missing from Democratic policy on Israel for far too long.