The CIA-in-Chile scandal at 50

Washington, D.C., September 9, 2024 – Fifty years ago, as the New York Times prepared to break a major exposé on CIA covert operations in Chile, the architect of those operations, Henry Kissinger, misled President Gerald Ford about clandestine U.S. efforts to undermine the elected government of Socialist Party leader Salvador Allende, documents posted today by the National Security Archive show. The covert operations were “designed to keep the democratic process going,” Kissinger briefed Ford in the Oval Office two days before the article appeared fifty years ago this week. According to Kissinger, “there was no attempt at a coup.”

“I saw the Chile story,” Ford told Kissinger on September 9, 1974. “Are there any repercussions?” Kissinger replied: “Not really.”

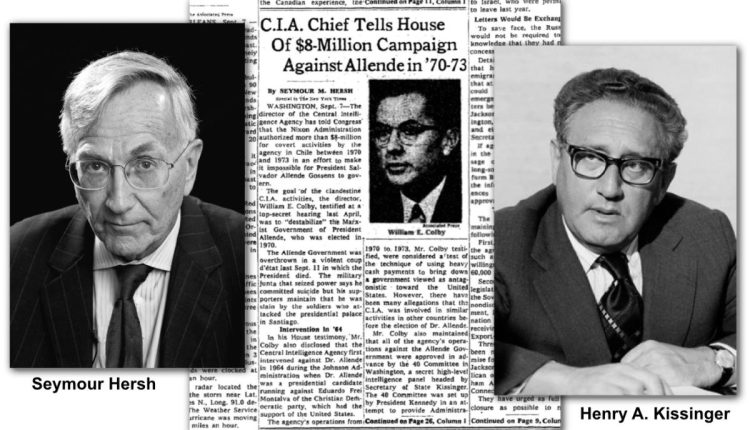

In fact, the front-page story written by investigative reporter Seymour Hersh—“C.I.A. Chief Tells House Of $8 Million Campaign Against Allende in ‘70-’73”—set in motion the biggest scandal on covert operations the intelligence community had ever experienced. Hersh’s September 8, 1974, article led directly to the formation of a special Senate committee, chaired by Senator Frank Church, that conducted the first major investigation of CIA covert actions in Chile and elsewhere and that was the first congressional body to evaluate the role of secret, clandestine operations in a democratic society. The political repercussions forced President Ford to publicly acknowledge the CIA operations in Chile while forcefully denying they had anything to do with fomenting a coup. The president’s White House lawyer subsequently advised Ford that his statement “was not fully consistent with the facts because all the facts had not been made known to you.”

At a September 16th press conference, Gerald Ford became the first president to publicly acknowledge and defend CIA covert operations, which he characterized as limited to protecting Chilean democratic institutions from the threat of Allende. He stated that the CIA actions were “in the best interest of the people in Chile, and certainly in our best interest.” (See timecode 11:55 in tape for Ford’s statement.)

The Senate investigation, which also revealed CIA assassination plots against foreign leaders, and a similar investigative effort in the House of Representatives led to legislation to enhance checks and balances on CIA operations and curtail the ability of future presidents to “plausibly deny” covert action programs abroad. White House documents reveal the acute consternation expressed by Ford and Kissinger that covert operations might be restrained. “We need a CIA and we need covert operations,” Ford told his Cabinet nine days after the Times exposé was published. The article and a flood of follow up CIA stories by Hersh, as Kissinger later conceded in his memoirs, “had the effect of a burning match in a gasoline depot.”

THE LEAK THAT CHANGED HISTORY

The Hersh story was based on a summary of secret testimony by CIA director William Colby and a legendary agency official, David Atlee Phillips, who provided an overview of covert operations against Allende in Chile during an executive session of the House Armed Services Committee on April 22, 1974. According to the summary, Colby informed the Committee that between 1962 and 1973, the ultra-secret “40 Committee,” which oversaw covert operations, had authorized the CIA to spend $11 million in Chile, including $8 million to “destabilize” the Allende government and “to precipitate its downfall.” The summary stated that “the agency activities were viewed as a prototype, or laboratory experiment, to test the techniques of heavy financial investment in efforts to discredit and bring down a government.”

The summary was drafted by a liberal congressman from Massachusetts, Michael J. Harrington, who had heard about Colby’s TOP SECRET testimony and requested special permission to review it. Harrington read the 48-page hearing transcript twice—on June 5, and June 12, 1974—and realized Colby’s testimony clearly contradicted previous denials by Kissinger and top CIA officials (during earlier hearings on the CIA and ITT’s operations in Chile) that there had been any covert efforts to undermine Allende.

Harrington shared his concern that CIA officers had committed perjury with Senator Frank Church’s staff director, Jerome Levinson. In his unpublished memoir, Levinson recalled that Harrington “asked what I thought he should do.” Levinson recommended that Harrington write a letter to the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Senator William Fulbright, requesting a full inquiry into the CIA’s role in Chile. On July 18, 1974, Harrington sent a lengthy letter to Fulbright, providing a summary of the secret CIA testimony and concluding that Congress and the American people “have a right to learn what was done in our name in Chile.”

After it became clear that Fulbright was not inclined to order a major investigation into the CIA role in Chile, Levinson decided to take the audacious step of calling attention to Colby’s still-secret testimony: he leaked the Harrington letter to Seymour Hersh. In early September, after lunch with Hersh at Jean-Pierre’s, a swanky D.C. restaurant, Levinson slipped Hersh a copy of the Harrington letter. On September 5, 1974, Hersh began calling State Department officials for comment on his forthcoming scoop, setting in motion a flurry of White House meetings, briefings and reports on what information Hersh might have obtained. On September 8, the Times published the story on the front page of its Sunday newspaper, generating a major scandal and eventually resulting in the prosecution of former CIA director Richard Helms for lying to Congress.

REACTION OF THE CIA’s CHILEAN AGENTS

The leak of Colby’s testimony forced the CIA to urgently contact its Chilean agents to ascertain the repercussions of the Hersh revelations on its network of assets and informants. In a revealing secret report four days after the Timesarticle appeared, the CIA station transmitted the reactions of several Chilean operatives—identified by codenames such as FUBARGAIN, FUPOCKET and FUBRIG—who were embedded inside the Chilean military, the Chilean Christian Democrat political party, and the El Mercurio newspaper, which the CIA had financed as a bullhorn of opposition to the government of Salvador Allende. “Following Station agents were contacted, period 8-10 September, in connection with referenced revelations,” the Santiago Station informed CIA headquarters.

The agent codenamed “FUBRIG-2 “took the news calmly but was most concerned about implications of efforts of revelations and expressed opinion that system in Washington should be changed to prevent such leaks,” the CIA reported. “He was relieved that El Mercurio was not mentioned by name.”

According to this cable, the agent inside the Chilean military, FUBARGAIN-1, told the CIA that “General Pinochet did not seem very upset but [had] commented … that the disclosure ‘seemed to be a dumb thing to do.’” But the same agent told the CIA that other younger Chilean military officers interpreted the leak as a deliberate attempt to “damage [the] Junta and falsely cast doubt on their independence and role in bringing down Allende.” “Sum is that Chilean officer corps becoming increasingly baffled and resentful about U.S., according to this source.”

STILL-SECRET DOCUMENTS

Fifty years after the scandal broke over CIA operations in Chile, Colby’s original testimony before the House Armed Services Committee remains classified, as does the entire 48-page transcript of the closed hearing. Last year, the Chilean government officially requested that the Biden administration declassify those records as a gesture of “declassification diplomacy” for the 50th anniversary of the coup, but the CIA proved to be uncooperative.

“For the sake of historical accountability, it is imperative that the CIA declassify Colby’s testimony on Chile, as well as other relevant documentation,” stated Peter Kornbluh who directs the Archive’s Chile Documentation Project. As the 50th anniversary of the formation of the special Senate Committee to Study Government Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities approaches in January 2025, the Archive also called on Senate leaders to initiate the release the Church Committee’s voluminous investigative archives on Chile and other countries targeted for covert regime change operations.

“A half century of secrecy surrounding these records,” Kornbluh noted, “must come to an end.”

In April 1974, CIA director William Colby appeared at a closed, executive session of the House Armed Services Committee and provided a lengthy summary of CIA covert operations in Chile between 1970 and 1973. Representative Michael J. Harrington, a liberal congressman from Massachusetts, obtained permission from committee chairman Lucian Nedzi to review Colby’s classified testimony. Harrington then wrote this summary of the testimony in the form of a letter to the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, William Fulbright. The summary describes the CIA’s $8 million clandestine campaign to “destabilize,” according to Harrington, the elected government of Salvador Allende. It identifies, for the first time, the “40 Committee” chaired by National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger as overseeing these covert operations to undermine Allende.

When Senator Fulbright failed to respond to Harrington’s call for hearings and a major investigation into CIA operations in Chile, in early September 1974 a ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations staff, Jerome Levinson, quietly slipped a copy of the Harrington letter to investigative journalist, Seymour Hersh. Hersh’s September 8, 1974, front page story in the New York Times—“C.I.A. Chief tells House Of $8 Million Campaign Against Allende, 70-73,”—was based on Harrington’s summary in the letter.