Sony and the music business in Cuba

By Leslia Peña Sepúlveda, Luis Dariel Pinto Delgado, Vladimir R. Mesa Boissalier and Yaisel Antonio Lambert Robert

HAVANA — The expansion in cultural exchanges between Cuba and the United States attracted the multinational Sony Music Entertainment and dozens of other famous companies. On Sept. 15, 2015, one year ago, Sony signed contracts with the Recordings and Musical Editions Enterprise (EGREM) for the international distribution of Cuban music.

The pact represents one of the few changes (and the most significant one) in the musical scene, offering its protagonists and creations a thread of hope to gain a well-deserved recognition in the main international circuits. But the little information provided, the pact itself, and the document’s clauses constitute an enigma.

“Sony’s strategy was to access digital contents to an extent that — before this moment in U.S.-Cuba relations — was unimaginable. What they sought was to use the good music made by EGREM to take it to the world,” said EGREM’s legal advisor, Ernesto Reyes Perea.

Some Cuban musicians have expressed their apprehension. “I am very skeptical of the future results of this contract with Sony and its alleged benefits for Cuba and its artists. There is a risk that we be hired and then Sony shelves our recordings to eliminate competition for the musicians in its repertoire,” says singer Luna Manzanares.

The EGREM catalog contains audio recordings dating to 1960. The fact that one of the largest multinational record companies is now interested in Cuban music depends to a great degree on the political relationships Cuba has maintained in recent times. Above all, on the cultural values that exist on the island.

Perhaps in that multinational interest the good Cuban music doesn’t fit at all.

“I recommend to all musicians to study the different models that are appearing worldwide for the distribution of their music,” says Darsi Fernández, representative of SGAE in Cuba (Spanish General Society of Authors and Publishers). Sony’s “is not necessarily the best model, because there are authors for whom it is better that their work be widely distributed through the social networks rather than a major record company.”

Musicians such as Roxana Iglesias (director of the group Frasis) and Lázaro Peña (director of the group Novel Nube Roja) say that, although both are members of recording companies such as EGREM, most of the promotion of their products, from the start of their careers, has been done through personal enterprise, using channels that are more accessible to the public, such as the social networks iTunes and Spotify.

Old-fashioned mechanisms for musical promotion

Although it isn’t considered by the Ministry of Culture “or by the cult of Cuban record companies,” as Reyes Perea says, most of the music we hear in Cuba is reggaeton. Its fast and direct lyrics, its catchy rhythm, and the ways its creators have found to promote their productions are factors that have moved this genre to the top of the music market.

On the other hand, reggaeton producers have to deal with complex and senseless mechanisms.

Entities such as the Cuban Agency for Musical Copyrights (ACDAM) and SGAE have more than 16,500 members who are Cuban musical creators, and have the power to collect commercial royalties, explains René Hernández Quintero, the ACDAM’s director general.

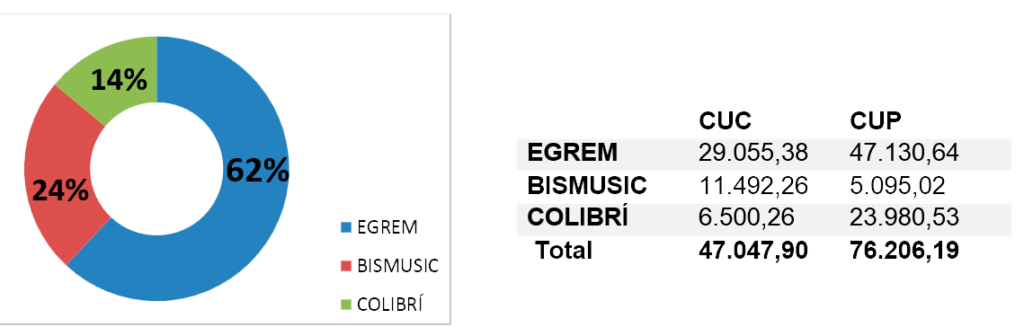

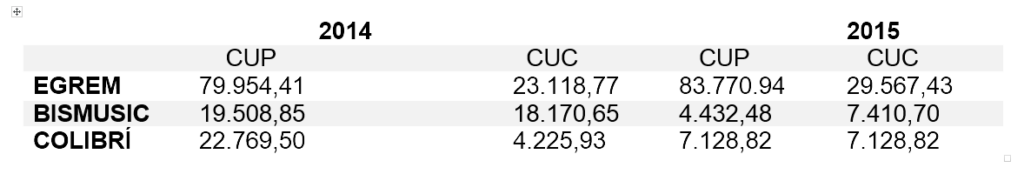

According to the traditional scheme in Cuba, access to the musical works is gained through the record companies that support CDs, DVDs and Mp Digital. The companies that bill the most in Cuba are EGREM, BisMusic and Colibrí. Selecting the artists and their repertoires, guaranteeing the production and marketing of the music and distributing the product are the tasks of these record companies, which in 2015 billed about 48,000 convertible pesos (CUC) and 77,000 national pesos (CUP).

From reading the statistics provided by the Cuban Copyrights Agency, we infer that the low cash return is due to the prices of the disks — inaccessible to most Cubans — and the insufficient promotion by the Cuban record companies.

On the other hand, alternative spaces for distribution and sale have grown wider, such as “the package” and the points of sales for records, which become intermediaries between the musical creator and his public in a legal/illegal area.

“The famous ‘package’ gives promotion to all of us musicians,” said singer Luna Manzanares.

It is well known that Cuba’s economic woes have caused, among other problems, the physical support for Cuban music through record companies to become almost nonexistent.

“The reality is that in Cuba we don’t have a nationwide digital environment that allows the distribution of music. What has happened in the private sector is just a kind of analogy to what might happen in Cuba if that environment existed,” reflects Reyes Perea.

The main sources of employment for musicians are live performances. The costs of these forms of promotion should be assumed by the record companies or the specialized entities, whose function it is to manage the hiring of technical equipment for audio and instruments, lodging, transportation and promotion.

Although the business is financially profitable for the Cuban economy, the spaces that now exist for musical forms that are not popular are insufficient.

“An artist has to do all the promotion, fill the venues and — if not enough people show up — the artist goes down the tubes,” says singer Enid Rosales.

In essence, the good Cuban music, its prestigious or popular creators, the record companies and the distribution centers need to join together to become an efficient machine for the distribution of the Cuban musical product. But the present situation does not leave much space for this ideal picture and raises numerous challenges. In this situation, reinvention is one of those challenges.

*This article was presented in June during a workshop at the José Martí Institute of Journalism.