Warning signs on the road to ‘change’ in Argentina

Imagine a U.S. presidential candidate who met with the Russian government and repeatedly accused them of being “too soft” on President Obama. A candidate who told Russia’s foreign minister of the “need to set limits” on the White House’s “misbehavior,” and that the Russians’ “silence” on the “abusive mistreatment it [Russia] suffered” at the hands of the Obama administration “had encouraged more of the same.”

Would Americans trust such a candidate? OK, that’s a rhetorical question. But in Argentina, it’s real.

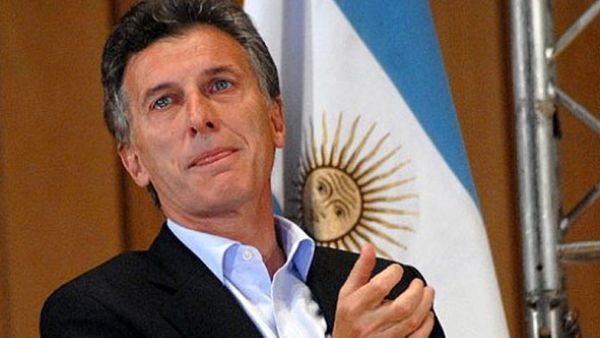

Mauricio Macri (photo at top), a right-wing businessman from one of the country’s richest families, is running for president in elections this Sunday. According to leaked documents from the U.S. Embassy, published by WikiLeaks, this is the conversation he had with the U.S. ambassador and the U.S. State Department official in charge of Latin America. He was very concerned that Washington was “too soft” on Argentina and was encouraging “abusive treatment” of the U.S. at the hands of the Argentine government.

The analogy is not perfect, since the current Russian government has never played a major role — or any role, for that matter — in wrecking the U.S. economy and creating a Great Depression here. But the U.S. Treasury Department, which was the IMF’s decider during Argentina’s severe depression of 1998-2002, did indeed exert an enormous influence on the policies that prolonged and deepened that depression. Argentines are not holding a grudge, but neither would they want the U.S. to again play a major role in their politics or economic policy.

But there are other reasons to worry about Macri’s intentions that hit closer to home. In his conversations with U.S. officials, in 2009, he referred to the economic policies of the Kirchners — Néstor Kirchner, who was president from 2003-2007, and his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who was elected in 2007 — as “a failed economic model.” He has made similar statements during the campaign, and although he has often been vague, he has indicated that he wants something very different, and considerably to the right of current economic policy.

It is worth looking at this much-maligned record of the Kirchners, especially since Daniel Scioli, who is the candidate of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her “Front for Victory” alliance, represents some continuity with “Kirchnerismo.” Macri’s coalition is called “Cambiemos,” or “Let’s Change.”

From 2003-2015, according to the IMF, the real (inflation-adjusted) Argentine economy grew by about 78 percent. (There is some dispute over this number, but not enough to change the overall picture.) This is quite a large increase in living standards, one of the biggest in the Americas. Unemployment fell from more than 17.2 percent to 6.9 percent (IMF). The government created the largest conditional cash transfer program in the Americas for the poor. From 2003 to the second half of 2013 (the latest independent statistics available), poverty fell by about 70 percent and extreme poverty by 80 percent. (These numbers are based on independent estimates of inflation.)

But these numbers do not describe the full magnitude of the achievement. As I describe in my book, Failed: What the ‘Experts’ Got Wrong About the Global Economy (Oxford University Press, 2015), Néstor Kirchner took office as the economy was beginning to recover from a serious depression, and it took great courage and tenacity to stand up to the IMF and its allies, negotiate a sustainable level of foreign debt (which involved sticking to a large default), and implement a set of macroeconomic policies that would allow for this remarkable recovery. It was analogous to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s leadership during the U.S. Great Depression, and like Roosevelt, Kirchner had the majority of the economics profession against him — as well as the media. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner also had to fight a number of battles to continue Argentina’s economic progress.

In the last four years, growth has slowed, inflation has been higher, and a black market has developed for the dollar. Some of this has been due to a number of unfavorable external shocks: the regional economy will have negative growth this year (Argentina’s will be slightly positive); Argentina’s biggest trading partner, Brazil, is in recession and has seen its currency plummet; and in 2014 a New York judge of questionable competence made a political decision to block Argentina from making debt payments to most of its creditors. So, despite the overall track record of 12 years of Kirchnerismo delivering a large increase in living standards and employment, and successful poverty reduction, there are significant problems that need to be fixed.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan ran for president of the United States in the midst of a recession and inflation passing 13 percent. He, too, promised change and he delivered it — and ushered in an era of sharply increased inequality and other social, political, and economic maladies from which America is still suffering. Just look at his proud progeny in the Republican presidential debates.

Macri probably does not have Reagan’s talent as an actor and communicator to radically transform Argentina and reverse most of the gains of the last 13 years. But it seems likely from the interests that he represents, and his political orientation, that Argentina’s poor and working people will bear the brunt of any economic adjustment. And there is a serious risk that by following right-wing “fixes” for the economy, he could launch a cycle of self-defeating austerity and recession of the kind that we have seen in Greece and the eurozone.

The Kirchners also reversed the impunity of military officers responsible for mass murder and torture during the dictatorship, and hundreds have been tried and convicted for their crimes. Macri has dismissed these unprecedented human rights achievements as mere political showmanship. His party also voted against marriage equality, which was passed anyway, making Argentina the first country in Latin America to legalize same-sex marriage.

“Let’s Change” is an appealing slogan, but the question is “change to what?”

Mark Weisbrot is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., and the president of Just Foreign Policy.

(From The Huffington Post)