Cuba’s demands for reparations and closing of Guantánamo are reasonable

President Obama initiated a historic change when he decided last December to begin normalizing relations with Cuba. It was an acknowledgment that more than half a century of trying to topple the Cuban government, through invasion, assassination attempts, economic embargo, and other — mostly illegal — efforts had failed. It was also a concession to the majority of the hemisphere, which had informed Washington in 2012 that there would not be another Summit of the Americas without Cuba.

It was not necessarily a change in U.S. objectives, as a number of statements from the U.S. government indicate that the goal of normalizing relations and expanding commerce with Cuba is still “regime change” by other means. But it is nonetheless a major step forward, after the U.S. had been isolated in the entire world on this issue for decades, with repeated votes against the embargo at the U.N. general assembly — such as last year’s tally of 188-2 (only Israel voted with the U.S.).

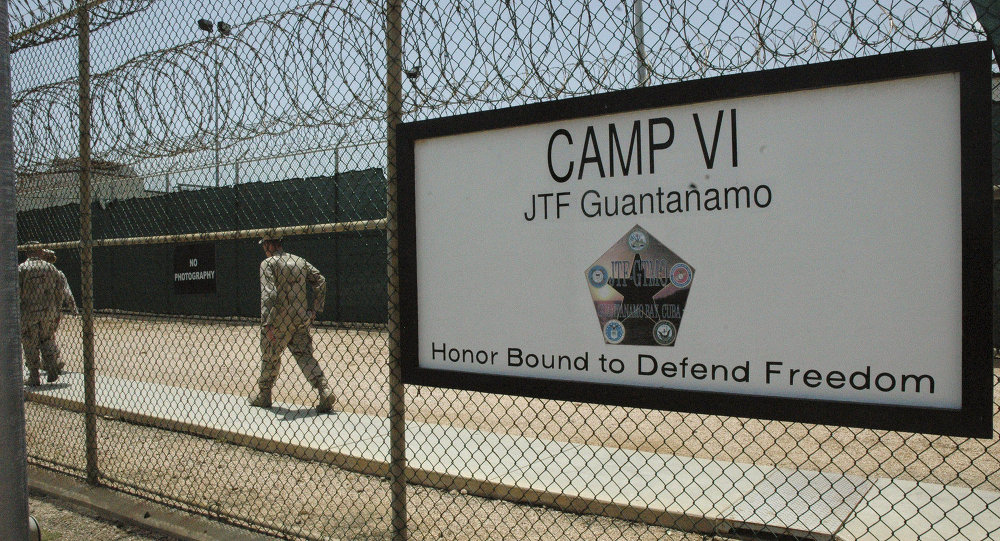

Last week, the Cuban government reiterated its position that in order for relations to be normalized, the U.S. must not only end the embargo but pay compensation for the damage that it has caused to Cuba and its people over the past 54 years. Cuban President Raúl Castro also reminded Washington that the Guantanamo prison and military base must be closed and the land returned to Cuba.

These are entirely reasonable requests from Cuba. The U.S. forced Cuba to accede to the military base in 1903, as well as grant permission to the United States to intervene in its internal affairs, as a condition of its “independence.” Furthermore, even if one ignores the how the lease originated, it was granted for a naval and coaling station – not a prison. So the U.S. is violating the terms of the lease, just as if someone rented a residential apartment and used it to sell drugs. Guantanamo is even more of an offense to Cubans, since it is an illegal prison that has become infamous for its torture and abuse of prisoners, the majority of whom have been cleared for release or have insufficient evidence against them to be prosecuted.

The Cuban demand for reparations is equally sensible. The 54-year embargo has caused tens of billions of dollars of damage in Cuba through shortages of food and medicine, infrastructure needs (including for clean water), foreign investment that was prevented, and other economic and health effects. The damages are difficult to estimate but certainly many times larger than those claimed by U.S. businesses and individuals who lost property in the years following the revolution.

Washington is unlikely to acknowledge that it owes reparations for its crimes against Cuba, partly because of fear that it would open the floodgates of demands from nations where the U.S. government has contributed to mass slaughter and destruction during the same era: Guatemala, Haiti, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Iraq — to name a few. Unlike Japan, for example, where there is widespread recognition that its 20th century aggressions against other countries were wrong, in the U.S. the official view is still something like Monty Python’s “let’s not argue about who killed who.” Bill Clinton is apparently the only modern U.S. president who expressed regret for any of these crimes, apologizing to Guatemala for the U.S. role in the long genocide there from the 1950s through the 1980s. But his statement was mostly ignored and quickly forgotten. So it is good that the Cubans are raising the issue of reparations: There was no more excuse for the embargo than for the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq, and having a sovereign state that is negotiating the normalization of its relations with the United States demand compensation will help increase awareness of this debt that Washington owes to many countries.

###

Mark Weisbrot is codirector of the Center for Economic and Policy Research (cepr.net).

(This article was first published in The Philadelphia Inquirer.)