The Francis effect and Dorothy Day

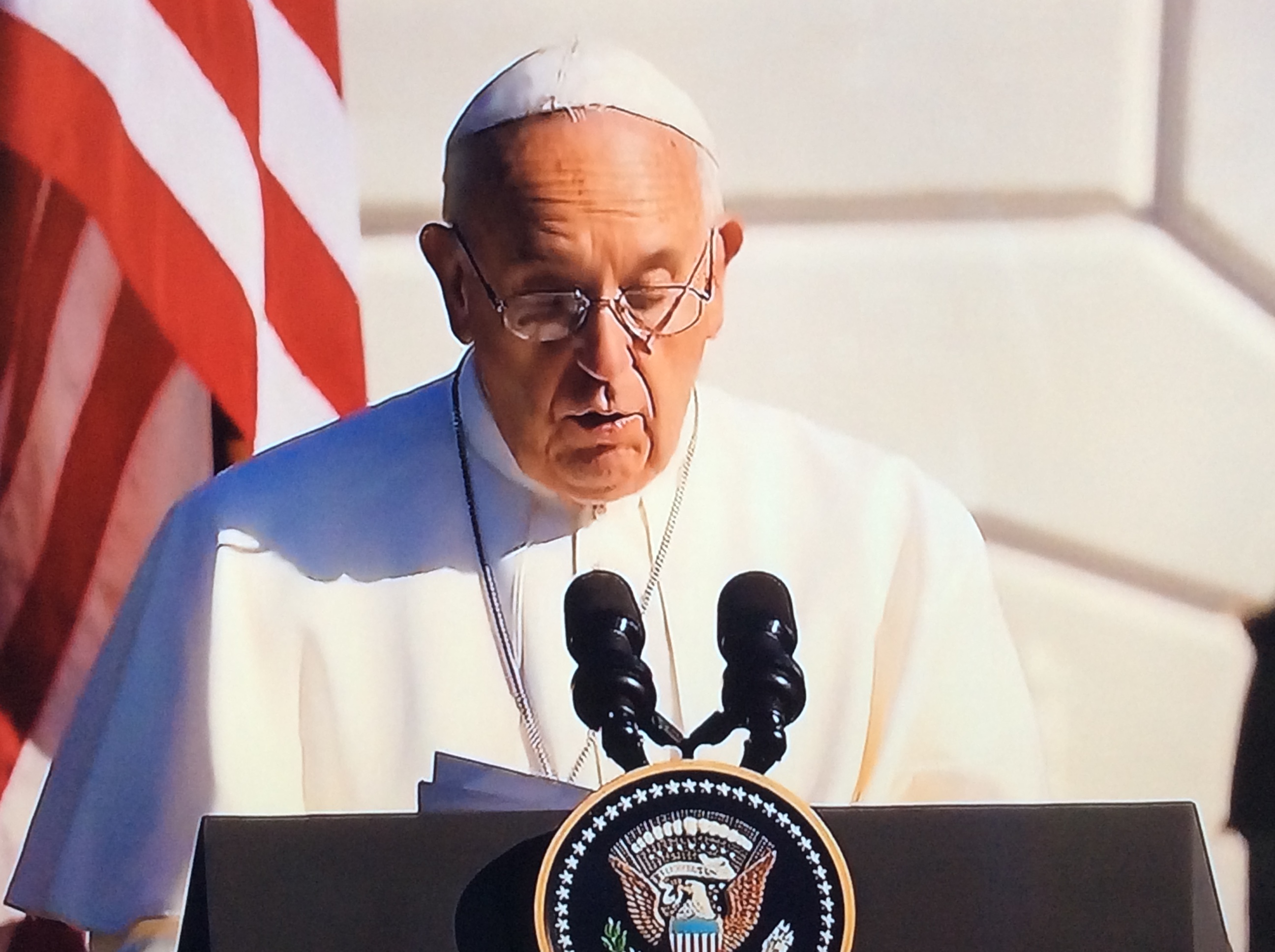

HAVANA — With incredible elegance and subtlety, Pope Francis left no stone standing on his journey to Washington and New York.

By that we mean that our friend Bergoglio plunged into the core issues of our time and world both in the U.S. Congress and the United Nations General Assembly. And the big question by the media and some of our readers is What will the Francisco effect be?

Will there be an effect? Will it remain only in that irrepressible moment when several legislators shed a tiny tear, dabbed quickly with silk handkerchiefs? Odd, because the possibly televised tears of the powerful, even if genuine, sell an image (in our world, everything is exploitable.)

After they dry those tears, they sip a scotch and period, because the world skein is so tangled and the thread is so perfectly concentrated in so few hands that hold the world’s economic and financial power that they end up concluding: “What Francis wants and I applaud, I cannot bring to pass.” Did Bergoglio talk to prisoners who live behind invisible bars?

In Congress and at the U.N., under his words, in them and above them beat the plea to go from the beautiful and promising accords to their concretion. According to the Bible, in the beginning was the Word, which is an act, in this case the creation of the universe, an act of loving creation by God, according to the most orthodox interpretation.

Didn’t our life begin with the act of love by a couple who sought spaces to give themselves to each other from skin to soul or vice versa?

Humanity demands acts; that’s the call of Pope Francis, who performs his mission aware of the complexity of universal reality. Rather than look for the Francis effect, we need to look closer at what he seeks and wants.

Far from being naïve, this Jesuit pope knows his objective and he proclaimed it: to generate “processes.” And he knows perfectly the equations of the socio-economic-political dynamics, which, while they knock at the door of the established powers, palpitate in the gutters of society in our increasingly reduced world.

The discarded ones are — like Jesus, the initiator of a grand process unfinished and difficult — the image of an inescapable reality, and the processes of transformation and change operate on realities that are in plain sight (when we want to see) and are not cold figures: just one of them is the whole of humanity.

They must be the actors in this “process,” not just its main beneficiaries (seen from an ideal perspective); they live in the sidewalks and corners of our streets, cities and villages.

That is why Francis shared a frugal table with them. He didn’t make speeches to them. His mere presence irradiated commitment. His magnetism or magic lies in the fact that he, all of him, is the integration of consistent thought and attitude.

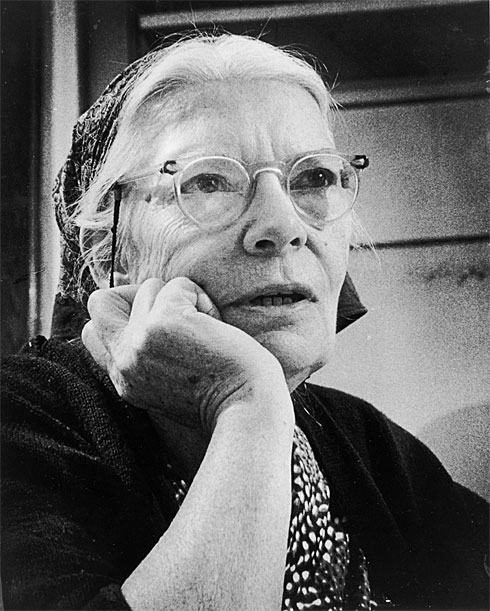

It was his way to say to them “I’m one of you. My parents went hungry and perhaps their roof was not big enough to shelter the children, so the family emigrated.” His “old man” was a laborer and possibly the reason why, during Francis’ address to Congress, he cited — among four greats in U.S. history — an exceptional woman: Dorothy Day.

Why and for what purpose did he name her, hidden in history as she is? Why did he cite a woman who once said, “If we’re not persecuted for our beliefs and life, there’s something wrong with us”?

Dorothy Day, a single mother, had an abortion, was a Catholic socialist, a radical pacifist, an advocate of women’s right to vote; she lived in one rented house after another and often had the stars for a ceiling; she founded The Catholic Worker, a newspaper that was an important voice of the labor movement.

She was arrested on several occasions, staged hunger strikes; moving consciences, she founded shelters where she fed the hungry, and was harshly criticized by the Catholic hierarchy of her time.

She walked in the gutter of society for her work in favor of small communities of socialist life and work (she was an anticapitalist) that are somehow reminiscent of the Jesuit efforts to create redoubts in Paraguay, a sort of Christian communitarianism.

And she stood on the sidewalk of the Catholic Church, where she was a fervent militant. But, because she was difficult and inadequate, the hierarchy of her time sidelined her. She was “discarded,” the Pope might have said.

Francis praises her, beside other great individuals, not only as the recognition of a life devoted to the service of others but also as an American who practiced a deep Christianity lived with intensity and committed to others.

Further, Francis cites her as an example of how to initiate processes, because, with the passing of years, several of the ideas and efforts of that fascinating and seductive woman have been adopted by the Catholic hierarchy in the United States.

She, Dorothy, can in a way summarize the thinking of Francis as the dynamics of an internal process that has begun in the bosom of the Catholic Church and also as the social and economic projection that the world community should adopt.

Francis’ reference was a call for all those “discarded” from the existing wonders to state their claims and act in the manner of that bride of all alienated people who was — and is — Dorothy Day.