Fed talk of raising interest rates is irresponsible

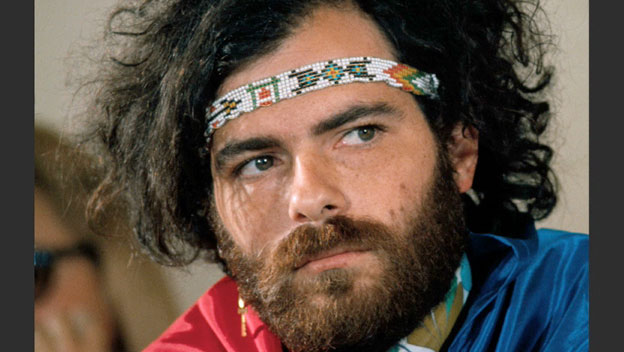

In his manifesto 45 years ago, “Do It!: Scenarios of the Revolution,” 1960s radical Jerry Rubin (in photo at top) described how his leftist Aunt Sadie would try to indoctrinate him as a child. “And as she ladled more chicken soup into my already overflowing bowl, she’d whisper into my ear, ‘The capitalists need unemployment to keep wages down.’”

Turns out she was right, if you substitute the word “want” for need. America’s largest corporations – even the ones who actually employ workers in the United States – can survive comfortably under full employment, as they did as recently as 2000, when unemployment was below 4 percent for the year.

But they much prefer the environment of stagnant real wages, as we have had for most of the past 35 years. This, in turn, requires a healthy supply of unemployed labor willing to work for less. Unfortunately their view generally finds sympathetic friends among the decision-makers at the Federal Reserve. Even more unfortunately, the Federal Reserve actually has the power to create unemployment for the direct purpose of keeping wages down, and that is what they do when they raise interest rates in the United States.

Economists know that when the Fed raises short-term interest rates, the purpose is to throw people out of work, by reducing spending in the economy, in order to put downward pressure on wages. The Fed and its supporters will say that this chain of events is necessary to keep inflation under control. At any moment – including the current one – that last piece of the argument, that inflation would otherwise get too high, can be debated. But if more people knew about what the Fed is actually doing, there would be more political resistance, and perhaps even public outrage.

This is especially true right now, with inflation running at nearly zero — 0.2 percent for the Consumer Price Index over the past year. The Fed’s preferred indicator of inflation, the personal consumption expenditures deflator, is at 1.2 percent (excluding food and energy). This is still quite a bit below the Fed’s own inflation target, which is 2 percent — and which many economists would argue is already too low of a target.

Yet the Fed’s number two, Vice President Stanley Fischer, indicated last week at the Fed’s annual retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, that the Fed is likely to stick to its plan to raise interest rates before the end of the year. This is despite falling commodity prices, the recent turmoil in financial markets and the weakness of the global economy.

But Fischer will not have the final word in the public debate. The Fed is finally being met with grassroots organizing intent on stopping it from creating unnecessary misery. A coalition of more than 100 organizations under the banner of “Fed Up” has been building pressure to stop the Fed from raising interest rates too soon. They held teach-ins and work-shops at the Fed’s retreat in Jackson Hole that included prominent economists such as Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz. One teach-in was entitled, “Do Black Lives Matter to the Fed,” reflecting among other inequalities that the unemployment rate for African-Americans is about twice the level of that for whites.

The fluctuations of stock market values may dominate the headlines of the business press, but being able to find a job is what matters most to most people. Furthermore, the unemployment rate greatly affects wage growth. For example, as the U.S. economy approached full employment in the second half of the 1990’s expansion, workers in the bottom half of the wage distribution saw wage increases that they had not seen in many years.

And yet the Fed almost blocked that employment and wage growth with a series of interest rate hikes beginning in early 1994 that doubled short-term interest rates from 3 to 6 percent within a year. Fortunately, then Fed Chair Alan Greenspan reversed course and began lowering rates in July 1995, apparently realizing that unemployment could fall further without provoking “unacceptable” rates of inflation; this reversal enabled another five years of growth. Now the Fed is threatening to put the current expansion at risk by raising interest rates as early as three weeks from now, or (much more likely) at their following meeting in December. Although U.S. unemployment is currently at 5.3 percent, we are still about three or four million jobs below where we should be, since many people have left the labor force since the Great Recession because they could not find jobs.

The ability of citizens to challenge the decision-making of central banks and hold them accountable is essential to any kind of meaningful democracy in the 21st century. The Federal Reserve makes what is arguably the most important economic decision for the vast majority of Americas: how many people will be involuntarily unemployed. Yet the conventional wisdom among economists and the business press is that this decision should be made by “independent” central banks. But “independent” does not mean independent from the influence of corporations and banks – it means independent from public accountability.

People are finally organizing to demand accountability from the Federal Reserve. This is a movement that is long overdue, and needs to spread throughout the world. The unemployment rate is too important to be left to the unelected friends of bankers and other special interests.