TPP is in trouble, thanks to public interest

The public debate over the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership has been a lot more robust and educational than the one that preceded the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement more than two decades ago. During that fight, then-Washington Post editorial page editor Meg Greenfield didn’t see a problemwith a six-to-one ratio of space for pro- vs. anti-NAFTA editorials. “On this rare occasion when columnists of the left, right, and middle are all in agreement … I don’t believe it is right to create an artificial balance where none exists.”

Today there are more economists in the news debunking the arguments put forth to promote the TPP, and this has contributed to the collapse of some of these talking points.

This week, economists Dean Baker and Paul Krugman warn that people should be suspicious of any agreement that leads its proponents to lie and distort so much in order to sell it. They called attention to President Barack Obama’s former Chief of Staff William M. Daley, who made the ridiculous claim in a New York Times op-ed that it is “because our products face very high barriers to entry overseas in the form of tariffs, quotas and outright discrimination” that the U.S. ranks 39th of the 40 largest economies in exports as a share of GDP. As Baker and Krugman pointed out, it is actually because the U.S. is a very large economy, and therefore the domestic market is sufficient for many U.S. companies.

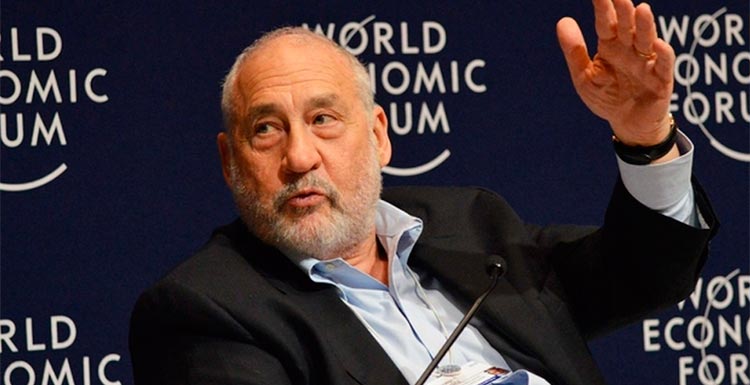

This is just one of the many arguments in TPP’s favor that cannot pass the smell test. Take the Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanism, which enables businesses to sue governments and can force them to overrule their laws, even the decisions of their highest courts, or pay hefty fines. Proponents’ alleged rationale for including this provision is to protect foreign investors in countries where the rule of law is weak. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate economist like Krugman, pointedly asks why it is included in the proposed trade agreement with Europe (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership). Let me offer you a hint: It’s not because Germany and France are likely to expropriate factories owned by foreign investors, or that their judicial systems are weak on investors’ rights.

Public interest groups that care about the little things in life — you know, the environment, public health and safety, financial regulation — have railed against this corporate power grab. Not to worry, says the White House: The U.S. is party to dozens of agreements that contain ISDS, and there have been only 13 judgements against the U.S. over the past three decades.

Now comes economist Jeffrey Sachs, who has long been a supporter of expanding international trade, with some inconvenient facts: “In 1995, only a handful of ISDS cases had been filed; as of the end of 2014, there had been more than 600 known claims (because most arbitration can be conducted in secrecy, there may have been many more claims).” So, the past is no guide to the future damage that these pro-corporate tribunals may bring. Another TPP defense flunks the smell test.

Economists have helped at least the more open-minded among journalists to discover a few things that in prior years got lost in all the ideology and hand-waving about “free trade.” For example, that the TPP is not mostly about trade, and even less about free trade, but about establishing a set of rules that benefit large corporations: Consumer losses to powerful protectionists buoyed by TPP such as big pharmaceutical companies can easily wipe out the miniscule gains from trade — and yes, they are miniscule. The impact of trade liberalization on wage inequalitycan also negate any gains from trade for most employees.

On the defensive much more than Bill Clinton was, President Obama attacked Sen. Elizabeth Warren for suggesting that the TPP could be used to undercut financial regulatory measures approved in the wake of the Great Recession. Just four days later, Canada’s Minister of Finance Joe Oliver said at a securities conference in New York that the Volcker rule, a key provision of the Dodd-Frank financial reform law, violates NAFTA.

Having lost all the economic and public-interest arguments, TPP proponents have resorted to one last-ditch argument. “If we don’t write the rules, China will write the rules,” President Obama warns, only to be parroted by any number of “patriotic” pundits and politicians.

The key word here, of course, is “we.” Does “we” refer to the corporate and industry association representatives that are 90 percent of the official trade advisers with access to the negotiated text of the TPP? If so, it’s not so clear that we the people should be so worried about China. Should we the people care if China expands its influence in Asia, which is pretty much inevitable because its economy is already bigger than that of the U.S., is growing several times faster, and happens to be located in that part of the world? Are we the people going to be worse off if Chinese companies increase their access to cheap labor in Vietnam or Bangladesh faster than U.S. corporations do?

Another smell test: Why is it that the Obama administration is expected to give up on the TPP if it can’t get what it needs from Congress before the presidential race heats up? Because many and perhaps most Americans have probably never heard of the TPP, but many will if it becomes an issue in the presidential race. This admission that public awareness is deadly to the TPP is not very flattering to the proposed agreement — which, by the way, we aren’t even allowed to see.

Unfortunately there is one thing that hasn’t gotten better since Bill Clinton’s fight for NAFTA 20 years ago: vote-buying in Congress. In 1993 this took the form of not only campaign contributions but also billions of federal dollars the Clinton administration steered to the districts of members of Congress whose votes they needed. Today, the Senate has already been bought; now we will see whether the grassroots lobbying of public interest groups and ordinary citizens can win in the Congress what it has won in the public debate.