Syriza’s win is the beginning of the end for the Eurozone’s long nightmare

Everyone seems to agree that Syriza’s big victory in Greece is a milestone for Europe, which has been plagued by mass unemployment and a failure to really recover from the financial crisis and world recession of 2008-09. But what kind of a milestone will it be? We can get some ideas from focusing on a few key issues, especially economic policy, which remain surrounded by much confusion in the public debate.

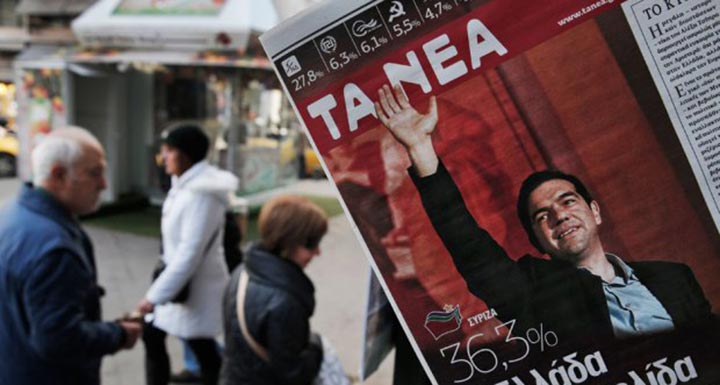

Alexis Tsipras himself, the charismatic 40-year old leader of Syriza who has become the country’s youngest prime minister in 150 years, declared on Sunday that “Democracy will return to Greece.” This was mostly overlooked as mere political rhetoric, but it was actually a concise political statement that goes to the core of not only Greece’s but the eurozone’s main problem. All we need to do is compare the recovery of the United States – which was the epicenter of the earthquake that shook the world economy in 2008 and 2009 – and that of Europe, to see what a difference democracy makes.

Even the very limited-accountability, Wall Street-dominated, mass-disenfranchisement form of democracy that prevails in the U.S. proved vastly superior to the economic autocracy of the eurozone. Although the Great Recession was our worst downturn since the Great Depression, it lasted just 18 months before the recovery began. The eurozone had a recession of similar length, but then lapsed into another one in 2011 and has only recently begun a sluggish recovery. As a result, unemployment in the region stands at 11.5 percent, more than twice that of the United States (5.6 percent).

The difference is due to economic policy: macroeconomic (fiscal and monetary) policy in particular. We got a modest stimulus; they got budget tightening in the weakest economies of the eurozone. We got the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) beginning in 2008; the European Central Bank (ECB) did not announce QE until last week. The people making the macroeconomic policy decisions in the U.S. had at least some – to varying degrees – accountability to an electorate. But in the eurozone, more than 20 governments fell and yet for years the destructive policies decided by the unelected European authorities – the European Commission, the ECB, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – marched forward. Perhaps nowhere in the eurozone have these policies failed more miserably than in Greece.

The election of Syriza is the biggest breakthrough yet in the painfully slow-motion process of the eurozone populations reclaiming their democracy on fundamental economic policy issues, which had been delegated to unelected European officials. François Hollande was elected on an anti-austerity backlash in 2012, but he didn’t deliver. Now it is Tsipras’ turn.

Syriza has certain advantages due to the passage of time. First, the fiscal austerity that Greece signed on to is pretty much done. The IMF’s “cyclically adjusted primary government budget balance” is a simple measure to look at how much the government is tightening its budget during a year. This adjusts the budget deficit or surplus for fluctuations due to the business cycle, and excludes interest rates, in order to isolate the impact of government policy changes on spending and revenues. If we look at Greece, the tightening of this balance – i.e. the “fiscal austerity” – in 2014 was just 0.3 percent of GDP, from 5.7 to 6.0 percent of GDP. In the three years prior, the adjustment had been 3.2 percent of GDP (2012-13), 3.8 percent of GDP (2011-12), and 5 percent of GDP (2010-11).

This explains why the economy finally began to grow, at 0.6 percent of GDP, in 2014. It was not because the austerity “worked,” as some now disingenuously claim, but because it basically came to an end.

Greece has also completed the economic adjustment that its punishers have put forth as a main object of austerity. Its current account (mostly trade) is in surplus – imports have fallen by 36 percent since 2008, one of the largest adjustments in the world. Its primary (excluding interest) government budget balance is also in surplus. No one can credibly argue that Greece is living beyond its means.

But the recovery is still too weak, slow, and fragile to take the country out of the mass unemployment that the European authorities have unnecessarily inflicted on Greece. The IMF projects nearly 16 percent unemployment in 2018 and almost all of its projections since 2010 have been decidedly overly-optimistic. Unemployment is currently at 25.8 percent, and nearly double that for youth.

To bring the country to full or even reasonable levels of employment, the new government will have to enact a fiscal stimulus. Tsipras also proposes to roll back some of the regressive changes implemented during the past few years, such as restoring the minimum wage cuts and lost collective bargaining rights. He also wants to re-negotiate the country’s oversized debt, which is currently over 170 percent of GDP. It was just 115 percent of GDP in May 2010 when the first IMF agreement was signed and many of us warned that austerity was the road to hell.

The people have spoken, a government has been formed, and now the ball is in the court of the European authorities. They will have to decide whether they won enough, in terms of restructuring the eurozone economies to chip away at the welfare state, reduce labor’s bargaining power, cut health care spending (by 40 percent in Greece), and construct a more unequal society. It is a dilemma for them, because if they give in to Syriza, Spain could be next. The left Podemos party, which rose from its founding to lead the polls in just the past year with a program similar to Syriza’s, could benefit greatly from a successful Syriza administration. Spain’s economy is more than six times the size of Greece’s.

On the other hand, if the European authorities refuse to bargain with Syriza, there is a risk that Greece ends up outside of the euro. Contrary to popular belief, the European authorities do not fear a Greek exit because it could cause a serious financial crisis of the euro. Like the Federal Reserve of the United States, the ECB can create money, and has all the firepower it needs in order to make sure that a Greek exit would not cause serious damage to the eurozone financial system. It demonstrated that in July 2012 when ECB President Mario Draghi put an end to two years of financial crisis, and doubts about the survival of the euro itself, by merely stating he would do “whatever it takes” to defend the euro.

The real fear is Greece might leave and – after an initial crisis and capital fight –recover much more quickly than the rest of the eurozone, prompting other governments to also want to leave the euro. Bluff and bluster fill the financial press at the moment, but the smarter people in Brussels and Frankfurt understand this reality, and will want to make some concessions to the new government in Greece. Either way, this is the beginning of the end of the eurozone’s long nightmare.

* Mark Weisbrot is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in Washington, D.C. He is also president of Just Foreign Policy.

(From the: CPR)