The U.S. State Department responds to my four-year-old FoIA request… sort of

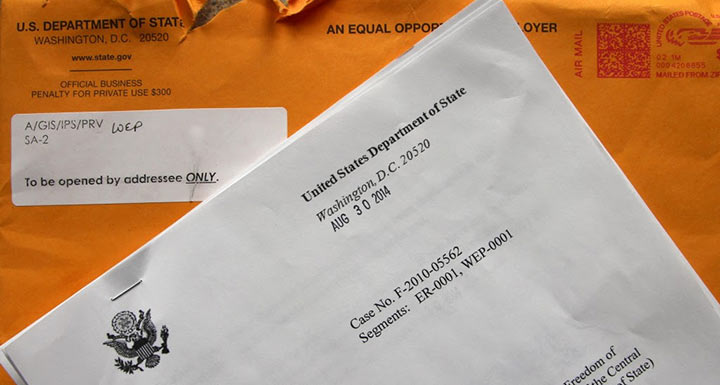

When I arrived back in Halifax on September 14, 2014 from giving talks in Washington about the case of the Cuban Five, there was an envelope waiting for me. It was from the “U.S. Department of State” and there was a sticker on the manila envelope that warned: “To be opened by addressee ONLY.

The envelope contained the State Department’s response to an almost forgotten Freedom of Information Act request I’d filed four years earlier, on September 9, 2010 (not “2004” as the accompanying letter declared; even the State Department — one hopes — doesn’t take that long to respond to a simple request for information).

The envelope contained the State Department’s response to an almost forgotten Freedom of Information Act request I’d filed four years earlier, on September 9, 2010 (not “2004” as the accompanying letter declared; even the State Department — one hopes — doesn’t take that long to respond to a simple request for information).

Since I’d filed the original request — Case #201005562 — four years ago, I’d periodically emailed the Department for progress reports. On July 12, 2013, a Chris Barnes responded: “I checked the electronic notes on this case. The case is still open. The case notes indicate documents from a search are currently under review. Each case is different and the time it takes depends on the complexity of information requested and the time it takes to review the material.”

Given the time it was taking, I began to hope State Department minions, in their diligent search among musty basement documents and back room records from more than 15 years before, must have struck the motherlode and were now busily assembling it for me.

So when the Department wrote again on April 1, 2013 — humor unintentional, I’m sure — to “determine if you are still interested” in the files, I immediately responded that I was. “Can you tell me when I can expect a response?”

No none did — until the envelope arrived in the mail.

The envelope contained 10 pages, three of them the cover letter and boilerplate on Appeals Procedures, on the off chance I wanted to wait another four years for a further answer. Of the seven remaining pages, there were three documents: “We have determined that two may be released in full and one may be released with excisions.[1] All released material is enclosed.”

The good news was that, “since fewer than 100 pages have been duplicated in this case, your request has been processed without charge to you.” Well, thanks for that.

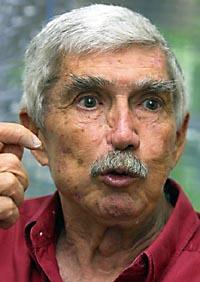

So what are these documents that took the U.S. government four long years to uncover and vet? [2] The three documents — two cables and a diplomatic note — all relate to the 1997 Havana hotel bombing campaign, which was masterminded by Cuban exile militant Luis Posada Carriles and financed by members of the powerful Cuban American National Foundation. (Posada acknowledged both those assertions in a 1998 New York Times interview.)

There is nothing especially new in any of the documents, except the claim[3] the US Government asked the Cubans in diplomatic notes on at least five occasions that summer (July 13, August 7 and 21, and September 5 and 11) to “furnish all information it may have in its possession that concretely links U.S. persons or organizations to any of the explosions.”

The first document is an unclassified cable from the US Interest Section in Havana to the State Department, the White House and more than a dozen American embassies. The subject heading: “FOREIGN MINISTER SAYS U.S. RESPONSIBLE FOR CONSEQUENCES OF RECENT HAVANA BOMBINGS.” Reference: “KOZAK/JACOBS TELCON AUGUST 21.” (In government-speak, a telcon is a teleconference, this one presumably between Michael Kozak, the then-head of the US Interest Section and someone named Jacobs, perhaps Morris E. “Bud” Jacobs, who “held several public diplomacy and policy positions for the Department of State and the U.S. Information Agency” at the time.)

The note focused on statements Cuban Foreign Minister Robert Robaina had made in Granma, the Cuban government daily newspaper, in which he said the United States government had “supported the recent explosions at Havana hotels and would be responsible for whatever consequences that arise… Robaina said that over the years the [Government of Cuba] has given the [U.S. Government] sufficient proof to convict individuals of such crimes, but that US courts prefer to listen to politicized arguments of the defense.”

The cable quoted from its own diplomatic note in response: “Clearly only the Cuban side can be responsible for the consequences of its failure to provide relevant information and evidence.”

In a later diplomatic note referenced in the second cable, the U.S. again urges the Cubans to share information and promises: “If the Government of the Republic of Cuba furnishes the necessary information and evidence of US-based criminal wrongdoing, the United States Government will take the appropriate law enforcement steps.”

The reality is that they did not.

Fast forward to June 1998 after Cuban State Security finally did share the evidence it had gathered with the FBI during three days of meetings in Havana. The FBI promised to investigate and report back to the Cubans. Instead, three months later, they arrested not the terrorist plotters but the Cuban intelligence agents who’d helped uncover their plots.

Luis Posada Carriles? He still walks the streets of Miami, a free man.[4]

***

[1] The “excision” appears — or actually doesn’t appear — in the Summary section of a cable about a September 19thdiplomatic note from the US Interests Section to the Cuban Government. The exemption claimed is for “information specifically authorized by an executive order to be kept secret in the interest of national security of foreign policy.”

[2]To be fair, these documents are at least more to the point than the 400 pages of easily publicly available newspaper clippings the Federal Bureau of Investigation sent me in 2012 after a similar multi-year wait for “relevant” documents concerning the Bureau’s involvement in a series of June 1998 meetings in Havana between the FBI and Cuban State Security concerning terrorist attacks against Cuba.

[3] Interestingly, in their exhaustive search for the material I’d asked for, the State Department apparently didn’t find the text of any of them, except the September 5 and 19 notes. At least they didn’t include them in the material they sent me.

[4] The US government did belatedly acknowledge Posada’s role in plotting the Havana hotel bombings. They didn’t charge him with actually plotting those terrorist attacks, of course, but, in an Orwellian twist, with lying on an immigration form about his role in planning the bombings! During his trial in 2010, prosecutors introduced the same documents the Cubans had turned over to them 13 years earlier. And so it goes.

* Stephen Kimber teaches journalism at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Canada, and is the author of “What Lies Across the Water: The Real Story of the Cuban Five.”

(From the: Stephen Kimber website)