Venezuela: between negotiations and harassment

HAVANA — Still under the effects of Hurricane Irma, the Dominican Republic this week hosted conversations between the Venezuelan government and its opposition.

Although many people doubt that forces so polarized can reach significant agreement, it is evident that the talks reflect the Venezuelan people’s support for the call to a Constituent Assembly. That support neutralized a climate of confrontation that reached extreme levels of violence in the streets, as well as the international harassment against the Venezuelan government. Even Donald Trump now talks about supporting the dialogue.

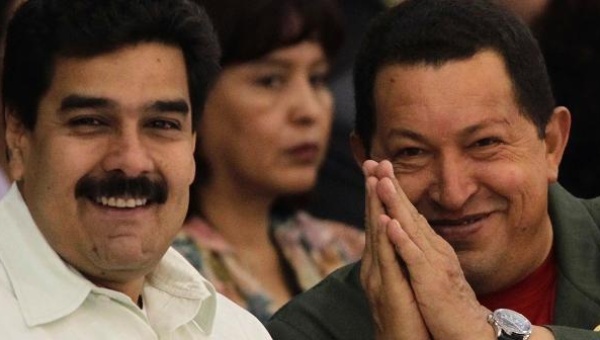

Hugo Chávez’s victory at the polls in 1998 marked the rise of a Latin American resistance movement to the neoliberal model installed in the region by international capital, the multinational corporations and the native oligarchies sheltered by the policies of the United States.

Its influx rapidly affected much of the region and fostered what became known as a “progressive cycle” that posited political and social transformations inside nations and obstacles to the crystalization of the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas (ALCA) Also, greater efforts than ever were made toward the integration of Latin America and the Caribbean, with results that affected U.S. hegemony in the region.

This explains why the administrations of Bush, Obama and now Trump articulated some very aggressive policies against the Bolivarian Revolution, which were joined not only by the opposition sectors at home but also the Latin American right as a whole, especially after the defeats of the popular movements in Argentina and Brazil.

Both the U.S. liberal and conservative sectors supported that offensive but also the Cuban-American far right, which stood out in its creation and organization. For that reason, Miami once again became the political capital of such groups.

Notorious for her aggressiveness against any Latin American nationalist process, Representative Ileana Ros-Lehtinen — as chairwoman of the House Foreign Relations Committee (2011-2013) — became the cementing core of the Latin American right-wingers, to whom she made available the U.S. Capitol itself to carry out their activities.

Now that role has been passed to Senator Marco Rubio, a generator of the more bellicose Trump policies toward the region.

It is worth noting that this is not just a movement inspired in ideological fundamentalism and is not exclusively an imperialist policy interested in tilting the regional balance to the right.

To the Latin American right, the existence of the current revolutionary government in Venezuela is a problem of domestic policy, inasmuch as this influence can determine its own existence as the dominant class.

Therein lies the stubbornness of the failed attempts to condemn Venezuela in the Organization of American States, compromising even more the prestige of that organization and the pan-American system in general.

The development of a revolutionary process in a country as rich as Venezuela constitutes an extraordinary impediment to sustain the neoliberal model in Latin America and the Caribbean. It is also a bad example for the dominant sectors of the developed capitalist countries, which explains why all of them have joined the campaign against Chavism.

When the Spanish government demonizes the Venezuelan government, it’s aiming its guns toward the vernacular left, represented by the Podemos Party.

Escalating the tension created by Obama’s directive to declare Venezuela a threat to the national security of the United States, Trump floated the possibility of military intervention against that country. Even Colombia’s Santos reacted in horror, aware that the forces pushing such possibility don’t fear the chaos that it would provoke.

On the contrary, encouraged by the huge profit that results from those interventions and confident of their repressive capacity to “reconstruct” the countries they previously destroyed, some sectors of the U.S. oligarchy and their native allies find this state of affairs to be functional, in terms of eventually imposing the most anti-popular policies.

That has been the case since “the Chicago boys” found in Pinochet’s dictatorship an ideal stage to impose “undistorted capitalism” in Latin America.

Those are the alternatives being decided in Venezuela and what’s really important at the time to take a stance. Clearly, Chavism is not a perfect form of governance; it has been unable to shed the corruption and inefficacy that are endemic in Venezuelan politics and has been powerless to transform a rentier government that has suffered the collapse of the oil market.

However, it has done more for the Venezuelan people than any other previous government, which has allowed it to overcome what seemed like a death foretold.

In that capacity for resistance lie the exceptionality of Venezuela’s political process and the source of its legitimacy.

*****

Below is part of the speech given by President Trump at the United Nations on Tuesday (Sept. 19) where he stated that “the problem in Venezuela is not that socialism has been poorly implemented, but that socialism has been faithfully implemented.”