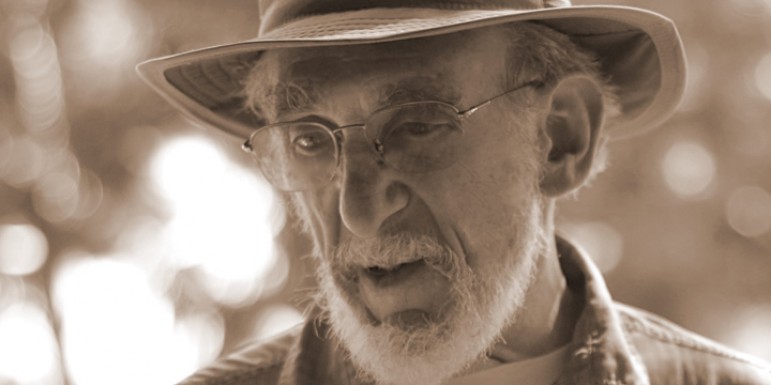

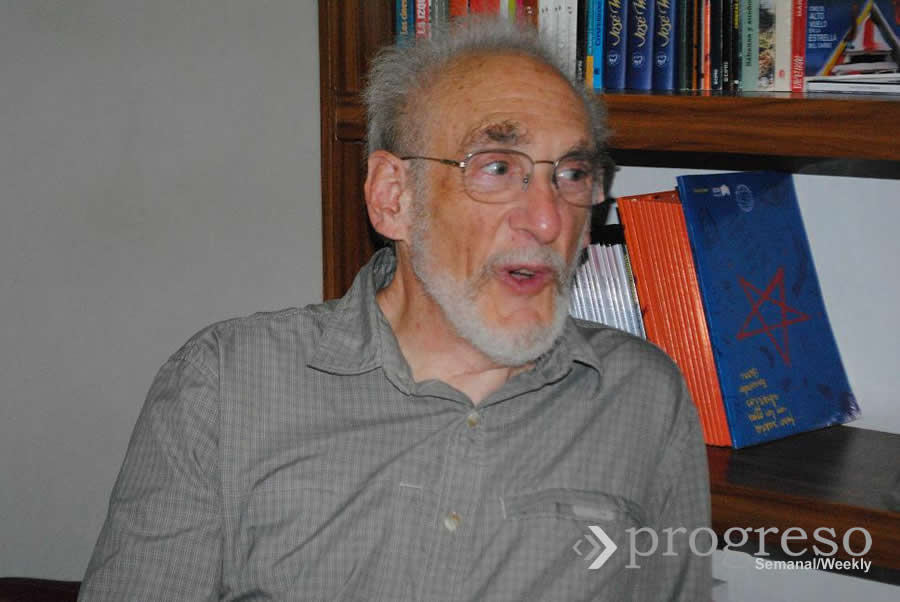

Mark Berger: A history in sound

Four Oscars and films like The Godfather II, Apocalypse Now, Amadeus, and The English Patient are part of the reputation that precedes Mark Berger, the sound engineer born in southern California.

Because of his age (71), or maybe because of his inborn talent, it is easy for Berger to turn his entire universe into sound tracks. That’s how I perceived him when he visited Cuba at the invitation of the International School of Cinema and TV at San Antonio de los Baños.

Our conversation began with the era when television still did not reach his home, on one of the many nights when he went to bed to find, instead of sleep, an access door to all the imaginable worlds.

All he had to do was tune his ear and, like someone who guesses the combination of a safe lock, turn the dial of his radio.

“My life story began with that passion,” he says. “I always enjoyed more listening than seeing. Radio allows you to form images that respond only to sounds, and that ability is essential in my profession.”

They say your formation as a mixer [sound designer] was quite random.

I was studying experimental psychology at the University of California at Berkeley. I always say that my job was to open the brains of lab mice.

By chance, I took part in the recording of some documentaries for radio about the efforts against the war in Vietnam. The boyfriend of the woman with whom I made those recordings was a film editor.

Through him, I got a job in the South dealing with the civil rights of workers. We went to New Orleans and spent about nine months there, making the film. Later, we showed it in New York, looking for funds for all those disadvantaged people.

Upon returning to the university, I realized that that experience was more interesting to me than academic studies. Suddenly, I found a job recording sound for a documentary on the programs of the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID].

I visited 11 countries in seven days, recording and filming. What could be better?

How did you get your first feature film?

How did you get your first feature film?

I was showing a film about California at the home of [director/producer] Francis Ford Coppola. A fellow was looking at me from the door, and after the showing surprised me by saying, “I have a job that you might be interested in helping me with.” The man was Walter Murch, Coppola’s editor. The project was “The Conversation.”

Of course, I accepted. But the movie was postponed several times and when it was finally filmed, I was here, in Cuba.

I wanted to ask you about that.

Yes, that time I was working on an interview with Fidel Castro. We traveled throughout the island and interviewed him over three nights. The team included Frank Markovich, who was press secretary for [Senator] Ted Kennedy, brother of the U.S. president, and filmmaker Saul Landau.

Also at the time I met Jerónimo Labrada, current director of the International School of Cinema and TV at San Antonio de los Baños. He was recording sound for the Spanish version while I did it for the English version.

This experience had to do with your participation in ‘The Godfather II.’

I think that I would have participated anyway, because of what I told you earlier, but, yes, it did have a bearing. When I returned, Walter asked me: “You’ve just come back from Cuba, right?” I answered yes. “And you have sound that you recorded there?” “Yes.” “Then I want you to cut all the sequences on the island for ‘Godfather II.'” And that was my first job in a feature film.

Your work relies more on simplicity than grandiloquence. How did you assume that modality?

Your work relies more on simplicity than grandiloquence. How did you assume that modality?

I worked at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, which made more dramas than adventure or action films. Maybe because of that, I earned the reputation of someone who gives much importance to the dialogue, to the actors’ emotions. As years went by, that inclination sharpened until it became a hallmark.

I must tell you that, out of the 170 movies in which I’ve worked, only three were done in Los Angeles. I’ve done many documentaries, low-budget films and some personal ones.

I like to travel and teach; I’ve been in many cities and countries. For the past 15 years, I’ve conducted a course at Berkeley on the meaning of sound in films. I think it’s my duty to transmit the knowledge I’ve accumulated in my career.

At 71, are you satisfied with your achievements?

I am very pleased. I’ve had much recognition from the public and filmmaking professionals. I continue to mix one or two movies per year, but I look for what appeals most to me.

After all, the movie itself is not more significant than the people you work with. That’s what interests me the most: the exchange, the development of ideas during a mix.

More than 170 movies, four Oscars — what has been the key to your success?

To be in the right place at the right time, with the right knowledge and a lot of effort. I always take advantage of the opportunities that are offered to me. I never said ‘no, I can’t do that.’ I confess that luck has played an important part, but luck helps only if you have knowledge and work hard. I also pay much attention to the smallest details as well as to the whole story.

Do you go to the cinema to see and hear your work?

No, sound is heard best in the mixing studio. All other spaces have variations that affect the original soundtrack. There’s always problems.

What is filmgoer Mark Berger like?

My friends don’t like to accompany me to the movies. When something goes wrong, I stand up and go to the projection room if necessary. Sometimes the managers have told me, “We’ll refund you the money if you don’t like it, but don’t bother us anymore.”

By the time I come back to my seat, my friends — watching my performance — have missed half the movie.