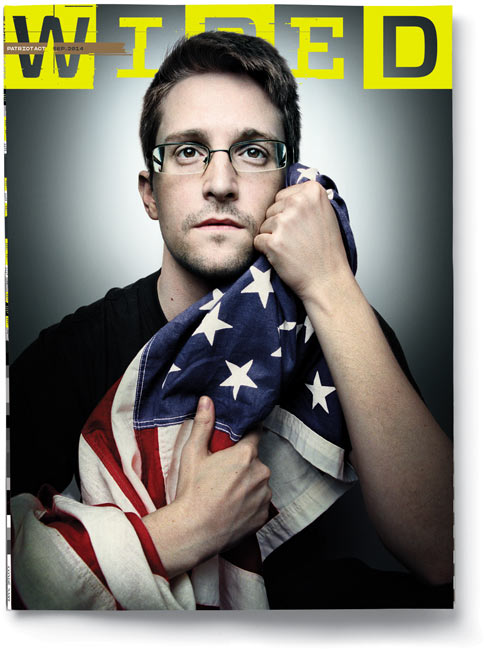

The most wanted man in the world

The message arrives on my “clean machine,” a MacBook Air loaded only with a sophisticated encryption package. “Change in plans,” my contact says. “Be in the lobby of the Hotel ______ by 1 pm. Bring a book and wait for ES to find you.” ES is Edward Snowden, the most wanted man in the world. For almost nine months, I have been trying to set up an interview with him—traveling to Berlin, Rio de Janeiro twice, and New York multiple times to talk with the handful of his confidants who can arrange a meeting. Among other things, I want to answer a burning question: What drove Snowden to leak hundreds of thousands of top-secret documents, revelations that have laid bare the vast scope of the government’s domestic surveillance programs? In May I received an email from his lawyer, ACLU attorney Ben Wizner, confirming that Snowden would meet me in Moscow and let me hang out and chat with him for what turned out to be three solid days over several weeks. It is the most time that any journalist has been allowed to spend with him since he arrived in Russia in June 2013. But the finer details of the rendezvous remain shrouded in mystery. I landed in Moscow without knowing precisely where or when Snowden and I would actually meet. Now, at last, the details are set.

I am staying at the Hotel Metropol, a whimsical sand-colored monument to pre-revolutionary art nouveau. Built during the time of Czar Nicholas II, it later became the Second House of the Soviets after the Bolsheviks took over in 1917. In the restaurant, Lenin would harangue his followers in a greatcoat and Kirza high boots. Now his image adorns a large plaque on the exterior of the hotel, appropriately facing away from the symbols of the new Russia on the next block—Bentley and Ferrari dealerships and luxury jewelers like Harry Winston and Chopard.

I am staying at the Hotel Metropol, a whimsical sand-colored monument to pre-revolutionary art nouveau. Built during the time of Czar Nicholas II, it later became the Second House of the Soviets after the Bolsheviks took over in 1917. In the restaurant, Lenin would harangue his followers in a greatcoat and Kirza high boots. Now his image adorns a large plaque on the exterior of the hotel, appropriately facing away from the symbols of the new Russia on the next block—Bentley and Ferrari dealerships and luxury jewelers like Harry Winston and Chopard.

I’ve had several occasions to stay at the Metropol during my three decades as an investigative journalist. I stayed here 20 years ago when I interviewed Victor Cherkashin, the senior KGB officer who oversaw American spies such as Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen. And I stayed here again in 1995, during the Russian war in Chechnya, when I met with Yuri Modin, the Soviet agent who ran Britain’s notorious Cambridge Five spy ring. When Snowden fled to Russia after stealing the largest cache of secrets in American history, some in Washington accused him of being another link in this chain of Russian agents. But as far as I can tell, it is a charge with no valid evidence.

I confess to feeling some kinship with Snowden. Like him, I was assigned to a National Security Agency unit in Hawaii—in my case, as part of three years of active duty in the Navy during the Vietnam War. Then, as a reservist in law school, I blew the whistle on the NSA when I stumbled across a program that involved illegally eavesdropping on US citizens. I testified about the program in a closed hearing before the Church Committee, the congressional investigation that led to sweeping reforms of US intelligence abuses in the 1970s. Finally, after graduation, I decided to write the first book about the NSA. At several points I was threatened with prosecution under the Espionage Act, the same 1917 law under which Snowden is charged (in my case those threats had no basis and were never carried out). Since then I have written two more books about the NSA, as well as numerous magazine articles (including two previous cover stories about the NSA for WIRED), book reviews, op-eds, and documentaries.

But in all my work, I’ve never run across anyone quite like Snowden. He is a uniquely postmodern breed of whistle-blower. Physically, very few people have seen him since he disappeared into Moscow’s airport complex last June. But he has nevertheless maintained a presence on the world stage—not only as a man without a country but as a man without a body. When being interviewed at the South by Southwest conference or receiving humanitarian awards, his disembodied image smiles down from jumbotron screens. For an interview at the TED conference in March, he went a step further—a small screen bearing a live image of his face was placed on two leg-like poles attached vertically to remotely controlled wheels, giving him the ability to “walk” around the event, talk to people, and even pose for selfies with them. The spectacle suggests a sort of Big Brother in reverse: Orwell’s Winston Smith, the low-ranking party functionary, suddenly dominating telescreens throughout Oceania with messages promoting encryption and denouncing encroachments on privacy.

Of course, Snowden is still very cautious about arranging face-to-face meetings, and I am reminded why when, preparing for our interview, I read a recent Washington Post report. The story, by Greg Miller, recounts daily meetings with senior officials from the FBI, CIA, and State Department, all desperately trying to come up with ways to capture Snowden. One official told Miller: “We were hoping he was going to be stupid enough to get on some kind of airplane, and then have an ally say: ‘You’re in our airspace. Land.’ ” He wasn’t. And since he disappeared into Russia, the US seems to have lost all trace of him.

I do my best to avoid being followed as I head to the designated hotel for the interview, one that is a bit out of the way and attracts few Western visitors. I take a seat in the lobby facing the front door and open the book I was instructed to bring. Just past one, Snowden walks by, dressed in dark jeans and a brown sport coat and carrying a large black backpack over his right shoulder. He doesn’t see me until I stand up and walk beside him. “Where were you?” he asks. “I missed you.” I point to my seat. “And you were with the CIA?” I tease. He laughs.

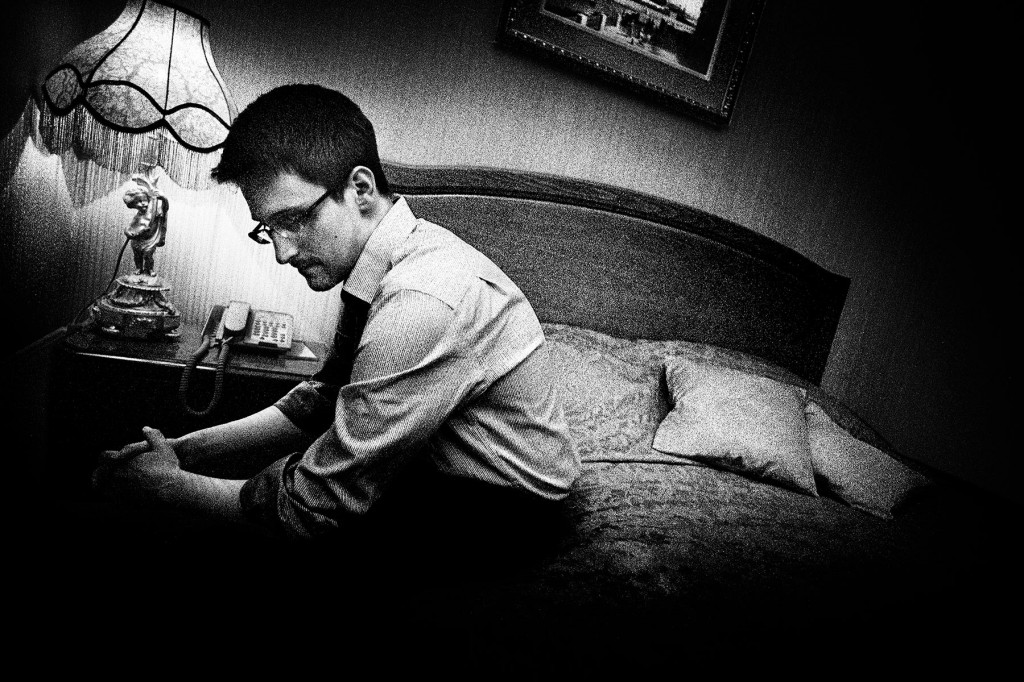

Snowden is about to say something as we enter the elevator, but at the last moment a woman jumps in so we silently listen to the bossa nova classic “Desafinado” as we ride to an upper floor. When we emerge, he points out a window that overlooks the modern Moscow skyline, glimmering skyscrapers that now overshadow the seven baroque and gothic towers the locals call Stalinskie Vysotki, or “Stalin’s high-rises.” He has been in Russia for more than a year now. He shops at a local grocery store where no one recognizes him, and he has picked up some of the language. He has learned to live modestly in an expensive city that is cleaner than New York and more sophisticated than Washington. In August, Snowden’s temporary asylum was set to expire. (On August 7, the government announced that he’d been granted a permit allowing him to stay three more years.)

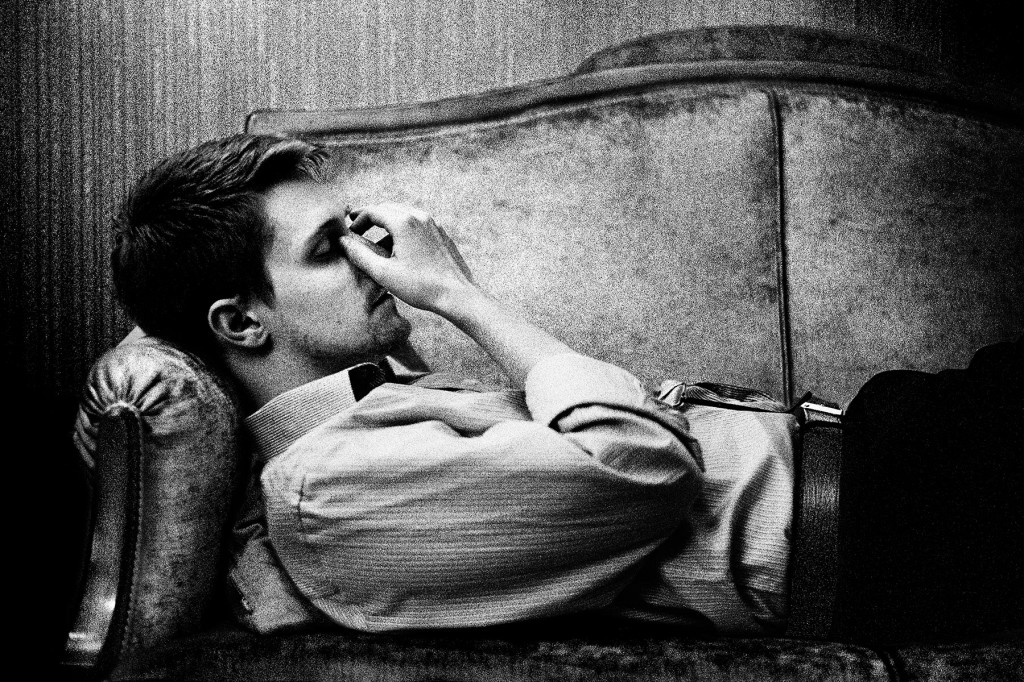

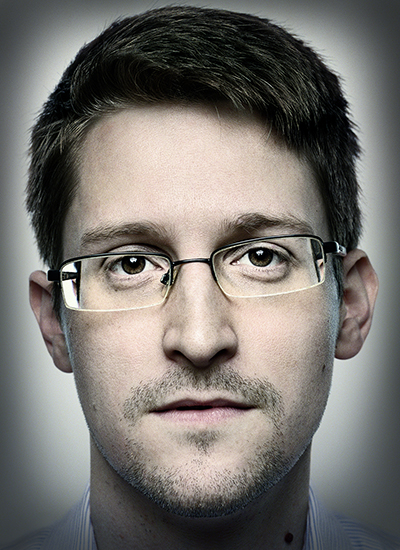

Entering the room he has booked for our interview, he throws his backpack on the bed alongside his baseball cap and a pair of dark sunglasses. He looks thin, almost gaunt, with a narrow face and a faint shadow of a goatee, as if he had just started growing it yesterday. He has on his trademark Burberry eyeglasses, semi-rimless with rectangular lenses. His pale blue shirt seems to be at least a size too big, his wide belt is pulled tight, and he is wearing a pair of black square-toed Calvin Klein loafers. Overall, he has the look of an earnest first-year grad student.

Snowden is careful about what’s known in the intelligence world as operational security. As we sit down, he removes the battery from his cell phone. I left my iPhone back at my hotel. Snowden’s handlers repeatedly warned me that, even switched off, a cell phone can easily be turned into an NSA microphone. Knowledge of the agency’s tricks is one of the ways that Snowden has managed to stay free. Another is by avoiding areas frequented by Americans and other Westerners. Nevertheless, when he’s out in public at, say, a computer store, Russians occasionally recognize him. “Shh,” Snowden tells them, smiling, putting a finger to his lips.

Espite being the subject of a worldwide manhunt, Snowden seems relaxed and upbeat as we drink Cokes and tear away at a giant room-service pepperoni pizza. His 31st birthday is a few days away. Snowden still holds out hope that he will someday be allowed to return to the US. “I told the government I’d volunteer for prison, as long as it served the right purpose,” he says. “I care more about the country than what happens to me. But we can’t allow the law to become a political weapon or agree to scare people away from standing up for their rights, no matter how good the deal. I’m not going to be part of that.”

Meanwhile, Snowden will continue to haunt the US, the unpredictable impact of his actions resonating at home and around the world. The documents themselves, however, are out of his control. Snowden no longer has access to them; he says he didn’t bring them with him to Russia. Copies are now in the hands of several news organizations, including: First Look Media, set up by journalist Glenn Greenwald and American documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras, the two original recipients of the documents; The Guardian newspaper, which also received copies before the British government pressured it into transferring physical custody (but not ownership) to The New York Times; and Barton Gellman, a writer for The Washington Post. It’s highly unlikely that the current custodians will ever return the documents to the NSA.

That has left US officials in something like a state of impotent expectation, waiting for the next round of revelations, the next diplomatic upheaval, a fresh dose of humiliation. Snowden tells me it doesn’t have to be like this. He says that he actually intended the government to have a good idea about what exactly he stole. Before he made off with the documents, he tried to leave a trail of digital bread crumbs so investigators could determine which documents he copied and took and which he just “touched.” That way, he hoped, the agency would see that his motive was whistle-blowing and not spying for a foreign government. It would also give the government time to prepare for leaks in the future, allowing it to change code words, revise operational plans, and take other steps to mitigate damage. But he believes the NSA’s audit missed those clues and simply reported the total number of documents he touched—1.7 million. (Snowden says he actually took far fewer.) “I figured they would have a hard time,” he says. “I didn’t figure they would be completely incapable.”

Asked to comment on Snowden’s claims, NSA spokesperson Vanee Vines would say only, “If Mr. Snowden wants to discuss his activities, that conversation should be held with the US Department of Justice. He needs to return to the United States to face the charges against him.”

Snowden speculates that the government fears that the documents contain material that’s deeply damaging—secrets the custodians have yet to find. “I think they think there’s a smoking gun in there that would be the death of them all politically,” Snowden says. “The fact that the government’s investigation failed—that they don’t know what was taken and that they keep throwing out these ridiculous huge numbers—implies to me that somewhere in their damage assessment they must have seen something that was like, ‘Holy shit.’ And they think it’s still out there.”

Yet it is very likely that no one knows precisely what is in the mammoth haul of documents—not the NSA, not the custodians, not even Snowden himself. He would not say exactly how he gathered them, but others in the intelligence community have speculated that he simply used a web crawler, a program that can search for and copy all documents containing particular keywords or combinations of keywords. This could account for many of the documents that simply list highly technical and nearly unintelligible signal parameters and other statistics.

And there’s another prospect that further complicates matters: Some of the revelations attributed to Snowden may not in fact have come from him but from another leaker spilling secrets under Snowden’s name. Snowden himself adamantly refuses to address this possibility on the record. But independent of my visit to Snowden, I was given unrestricted access to his cache of documents in various locations. And going through this archive using a sophisticated digital search tool, I could not find some of the documents that have made their way into public view, leading me to conclude that there must be a second leaker somewhere. I’m not alone in reaching that conclusion. Both Greenwald and security expert Bruce Schneier—who have had extensive access to the cache—have publicly stated that they believe another whistle-blower is releasing secret documents to the media.

In fact, on the first day of my Moscow interview with Snowden, the German newsmagazine Der Spiegel comes out with a long story about the NSA’s operations in Germany and its cooperation with the German intelligence agency, BND. Among the documents the magazine releases is a top-secret “Memorandum of Agreement” between the NSA and the BND from 2002. “It is not from Snowden’s material,” the magazine notes.

Some have even raised doubts about whether the infamous revelation that the NSA was tapping German chancellor Angela Merkel’s cell phone, long attributed to Snowden, came from his trough. At the time of that revelation, Der Spiegel simply attributed the information to Snowden and other unnamed sources. If other leakers exist within the NSA, it would be more than another nightmare for the agency—it would underscore its inability to control its own information and might indicate that Snowden’s rogue protest of government overreach has inspired others within the intelligence community. “They still haven’t fixed their problems,” Snowden says. “They still have negligent auditing, they still have things going for a walk, and they have no idea where they’re coming from and they have no idea where they’re going. And if that’s the case, how can we as the public trust the NSA with all of our information, with all of our private records, the permanent record of our lives?”

The Der Spiegel articles were written by, among others, Poitras, the filmmaker who was one of the first journalists Snowden contacted. Her high visibility and expertise in encryption may have attracted other NSA whistle-blowers, and Snowden’s cache of documents could have provided the ideal cover. Following my meetings with Snowden, I email Poitras and ask her point-blank whether there are other NSA sources out there. She answers through her attorney: “We are sorry but Laura is not going to answer your question.”

The same day I share pizza with Snowden in a Moscow hotel room, the US House of Representatives moves to put the brakes on the NSA. By a lopsided 293-to-123 tally, members vote to halt the agency’s practice of conducting warrantless searches of a vast database that contains millions of Americans’ emails and phone calls. “There’s no question Americans have become increasingly alarmed with the breadth of unwarranted government surveillance programs used to store and search their private data,” the Democratic and Republican sponsors announce in a joint statement. “By adopting this amendment, Congress can take a sure step toward shutting the back door on mass surveillance.”

It’s one of many proposed reforms that never would have happened had it not been for Snowden. Back in Moscow, Snowden recalls boarding a plane for Hong Kong, on his way to reveal himself as the leaker of a spectacular cache of secrets and wondering whether his risk would be worth it. “I thought it was likely that society collectively would just shrug and move on,” he says. Instead, the NSA’s surveillance has become one of the most pressing issues in the national conversation. President Obama has personally addressed the issue, Congress has taken up the issue, and the Supreme Court has hinted that it may take up the issue of warrantless wiretapping. Public opinion has also shifted in favor of curtailing mass surveillance. “It depends a lot on the polling question,” he says, “but if you ask simply about things like my decision to reveal Prism”—the program that allows government agencies to extract user data from companies like Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo—“55 percent of Americans agree. Which is extraordinary given the fact that for a year the government has been saying I’m some kind of supervillain.”

That may be an overstatement, but not by much. Nearly a year after Snowden’s first leaks broke, NSA director Keith Alexander claimed that Snowden was “now being manipulated by Russian intelligence” and accused him of causing “irreversible and significant damage.” More recently, Secretary of State John Kerry said that “Edward Snowden is a coward, he is a traitor, and he has betrayed his country.” But in June, the government seemed to be backing away from its most apocalyptic rhetoric. In an interview with The New York Times, the new head of the NSA, Michael Rogers, said he was “trying to be very specific and very measured in my characterizations”: “You have not heard me as the director say, ‘Oh my God, the sky is falling.’”

Snowden keeps close tabs on his evolving public profile, but he has been resistant to talking about himself. In part, this is because of his natural shyness and his reluctance about “dragging family into it and getting a biography.” He says he worries that sharing personal details will make him look narcissistic and arrogant. But mostly he’s concerned that he may inadvertently detract from the cause he has risked his life to promote. “I’m an engineer, not a politician,” he says. “I don’t want the stage. I’m terrified of giving these talking heads some distraction, some excuse to jeopardize, smear, and delegitimize a very important movement.”

But when Snowden finally agrees to discuss his personal life, the portrait that emerges is not one of a wild-eyed firebrand but of a solemn, sincere idealist who—step by step over a period of years—grew disillusioned with his country and government.

But when Snowden finally agrees to discuss his personal life, the portrait that emerges is not one of a wild-eyed firebrand but of a solemn, sincere idealist who—step by step over a period of years—grew disillusioned with his country and government.

Born on June 21, 1983, Snowden grew up in the Maryland suburbs, not far from the NSA’s headquarters. His father, Lon, rose through the enlisted ranks of the Coast Guard to warrant officer, a difficult path. His mother, Wendy, worked for the US District Court in Baltimore, while his older sister, Jessica, became a lawyer at the Federal Judicial Center in Washington. “Everybody in my family has worked for the federal government in one way or another,” Snowden says. “I expected to pursue the same path.” His father told me, “We always considered Ed the smartest one in the family.” It didn’t surprise him when his son scored above 145 on two separate IQ tests.

Rather than spending hours watching television or playing sports as a kid, Snowden fell in love with books, especially Greek mythology. “I remember just going into those books, and I would disappear with them for hours,” he says. Snowden says reading about myths played an important role growing up, providing him with a framework for confronting challenges, including moral dilemmas. “I think that’s when I started thinking about how we identify problems, and that the measure of an individual is how they address and confront those problems,” he says.

Soon after Snowden revealed himself as a leaker, there was enormous media focus on the fact that he quit school after the 10th grade, with the implication that he was simply an uneducated slacker. But rather than delinquency, it was a bout of mononucleosis that caused him to miss school for almost nine months. Instead of falling back a grade, Snowden enrolled in community college. He’d loved computers since he was a child, but now that passion deepened. He started working for a classmate who ran his own tech business. Coincidentally, the company was run from a house at Fort Meade, where the NSA’s headquarters are located.

Snowden was on his way to the office when the 9/11 attacks took place. “I was driving in to work and I heard the first plane hit on the radio,” he says. Like a lot of civic-minded Americans, Snowden was profoundly affected by the attacks. In the spring of 2004, as the ground war in Iraq was heating up with the first battle of Fallujah, he volunteered for the Army special forces. “I was very open to the government’s explanation—almost propaganda—when it came to things like Iraq, aluminum tubes, and vials of anthrax,” he says. “I still very strongly believed that the government wouldn’t lie to us, that our government had noble intent, and that the war in Iraq was going to be what they said it was, which was a limited, targeted effort to free the oppressed. I wanted to do my part.”

Snowden says that he was particularly attracted to the special forces because it offered the chance to learn languages. After performing well on an aptitude test, he was admitted. But the physical requirements were more challenging. He broke both of his legs in a training accident. A few months later he was discharged.

Out of the Army, Snowden landed a job as a security guard at a top-secret facility that required him to get a high-level security clearance. He passed a polygraph exam and the stringent background check and, almost without realizing it, he found himself on his way to a career in the clandestine world of intelligence. After attending a job fair focused on intelligence agencies, he was offered a position at the CIA, where he was assigned to the global communications division, the organization that deals with computer issues, at the agency’s headquarters in Langley, Virginia. It was an extension of the network and engineering work he’d been doing since he was 16. “All of the covert sites—cover sites and so forth—they all network into the CIA headquarters,” he says. “It was me and one other guy who worked the late shifts.” But Snowden quickly discovered one of the CIA’s biggest secrets: Despite its image as a bleeding-edge organization, its technology was woefully out-of-date. The agency was not at all what it appeared to be from the outside.

As the junior man on the top computer team, Snowden distinguished himself enough to be sent to the CIA’s secret school for technology specialists. He lived there, in a hotel, for some six months, studying and training full-time. After the training was complete, in March 2007, Snowden headed for Geneva, Switzerland, where the CIA was seeking information about the banking industry. He was assigned to the US Mission to the United Nations. He was given a diplomatic passport, a four-bedroom apartment near the lake, and a nice cover assignment.

It was in Geneva that Snowden would see firsthand some of the moral compromises CIA agents made in the field. Because spies were promoted based on the number of human sources they recruited, they tripped over each other trying to sign up anyone they could, regardless of their value. Operatives would get targets drunk enough to land in jail and then bail them out—putting the target in their debt. “They do really risky things to recruit them that have really negative, profound impacts on the person and would have profound impacts on our national reputation if we got caught,” he says. “But we do it simply because we can.”

While in Geneva, Snowden says, he met many spies who were deeply opposed to the war in Iraq and US policies in the Middle East. “The CIA case officers were all going, what the hell are we doing?” Because of his job maintaining computer systems and network operations, he had more access than ever to information about the conduct of the war. What he learned troubled him deeply. “This was the Bush period, when the war on terror had gotten really dark,” he says. “We were torturing people; we had warrantless wiretapping.”

He began to consider becoming a whistle-blower, but with Obama about to be elected, he held off. “I think even Obama’s critics were impressed and optimistic about the values that he represented,” he says. “He said that we’re not going to sacrifice our rights. We’re not going to change who we are just to catch some small percentage more terrorists.” But Snowden grew disappointed as, in his view, Obama didn’t follow through on his lofty rhetoric. “Not only did they not fulfill those promises, but they entirely repudiated them,” he says. “They went in the other direction. What does that mean for a society, for a democracy, when the people that you elect on the basis of promises can basically suborn the will of the electorate?”

It took a couple of years for this new level of disillusionment to set in. By that time—2010—Snowden had shifted from the CIA to the NSA, accepting a job as a technical expert in Japan with Dell, a major contractor for the agency. Since 9/11 and the enormous influx of intelligence money, much of the NSA’s work had been outsourced to defense contractors, including Dell and Booz Allen Hamilton. For Snowden, the Japan posting was especially attractive: He had wanted to visit the country since he was a teen. Snowden worked at the NSA offices at Yokota Air Base, outside Tokyo, where he instructed top officials and military officers on how to defend their networks from Chinese hackers.

But Snowden’s disenchantment would only grow. It was bad enough when spies were getting bankers drunk to recruit them; now he was learning about targeted killings and mass surveillance, all piped into monitors at the NSA facilities around the world. Snowden would watch as military and CIA drones silently turned people into body parts. And he would also begin to appreciate the enormous scope of the NSA’s surveillance capabilities, an ability to map the movement of everyone in a city by monitoring their MAC address, a unique identifier emitted by every cell phone, computer, and other electronic device.

Even as his faith in the mission of US intelligence services continued to crumble, his upward climb as a trusted technical expert proceeded. In 2011 he returned to Maryland, where he spent about a year as Dell’s lead technologist working with the CIA’s account. “I would sit down with the CIO of the CIA, the CTO of the CIA, the chiefs of all the technical branches,” he says. “They would tell me their hardest technology problems, and it was my job to come up with a way to fix them.”

But in March 2012, Snowden moved again for Dell, this time to a massive bunker in Hawaii where he became the lead technologist for the information-sharing office, focusing on technical issues. Inside the “tunnel,” a dank, chilly, 250,000-square-foot pit that was once a torpedo storage facility, Snowden’s concerns over the NSA’s capabilities and lack of oversight grew with each passing day. Among the discoveries that most shocked him was learning that the agency was regularly passing raw private communications—content as well as metadata—to Israeli intelligence. Usually information like this would be “minimized,” a process where names and personally identifiable data are removed. But in this case, the NSA did virtually nothing to protect even the communications of people in the US. This included the emails and phone calls of millions of Arab and Palestinian Americans whose relatives in Israel-occupied Palestine could become targets based on the communications. “I think that’s amazing,” Snowden says. “It’s one of the biggest abuses we’ve seen.” (The operation was reported last year by The Guardian, which cited the Snowden documents as its source.)

Another troubling discovery was a document from NSA director Keith Alexander that showed the NSA was spying on the pornography-viewing habits of political radicals. The memo suggested that the agency could use these “personal vulnerabilities” to destroy the reputations of government critics who were not in fact accused of plotting terrorism. The document then went on to list six people as future potential targets. (Greenwald published a redacted version of the document last year on the Huffington Post.)

Snowden was astonished by the memo. “It’s much like how the FBI tried to use Martin Luther King’s infidelity to talk him into killing himself,” he says. “We said those kinds of things were inappropriate back in the ’60s. Why are we doing that now? Why are we getting involved in this again?”

In the mid-1970s, Senator Frank Church, similarly shocked by decades of illegal spying by the US intelligence services, first exposed the agencies’ operations to the public. That opened the door to long-overdue reforms, such as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act. Snowden sees parallels between then and now. “Frank Church analogized it as being on the brink of the abyss,” he says. “He was concerned that once we went in we would never come out. And the concern we have today is that we’re on the brink of that abyss again.” He realized, just like Church had before him, that the only way to cure the abuses of the government was to expose them. But Snowden didn’t have a Senate committee at his disposal or the power of congressional subpoena. He’d have to carry out his mission covertly, just as he’d been trained.

The sun sets late here in June, and outside the hotel window long shadows are beginning to envelop the city. But Snowden doesn’t seem to mind that the interview is stretching into the evening hours. He is living on New York time, the better to communicate with his stateside supporters and stay on top of the American news cycle. Often, that means hearing in almost real time the harsh assessments of his critics. Indeed, it’s not only government apparatchiks that take issue with what Snowden did next—moving from disaffected operative to whistle-blowing dissident. Even in the technology industry, where he has many supporters, some accuse him of playing too fast and loose with dangerous information. Netscape founder and prominent venture capitalist Marc Andreessen has told CNBC, “If you looked up in the encyclopedia ‘traitor,’ there’s a picture of Edward Snowden.” Bill Gates delivered a similarly cutting assessment in a Rolling Stone interview. “I think he broke the law, so I certainly wouldn’t characterize him as a hero,” he said. “You won’t find much admiration from me.”

Snowden adjusts his glasses; one of the nose pads is missing, making them slip occasionally. He seems lost in thought, looking back to the moment of decision, the point of no return. The time when, thumb drive in hand, aware of the enormous potential consequences, he secretly went to work. “If the government will not represent our interests,” he says, his face serious, his words slow, “then the public will champion its own interests. And whistle-blowing provides a traditional means to do so.”

Snowden adjusts his glasses; one of the nose pads is missing, making them slip occasionally. He seems lost in thought, looking back to the moment of decision, the point of no return. The time when, thumb drive in hand, aware of the enormous potential consequences, he secretly went to work. “If the government will not represent our interests,” he says, his face serious, his words slow, “then the public will champion its own interests. And whistle-blowing provides a traditional means to do so.”

The NSA had apparently never predicted that someone like Snowden might go rogue. In any case, Snowden says he had no problem accessing, downloading, and extracting all the confidential information he liked. Except for the very highest level of classified documents, details about virtually all of the NSA’s surveillance programs were accessible to anyone, employee or contractor, private or general, who had top-secret NSA clearance and access to an NSA computer.

But Snowden’s access while in Hawaii went well beyond even this. “I was the top technologist for the information-sharing office in Hawaii,” he says. “I had access to everything.”

Well, almost everything. There was one key area that remained out of his reach: the NSA’s aggressive cyberwarfare activity around the world. To get access to that last cache of secrets, Snowden landed a job as an infrastructure analyst with another giant NSA contractor, Booz Allen. The role gave him rare dual-hat authority covering both domestic and foreign intercept capabilities—allowing him to trace domestic cyberattacks back to their country of origin. In his new job, Snowden became immersed in the highly secret world of planting malware into systems around the world and stealing gigabytes of foreign secrets. At the same time, he was also able to confirm, he says, that vast amounts of US communications “were being intercepted and stored without a warrant, without any requirement for criminal suspicion, probable cause, or individual designation.” He gathered that evidence and secreted it safely away.

By the time he went to work for Booz Allen in the spring of 2013, Snowden was thoroughly disillusioned, yet he had not lost his capacity for shock. One day an intelligence officer told him that TAO—a division of NSA hackers—had attempted in 2012 to remotely install an exploit in one of the core routers at a major Internet service provider in Syria, which was in the midst of a prolonged civil war. This would have given the NSA access to email and other Internet traffic from much of the country. But something went wrong, and the router was bricked instead—rendered totally inoperable. The failure of this router caused Syria to suddenly lose all connection to the Internet—although the public didn’t know that the US government was responsible. (This is the first time the claim has been revealed.)

Inside the TAO operations center, the panicked government hackers had what Snowden calls an “oh shit” moment. They raced to remotely repair the router, desperate to cover their tracks and prevent the Syrians from discovering the sophisticated infiltration software used to access the network. But because the router was bricked, they were powerless to fix the problem.

Fortunately for the NSA, the Syrians were apparently more focused on restoring the nation’s Internet than on tracking down the cause of the outage. Back at TAO’s operations center, the tension was broken with a joke that contained more than a little truth: “If we get caught, we can always point the finger at Israel.”

Much of Snowden’s focus while working for Booz Allen was analyzing potential cyberattacks from China. His targets included institutions normally considered outside the military’s purview. He thought the work was overstepping the intelligence agency’s mandate. “It’s no secret that we hack China very aggressively,” he says. “But we’ve crossed lines. We’re hacking universities and hospitals and wholly civilian infrastructure rather than actual government targets and military targets. And that’s a real concern.”

The last straw for Snowden was a secret program he discovered while getting up to speed on the capabilities of the NSA’s enormous and highly secret data storage facility in Bluffdale, Utah. Potentially capable of holding upwards of a yottabyte of data, some 500 quintillion pages of text, the 1 million-square-foot building is known within the NSA as the Mission Data Repository. (According to Snowden, the original name was Massive Data Repository, but it was changed after some staffers thought it sounded too creepy—and accurate.) Billions of phone calls, faxes, emails, computer-to-computer data transfers, and text messages from around the world flow through the MDR every hour. Some flow right through, some are kept briefly, and some are held forever.

The massive surveillance effort was bad enough, but Snowden was even more disturbed to discover a new, Strangelovian cyberwarfare program in the works, codenamed MonsterMind. The program, disclosed here for the first time, would automate the process of hunting for the beginnings of a foreign cyberattack. Software would constantly be on the lookout for traffic patterns indicating known or suspected attacks. When it detected an attack, MonsterMind would automatically block it from entering the country—a “kill” in cyber terminology.

Programs like this had existed for decades, but MonsterMind software would add a unique new capability: Instead of simply detecting and killing the malware at the point of entry, MonsterMind would automatically fire back, with no human involvement. That’s a problem, Snowden says, because the initial attacks are often routed through computers in innocent third countries. “These attacks can be spoofed,” he says. “You could have someone sitting in China, for example, making it appear that one of these attacks is originating in Russia. And then we end up shooting back at a Russian hospital. What happens next?”

In addition to the possibility of accidentally starting a war, Snowden views MonsterMind as the ultimate threat to privacy because, in order for the system to work, the NSA first would have to secretly get access to virtually all private communications coming in from overseas to people in the US. “The argument is that the only way we can identify these malicious traffic flows and respond to them is if we’re analyzing all traffic flows,” he says. “And if we’re analyzing all traffic flows, that means we have to be intercepting all traffic flows. That means violating the Fourth Amendment, seizing private communications without a warrant, without probable cause or even a suspicion of wrongdoing. For everyone, all the time.” (A spokesperson for the NSA declined to comment on MonsterMind, the malware in Syria, or on the specifics of other aspects of this article.)

Given the NSA’s new data storage mausoleum in Bluffdale, its potential to start an accidental war, and the charge to conduct surveillance on all incoming communications, Snowden believed he had no choice but to take his thumb drives and tell the world what he knew. The only question was when.

On March 13, 2013, sitting at his desk in the “tunnel” surrounded by computer screens, Snowden read a news story that convinced him that the time had come to act. It was an account of director of national intelligence James Clapper telling a Senate committee that the NSA does “not wittingly” collect information on millions of Americans. “I think I was reading it in the paper the next day, talking to coworkers, saying, can you believe this shit?”

Snowden and his colleagues had discussed the routine deception around the breadth of the NSA’s spying many times, so it wasn’t surprising to him when they had little reaction to Clapper’s testimony. “It was more of just acceptance,” he says, calling it “the banality of evil”—a reference to Hannah Arendt’s study of bureaucrats in Nazi Germany.

“It’s like the boiling frog,” Snowden tells me. “You get exposed to a little bit of evil, a little bit of rule-breaking, a little bit of dishonesty, a little bit of deceptiveness, a little bit of disservice to the public interest, and you can brush it off, you can come to justify it. But if you do that, it creates a slippery slope that just increases over time, and by the time you’ve been in 15 years, 20 years, 25 years, you’ve seen it all and it doesn’t shock you. And so you see it as normal. And that’s the problem, that’s what the Clapper event was all about. He saw deceiving the American people as what he does, as his job, as something completely ordinary. And he was right that he wouldn’t be punished for it, because he was revealed as having lied under oath and he didn’t even get a slap on the wrist for it. It says a lot about the system and a lot about our leaders.” Snowden decided it was time to hop out of the water before he too was boiled alive.

At the same time, he knew there would be dire consequences. “It’s really hard to take that step—not only do I believe in something, I believe in it enough that I’m willing to set my own life on fire and burn it to the ground.”

But he felt that he had no choice. Two months later he boarded a flight to Hong Kong with a pocket full of thumb drives.

The afternoon of our third meeting, about two weeks after our first, Snowden comes to my hotel room. I have changed locations and am now staying at the Hotel National, across the street from the Kremlin and Red Square. An icon like the Metropol, much of Russia’s history passed through its front doors at one time or another. Lenin once lived in Room 107, and the ghost of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the feared chief of the old Soviet secret police who also lived here, still haunts the hallways.

But rather than the Russian secret police, it’s his old employers, the CIA and the NSA, that Snowden most fears. “If somebody’s really watching me, they’ve got a team of guys whose job is just to hack me,” he says. “I don’t think they’ve geolocated me, but they almost certainly monitor who I’m talking to online. Even if they don’t know what you’re saying, because it’s encrypted, they can still get a lot from who you’re talking to and when you’re talking to them.”

More than anything, Snowden fears a blunder that will destroy all the progress toward reforms for which he has sacrificed so much. “I’m not self-destructive. I don’t want to self-immolate and erase myself from the pages of history. But if we don’t take chances, we can’t win,” he says. And so he takes great pains to stay one step ahead of his presumed pursuers—he switches computers and email accounts constantly. Nevertheless, he knows he’s liable to be compromised eventually: “I’m going to slip up and they’re going to hack me. It’s going to happen.”

Indeed, some of his fellow travelers have already committed some egregious mistakes. Last year, Greenwald found himself unable to open a large trove of NSA secrets that Snowden had passed to him. So he sent his longtime partner, David Miranda, from their home in Rio to Berlin to get another set from Poitras, who fixed the archive. But in making the arrangements, The Guardian booked a transfer through London. Tipped off, probably as a result of surveillance by GCHQ, the British counterpart of the NSA, British authorities detained Miranda as soon as he arrived and questioned him for nine hours. In addition, an external hard drive containing 60 gigabits of data—about 58,000 pages of documents—was seized. Although the documents had been encrypted using a sophisticated program known as True Crypt, the British authorities discovered a paper of Miranda’s with the password for one of the files, and they were able to decrypt about 75 pages, according to British court documents. *

Another concern for Snowden is what he calls NSA fatigue—the public becoming numb to disclosures of mass surveillance, just as it becomes inured to news of battle deaths during a war. “One death is a tragedy, and a million is a statistic,” he says, mordantly quoting Stalin. “Just as the violation of Angela Merkel’s rights is a massive scandal and the violation of 80 million Germans is a nonstory.”

Nor is he optimistic that the next election will bring any meaningful reform. In the end, Snowden thinks we should put our faith in technology—not politicians. “We have the means and we have the technology to end mass surveillance without any legislative action at all, without any policy changes.” The answer, he says, is robust encryption. “By basically adopting changes like making encryption a universal standard—where all communications are encrypted by default—we can end mass surveillance not just in the United States but around the world.”

Until then, Snowden says, the revelations will keep coming. “We haven’t seen the end,” he says. Indeed, a couple of weeks after our meeting, The Washington Post reported that the NSA’s surveillance program had captured much more data on innocent Americans than on its intended foreign targets. There are still hundreds of thousands of pages of secret documents out there—to say nothing of the other whistle-blowers he may have already inspired. But Snowden says that information contained in any future leaks is almost beside the point. “The question for us is not what new story will come out next. The question is, what are we going to do about it?”

*Correction appended [10:55am/August, 22 2014]: An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported that Miranda retrieved GCHQ documents from Poitras; it also incorrectly stated that Greenwald has not gained access to the complete GCHQ documents.

(wired.com)