Tomás Milián in Cuba, closing circles

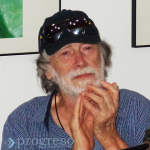

HAVANA.- Tomás Milián is back in Havana. After 60 years without visiting the city where he was born on March 5, 1933, he has come to receive an homage prepared by the Cuban Cinematheque that includes a retrospective of the films he has played in, throughout his long career.

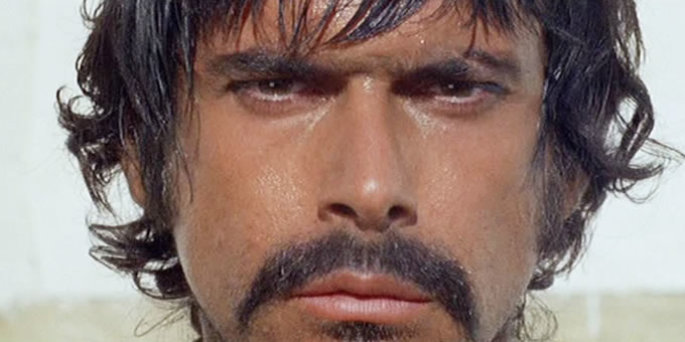

Tomás Quintín Rodríguez Milián left Cuba at the age of 21 with the firm intention of becoming an actor. The first thing he did after arriving in New York City was show up at the Actors Studio, where he was told he should improve his English.

After a short stint in the U.S. Navy, where he improved his English, he returned to the Actors Studio, did two auditions and was selected out of 3,000 candidates. He joined the Studio on Dec. 18, 1957. Until today, he is the only Cuban to be accepted by the Studio. That day, he received the first applause of his life.

His later history is succulent: Italy, France, Mauro Bolognini, Luchino Visconti, Michelangelo Antonioni; Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci; Hollywood, Sidney Pollack, Oliver Stone, Steven Spielberg, Steven Soderbergh.

At 81, Tomás Milián is full of life. He displays a perennial sense of humor, an indisputable mark of his Cubanness, adorned by the frequent “ecco” and “anyway” that are imprinted in his speech. He said he was very happy to be back in Havana, which he found almost the same as when he left it.

SM: At the meeting you held with the press, producers and specialists, you said that, as a youth, you were a “retama de guayacol” (an unlovable guy). How can a man who left his homeland 60 years ago and didn’t return until today use such a Cuban expression in such an organic and natural manner?

TM: I didn’t use it since I left Cuba, but being back here is taking me back to the Cuban wiseguy I once was.

SM: Did you say that you found Havana almost the way you left it?

TM: Yes, because I found everything that I looked for, everything that meant something to me. The houses are there; damaged and mouldy with the passing of time, but they’re there.

SM: Despite the limited exchange you’ve had with your compatriots so far, how do you feel?

TM: I’ve been talking with Cubans like myself and it gives me pleasure. I notice a bit of curiosity but also a bit of tenderness in the people — and in you.

SM: You inspire it.

TM: Thank you, thank you. I am happy, I am content. This seems like a dream. It seems that I’ll wake up tomorrow and none of this will be true. I love this reception you’ve given me, I love to see my photographs on the wall at the exhibition. It’s the first time this happens to me and it’s all new to me.

SM: How did you come to the Indian culture?

TM: I arrived in India on a journey of desperation, at a time when I was leading a very irregular life. I felt that if I remained on that path I wouldn’t end up well. I read in an Italian magazine about a guru and said to my wife, “You know, Rita? I’m going to India to find this guru who allegedly performs miracles, because only a miracle can change me.”

I went to find the guru so he could help me, because the Catholic religion couldn’t. But I have this religious feeling that helps me to live, thinking that there is something that I can earn with patience, pain, or whatever.

Something happens to the human being in moments of desperation when you think that you can’t go on and are not mad enough to kill yourself — like my father did — and you think that this guru will cure you. But it’s not the man, it’s the trip you make, so far, so difficult, so painful, that when you kneel at his feet, that gesture of humility, of desperation, those tears that come when he stops walking and touches your head, I mean, he noticed you, that and the fresh tears of joy and commotion… that cures you, but it’s nothing more than faith, because he’s a man just like you, who has let his hair grow and wears a saffron robe and walks so slowly that he seems to be walking on clouds, and you feel as if you were in the sky with him and he cures you. But it is you who cures yourself with faith and love.

SM: Are these photos an expression of that cure?

TM: Ecco, exactly. One day in India, I was holding a camera and I saw a stain on the wall and photographed it, and I so enjoyed the sensation of painting with my eyes something that was there by chance that I began to look for walls that had stains, so I could paint without paint, I mean, paint the stains of time with my eyes. I also looked for them in Rome, Venice, New York and Miami.

Those are my photos, displayed at the exhibition “Walls” at the ICAIC’s Center for Cinematographic Promotion.

When I started, I fell in love with walls. My acting shifted to the background. It was as if I had found a new way to express myself. Not really, though. It was a moment in which I felt the need to make those pictures, a passing moment. Since then, I’ve taken no more pictures. Photography no longer interests me.

SM: Of the many cinema directors with whom you worked in your long career, from whom did you learn the most?

TM: Learn? I am an actor and I learned nothing, not even in the Actors Studio. I am an actor and I’ve been one since birth. I think that when I left my mother’s uterus I was already acting. A cry of pain that marked my entire life.

SM: ‘Lost City,’ directed in 2006 by Cuban-American actor Andy García, suffers from many historical inaccuracies but manages to recreate a Cuban environment, especially in terms of family life, much enhanced by your performance as Don Federico Fellove. How did you build this character? Did you pattern him after someone in your family?

TM: Yes, my grandfather was like that. He was a patriarch. He sat at the head of the table, with his family all around. Yes, Fellove came out of my memories, out of the place where I grew up. It was a very emotional thing.

It was so emotional that, in the scene where we’re all at the table waiting for Andy and he arrives, I remind him what time it is, and he kisses me on the head, I couldn’t control myself and burst into tears, because Andy is a very tender person, very loving. He’s not false, he’s authentic. Also, because everything was so authentic on the set — the furniture, things, the family, me myself — I was very much moved.

SM: The scene where Fellove bids farewell to his son who’s leaving for the United States is also very authentic, yet you didn’t live the farewells of the Cuban families who left for the U.S.

TM: I did live that moment in the film, because — feeling like my grandfather — I wasn’t inventing feelings. Although I didn’t leave Cuba, didn’t emigrate as they did then, I did emigrate in that film, and everything you saw I felt in my own skin. That’s why I burst into tears, because the situation was so real that I couldn’t contain… Besides, the farewell, the hugs, the wife crying, and you’re trying not to cry and your departing son cries… no, no.

SM: What was it like to work under the direction of your compatriot Andy García?

TM: With Andy, everything had to be very real. Even the Guerlain cologne on the bedside table, in the scene where I’m in bed talking with him, I took it to the set from home. But it was a small bottle. I should have taken the big bottle, the pretty one. You don’t see it in the finished film, but it was there and I knew it was. That was enough.

Andy is very pure, very kind; he’s a “cubano rellollo” (native Cuban) like those Cubans from Pinar del Río. I don’t know why that region produces so many good people.

Here’s a detail from Andy’s direction. In one scene, a character at a bar asks for a cup of coffee and drinks it from the saucer. My God, I said, what is this?

SM: So you got along well, Cuban to Cuban?

TM: Yes, of course. But anyway, who doesn’t get along with Andy? We are friends. There’s no need to see each other or phone each other. That’s a relationship for life. It’s part of my memories, of me, of my family.

I asked Andy for a song that moves me a lot, because it reminds me of my grandparents. It’s “Veinte años” by María Teresa Vera. And he included it in the movie just to please me.

I felt very good doing this movie. It was like closing a circle in my life; not the last one, because there’s more circles to close.

SM: Will this visit to Cuba be another circle that closes in your life?

TM: Sure, this is another important circle that closes.