Cuba’s economy: Revisiting what should have already been started

HAVANA – Alejandro Gil, Cuba’s Minister of Economy, last week presented a summary of the country’s critical economic situation to the Cuban Parliament. It is a state of affairs well-known among most on the streets, but a detailed inventory of the specific problems, along with possible solutions and long-term plans, puts them at the forefront. From there, the next steps proposed by the Minister can almost be called soft, alleviating hands to lessen the pressure applied by the rope around our necks.

The economy, like any system, can not be analyzed in plots, as if each element is not intrinsically related to the others and influences, directly or not, numbers that are not painted red. They also reach levels of a national security that includes everyone.

Cuba’s Minister of the Economy describes the economic crisis

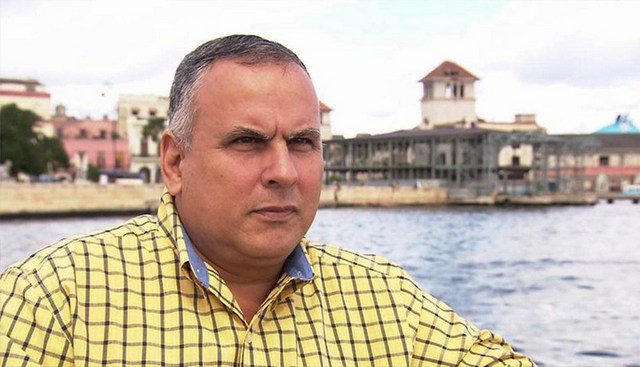

“Sectors that have been discussed for years are really where Cuba should focus, areas that can generate sustained growth quickly,” explained Cuban economist Omar Everleny. It is how he explains the six economic activities proposed as priorities over the next three years, which correspond to the first stage of the National Plan for Economic and Social Development (PNDES) for 2030. A plan that has three stages, six sectors, a sovereign nation and its millions of daughters and sons.

Professor Everleny says there are internal problems related, among other factors, to centralized planning, so the state of affairs also merits an analysis of these fundamental obstacles that have been holding back the efficiency of economic dynamics for years. “This is not the first time that ideas and long-term projects have been raised,” he says, adding, “but there are macroeconomic problems, deformations of the domestic economy that are not resolved by giving priority to certain sectors.”

The chosen sectors

One of the main problems presented by tourism has to do with investments beyond the hotels, a point that has not gone unnoticed by the authorities, and in which Everleny agrees.

“The issue is efficiency. The quality of what a tourist who comes to Cuba receives is far below what the same tourist obtains in the region, as for example in Punta Cana. Hotel capacity would be needed, but at this moment we still have a level of occupation quite low compared to the area –38.5 percent in 2018, according to figures from the National Bureau of Statistics and Information, so we should also think about the activities that support tourism and produce more revenue to the country.”

He estimates that the issue of road infrastructure, food production and the water supply in some areas of the Central Havana and Old Havana is also vital for the growth of this activity. “It would be necessary to allocate more resources to the physical infrastructure. That was done whey they invested in Varadero. Many of those investments that were made in Matanzas and on the road that linked the province with the peninsula came from tourism funds,” Everleny explains.

Tourism Development Director Daniel Alonso reported in March that in 2019 they had planned for the construction of 3,805 new hotel rooms on the Island. A figure that does not approximate the 5,000 proposed last November by Tourism Minister Manuel Marrero.

“It would be feasible for the country to think about dedicating part of the investment planned for the construction of this large number of rooms to improving the infrastructure we are talking about,” said Everleny.

Regarding the biotechnological and pharmaceutical industry, the economics professor agrees with the excellent results achieved over the years, especially because of the quality of its products. However, “it was thought that with the Obama rapprochement there could be a greater exchange with the United States in that regard. Unfortunately most of the companies in the world of biotechnology are transnational, and many of them are from the U.S. A favorable deal was reached when it was decided to work on the vaccine against lung cancer with an institute from that country, but the recent Trump administration measures do not favor this type of agreement.” He feels this would be the main obstacle to this chosen sector under current circumstances. “It is also not easy,” he adds, “to approve a Cuban product for marketing, even when it is of the highest quality, because we are talking about a very expensive industry.”

Food production is another case in point, although the renewed tightening of the U.S. blockade against Cuba affects the entire Cuban economy. “If there’s an area where major economic reforms have taken place in the past few years, it is precisely in agriculture. But there are many things still happening. Firstly, Acopio [the country’s entity that acquires and distributes products] sets prices, and nowhere in the world does the buyer set the price. During the revolutionary stage this entity had its moments of boom and decline, but above all, the latter. And yet, we keep betting on this centralized model,” said Everleny.

This inefficiency persists today as shown by the failure of the plan when Minister Gustavo Rodríguez Rollero explained it last March in Parliament. More specifically, 12,000 tons of root vegetables, vegetables, grains and fruits that were not be collected and therefore lost [by Acopio]. And yet, instead of reducing bureaucracy and centralization of this and other institutions, one of the measures announced by Rollero was that Acopio should “soon become a Superior Organization of Business Management, with entities in each province and a new one in Havana.” All the while, in Cuba this year, “more than five billion dollars in food and fuel” are being imported, according to Minister Alejandro Gil.

Another possibility that Everleny espouses is that producers directly access the international trade market to find supplies and technologies with their own resources, something that the state has not been able to guarantee in a stable and sustainable way for many years. “Most of the country’s agricultural production, except for sugarcane, is in the hands of private producers,” he says.

“I think that rather than identifying sectors (and I am not saying not to do it; I think it is also valid), we should think of a greater internal freedom [to get things done],” adds the economist. “The external factors for the country are complex, but Cuba does not have the strength to influence these issues much. What is available to the government is to put into effect what has already been discussed and approved, which is nothing new.”

The professor is referring to documents such as the proposed Guidelines, where few have been implemented since they were introduced in 2013; the Conceptualization of the Economic Model, which required more than five years of discussions to achieve a final version; and the new Cuban Constitution, where an assortment of different properties are recognized, for example.

“Why not approve small- and medium-sized companies if you would not be violating any law? Why not allow that non-state sector to import?” he asks.

“The decision-making process has a different timeline than that of ordinary Cubans,” says Everleny, and concludes, “I think it’s time to synchronize our clocks, because the Cuban people did not exit the first special period. Not everyone was able to recover what they lost.”