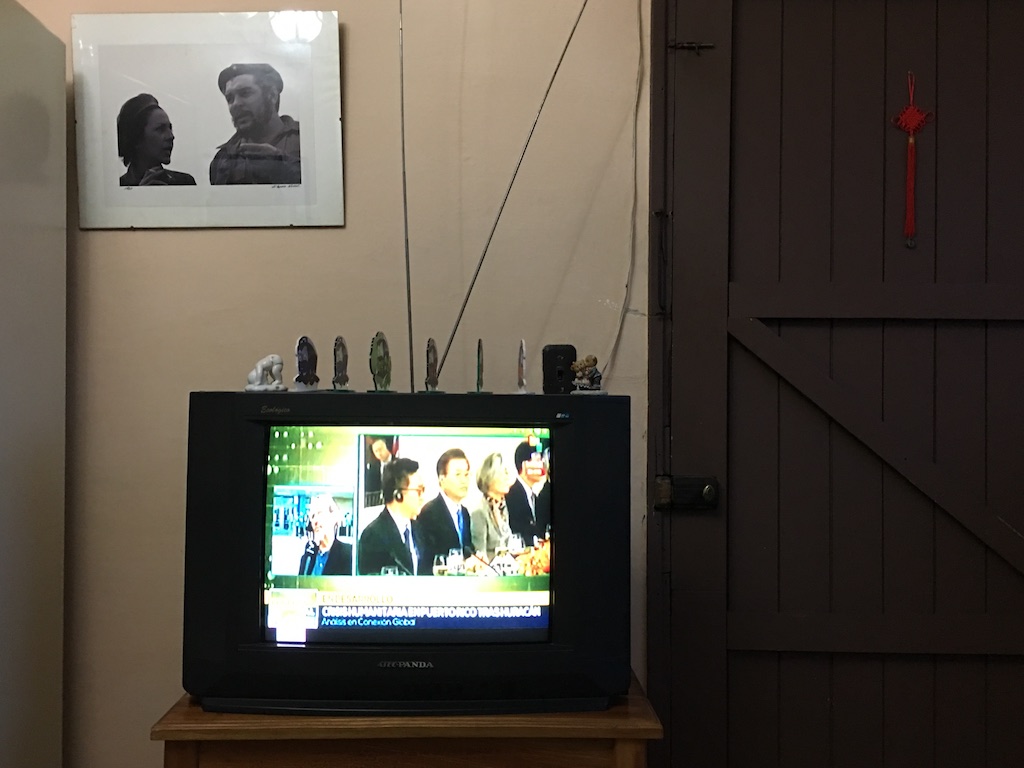

The idiot box

It must be awfully difficult for U.S. editors to fact check stories they receive about Cuba, given that their own knowledge of the country is so slim. It might also be too much bother to find, or pay, a Cuban in Cuba to do it, although there are plenty of Cubans who could.

My 11 year old son, for example, who as I read an article published by Harper’s this summer about Cuban television, was reading over my shoulder and chuckled at the claim that iPhones are illegal here. “That’s not true,” he smirked.

The article‘s focus was El Paquete (the flash drives loaded with pirated content that circulate around the island), presented as a tool Cubans rely on to escape the “endless propaganda” of state-run television. This alone tells me that the writer never actually watched it.

Most Americans who visit Cuba, in fact, don’t watch much Cuban television, or the idiot box, as my parents called it. If their Spanish is non-existent or sub-par it would be pointless, but mainly, they’re usually occupied with other things.

Before I go on, I should mention that I was allowed very little television as a child, consequently I don’t feel particularly attracted to it. But I live with someone who didn’t grow up that way, and so I’ve seen rather a lot of it here. Here are a few facts, on the house:

- Cuban television has ten channels, not six, as the article asserts (two of which are “experimental” high-definition channels that mainly broadcast movies or sports).

- Cubavision is one of those channels; it’s not a network, or a television program.

- I know a fair amount about internet watchdog groups. I would not put Freedom House in that category.

- Texting is not so expensive in Cuba that you have to turn a trick to afford it (texts are ten cents apiece), but given the writer’s repeated references to “sex workers” or prostitution in an article that is ostensibly about Cubans’ access to information, the underlying intentions and sources are clear. I could go on, but these are a few of the most obvious errors.

The main criticism of the article seems to be that Cuban television is not American television, with the suggestion that Cubans are living behind an iron curtain of disinformation that they are eager to escape and therefore, they turn to El Paquete. Actually, before El Paquete there was something known as the “antena” which is pirated satellite TV offering up the wasteland of local Miami news and Latin telenovelas. The antena still exists, but El Paquete is more like a Tivo, allowing Cubans who feel an overwhelming urge to keep up with the Kardashians or low-budget reality TV to do it on their own schedule.

And here lies the main difference between Cuban television programming and American television programming. I would say that the Cubans don’t waste time programming for the lowest common denominator. One thing that has always struck me about Cubans is how well informed they are, even (or maybe especially) those who can’t afford El Paquete. I’ve seen foreign films and documentaries on Cuban television that one would be hard pressed to find on an increasingly homogenized Netflix or Amazon Prime. Cuban news has nothing to do with the “if it bleeds, it leads” standard in the U.S. It follows an established pattern that Americans would probably appreciate, given the chance. Local, international, weather, sports, culture…plenty of culture…in that order.

The English language content on Cuban TV is not restricted to old reruns of Friends (honestly I’ve never seen Friends on Cuban TV), or heads bobbing across the screen of a film surreptitiously recorded from the back of a cinema (that’s a highlight of El Paquete, not Cuban TV). It’s far more up to date than that. When a Hollywood set designer friend came to visit he was surprised to learn that the Weeknd video he’d worked on had aired abundantly on the Cuban videoclip channel. In the U.S., he said, it was only visible on the Internet.

This raises another question. Is Cuba acquiescing to cultural imperialism? I’ve asked Cubans about that, and the general answer seems to be that trying to fill a ten channel schedule – with limited resources – while turning one’s back on the avalanche of English language content would be practically impossible. In fact, there are a fair amount of reruns. Cuba cannot survive in isolation. It might be fairer to call it engagement rather than acquiescence; at least that’s what I hope it is.

In any case, the Cubans do their best to produce their own local content, and considering the limited means, it’s not bad. One Cuban CSI-type show is based on true stories from Cuban police files, and offers a look at a side of Cuban society about which you’d otherwise hear little. The production values are decent and if you’re paying attention, the differences between Cuban policing and our own are striking. I remember one episode where a criminal running on foot from the police found himself cornered at the end of the road. I’ve never understood the instinct to flee when it almost always turns out this way. But in this case, I was shocked to see the criminal turn around and start swinging at the police with his fists. For a minute I couldn’t make sense of it, until I remembered that most police here are unarmed.

Is there ideology? Of course there’s ideology. Cuba is a socialist country. The U.S. is not. The two systems are fundamentally opposed. When I come to Cuba after a stretch up north, it’s like stepping on the other side of the mirror. I see news and commentary here that I would never see in the United States, despite the hundreds of channels with nothing on.

As for the article’s claim that the Castro regime is proudly defiant in its refusal to pay royalties, the truth of the matter is that the embargo prevents it, not the Castros. Cuban artists are also prevented from receiving royalties and the harm is arguably greater considering the comparative size of the U.S. market.

But El Paquete is wholly pirated and according to Harper’s, generates $1.5 million a week on the island. A far more interesting question is, where are the kingpins (my guess is Miami and/or Madrid), what is their cut, and why are they not being prosecuted? The Harper’s reporter doesn’t bother to dig that far; in fact no-one ever does. I wonder why?

The writer, Sue, is an American who has lived in Cuba since 2012, after visiting the island frequently for more than a decade. She publishes a blog whose name is Cuba Reality Check. She states that one of her favorite Cuban sayings is “lo que sucede conviene”, which translates roughly to “every cloud has a silver lining.”

(From Cuba Reality Check)