The smell of old books

“To put libraries in order is to exercise in a silent, modest way the art of criticism.”

Jorge Luis Borges

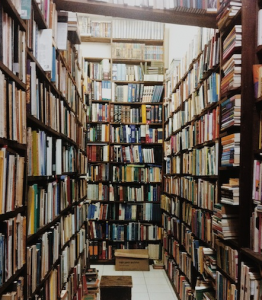

I found it almost by happenstance, because, seen from the outside, it looked like anything but a bookstore. It was lost amid some stores, amid car-repair shops and paint stores. The place looked more suitable for a robbery or drug smuggling than for thumbing through books. But I saw the sign that said “Old Books” and went in.

The door had one of those raucous sleighbells that announce the arrival of every customer and I had the feeling that I was the first person to set it off in centuries. Outside, it was hot, and while my eyes grew accustomed to the dim light indoors, I breathed that familiar smell of dampness, of an unexplored cave that I so well remembered from the old-bookshops in Havana.

This one, the one in Miami, contained all the standard clichés: it was small, and the crowded shelves formed narrow corridors through which only one person could walk. In a corner, there was a large table, suitable for reading, with books on the arts — El Bosco, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol — that nobody seemed to read anymore. Next to the door, on a desk covered with police and mystery books, rested an old computer, a 15-year-old fossil, as ancient as the rest of the place.

Sitting before it was the store owner, a woman about 60, fat, disheveled, who smelled of tobacco and kept clearing her throat. She seemed like the last survivor of a sunken ship, clinging to her books as if they were a raft.

She studied me, peering over her glasses, huge glasses that tripled the size of the words on the screen, and asked: “May I help you?”

Her voice had a slight Southern drawl, guttural, like those voices that turn raspy from lack of use and the abuse of alcohol and tobacco. I said no thanks and walked slowly, drawing one hand over the shelves.

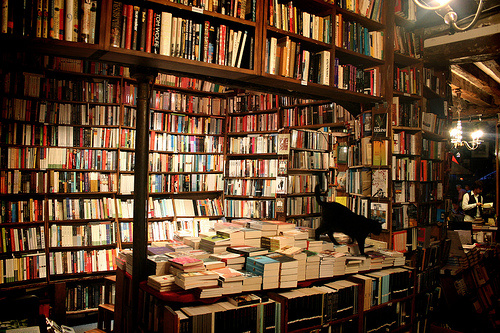

I had entered other bookstores in Miami, mostly Barnes & Noble. Bookstores whose doors slid open noiselessly, discreetly, where from the moment I entered I enjoyed the smell of recently baked pastry — yes, because they have a Starbucks coffee shop inside.

Bookstores whose every volume had been carefully classified by genre and author: Self-help, Teenagers, Science, Science fiction, Nonfiction, Law, History, Medicine, Fiction.

Bookstores whose every volume had been carefully classified by genre and author: Self-help, Teenagers, Science, Science fiction, Nonfiction, Law, History, Medicine, Fiction.

Bookstores where, if you felt lazy, you could ask a clerk to find your book in the database and, if it wasn’t, you could order it and have it mailed to your home. Bookstores that had an entire department for kids and another one for nerds, with games, action figures and comics.

Bookstores, in sum, where you would love to live, even if in a corner, in the best-sellers section.

How has this hovel survived amid so much implacable competition? I thought, as I wended my way through the aisles, looking like an explorer in the jungle. Many of the books were cheaply bound, with cardboard covers, but there were also some bound in leather, with the thread visible under the spine, like the most prized books at the Plaza de Armas in Old Havana, though these didn’t cost the equivalent of a month’s salary.

I read some names at random: Rabelais, Cervantes, Chekhov, Stendhal, Poe, Balzac, Whitman, Becquer, Twain, Borges. In another shelf I found a large collection of religious books, where the Koran rested next to the Mahavamsa and the Judaic Bible. There didn’t appear to be any classification system; if there was, it wasn’t even alphabetical.

But that’s just what’s so thrilling about going through a rare-book store: the uncertainty, the possibility that, somewhere in those shelves, unannounced, is the book you’ve been searching for all your life.

I didn’t find it there that day, but I did discover, on the shelf for Spanish-language books, an entire collection of titles that in Cuba some call banned and others, more moderate, call hard to find. Titles that you have always heard from third parties, books that if they ever fell in their hands it was because they were lent by a friend, who borrowed them from another friend, who had never returned them to their original owner.

There I found, to mention a few, “Fuera de Juego,” by Heberto Padilla, “Antes que Anochezca,” by Reinaldo Arenas — a book absolutely over-rated, perhaps because of the morbosity caused by Arenas’ dual status (homosexual and outcast), but not at all worthy of the fame it enjoys — and “La Habana para un Infante Difunto,” by Guillermo Cabrera Infante [These books have been translated into English with the following titles: “Out of the Game,” “Before Night Falls,” and “Infante’s Inferno,” respectively.].

I could have filched any one — after her routine greeting, the woman paid no attention to me, even though I was the only customer. But I’ve never stolen a book in my life; I lack the skill and the nerve. Besides, the prices were more than reasonable. I took “La Habana” — maybe because I wanted to lick the nostalgia — and walked over to the woman’s desk.

We chatted while she made out the bill. Her name was Mary Ann and she had owned the store for years. I told her that I was Cuban and spoke a bit about Cabrera Infante. She nodded, condescendingly, but it was evident that she wasn’t interested. Her thing was the thrillers and the police novels she had on the bureau, the only books she had organized with care.

She named authors that I had never heard of, whose books I’ll probably never read. Then, when she realized that the conversation was going nowhere, she asked: “Do you have a computer with Internet access?”

I nodded yes.

“Well, the next time don’t trouble to come. Go online and send me your order by computer,” and she pointed to the dust-covered dinosaur before her, “and I’ll mail it to your home. That’s how I make most of my sales.”

I didn’t know it then, but later I learned that a whole network of old and used books exists in Florida and they use the same system. They even have a society — Florida Antiquarian Booksellers Association, founded in 1981 — that every year stages an old-book fair. Perhaps thanks to their cohesion they’ve lasted for so long.

Roberto Bolaño said that we all have the bookstore we deserve, except those who have none. This one, a bookstore that survives in the middle of nowhere, that smells of dust, obstinacy and solitude, that has an owner with a cigarette voice who adapts and sells old books via the Internet at the speed of a Jurassic-age computer, this one, I thought, just might be mine.