Salón Tropical: A restaurant still afloat

Norges C. Rodríguez Almiñan

SANTIAGO DE CUBA — In 1996, the Cuban government decided to allow some economic activities theretofore exclusively handled by the State to be developed by private workers or self-employed entrepreneurs.

Among the activities allowed, one of the most popular was the preparation and commercialization of food. The places where this activity was carried out became known as “paladares,” thanks to a Brazilian soap opera broadcast on Cuban TV at the time.

During that period, the opening was very timid. The State restricted the number of customers (only 12 at a time) and the hiring of the labor force, stating that only relatives living on the premises could work in the restaurant.

In the early 2000s, the government took several measures that adversely affected the private workers and many of them gave up their work licenses. In 2011, the regulations on private workers were relaxed and self-employed entrepreneurs again became actors of importance in the country’s economy.

One of the private restaurants that survived all these waves, one of the oldest in Santiago de Cuba, is the Salón Tropical in the November 30 neighborhood, known to everyone as “the paladar in the 30th.” Its owner, Nilda Gil, has managed the place from the start, as best as the rules of the game allowed her.

Norges Carlos Rodríguez: When did you found the restaurant and why did you choose that activity and no other, like lodging for instance?

Nilda Gil: In March 1996. I began with this because, although I never studied food preparation, I always liked it. Lodging did not attract me. At first, I worked and my sister took care of the kitchen. When I returned from work, I’d remove my uniform and helped her in the kitchen. We began with a small seating capacity. I used the first room in the house and began with four tables and six chairs.

NCR: How did you handle the hiring of workers, the preparation of the menu, and how did the customers behave?

NG: At that time we couldn’t hire workers, only members of the family who had to live in the same house, and were members of the same CDR [Committee for the Defense of the Revolution, a neighborhood watch network]. The menu consisted of spaghetti, pork chops, smoked loin, and lamb, which were the only things we could sell. Seafood could not be sold; it was banned. I had to reinvent and lay out different menus for three days with the same ingredients: pork, lamb, rabbit and chicken. One day we’d make Italian food, the next day Chinese. At the time, many customers came, both Cuban and foreign. There were a lot more customers than today.

NCR: The Cuban government has acknowledged that the 1996 opening was done as a palliative. It assumed that self-employed work was a necessary evil. This made many people look at self-employed workers with suspicion, and many prejudices were formed regarding you. What experiences did you have with this?

NG: All kinds. I was inspected three times over the sale of lobster and shrimp, which were forbidden. I was detained by the police. If anything was missing at some state-run place, they’d come here, looking for it. The inspectors came day in, day out. We could barely work.

NCR: When did the taxes go up and by how much?

NG: That was in 2000. At first, we all paid the same: 500 national pesos [CUP]. Then someone did a study and said that some paladares should have their taxes raised because of their location. Those that were in midtown should pay in CUC [convertible pesos]; those that weren’t, would continue to pay in domestic currency.

I had to pay in domestic currency but that problem was that I was situated in a neighborhood with many boarding houses. So I asked the ONAT [internal revenue office] to do a study and give me a license for hard-currency trade, so I could serve foreign tourists, because I couldn’t do business in hard currency if I didn’t pay taxes in hard currency. At the end, I had to pay 700 CUC [about $700]; restaurants in midtown had to pay 860 CUC.

When the taxes went up, many paladares in Santiago de Cuba disappeared. From the existing 120 paladares, only eight remained, then only two, Las Gallegas and the Salón Tropical. The customers either came here or went there.

NCR: Why do you think the taxes went up?

NG: Well, remember that this was a necessary evil and people knew that self-employed workers worked here.

NR: In 2011, new activities were approved. In the case of restaurants, the state allowed an increase in the number of chairs and allowed you to hire workers from outside the family. What benefit did those changes bring?

NG: Those measures were very favorable because in the past only the relatives could work in the business, and that entailed problems with discipline. Now we have the possibility to hire specialized personnel who know the trade.

Now we notice a slight change. In the past, we self-employed workers were almost accused of being counter-revolutionaries; now, we’re described as the rescuers of the nation. I don’t know what we’ll be tomorrow, but I do notice a tendency to help us. We’ll see.

NR: In comparison with 1996, how’s the attendance and the access to supplies and foodstuff?

NG: The clientele has shrunk a lot. In the past, we started work at noon and worked till night. Today, we have very few customers at noon, and only at night can we do something. The subject of supplies and foodstuffs is tough on us. It was as difficult in ’96 as it is today. We don’t have a market that can supply us, so we have to buy the food at the hard-currency stores — that’s expensive.

NR: One of the changes forecast for the country is the opening of wholesale markets. What do you think?

NG: I won’t believe it until I see it. I’ve been waiting 17 years for that.

NR: One of the options in this new opening is a link between private businesses and state-run enterprises. What do you think of that?

NG: Well, I’ve already gone through that and didn’t fare well at all. I had a contract with Oriente University that was not favorable to me. I always abided by the contract but they didn’t, so there were past-due bills that they never paid.

NR: Many private businesses in Cuba are taking seriously the role of advertising and marketing, especially on the Internet. What do you think of this? Is it important to you? Have you delved into it?

NG: That’s extremely important and, yes, I have delved into it. I’ve appeared in the magazine Excelencias Gourmet, in the issue published for the Caribbean Festival, and that helped a lot because many tourists and participants in the festival came to dine here.

The Gourmet television network, which broadcasts to Latin America and the United States, did a documentary on us, too. They filmed an ordinary day in the paladar: how we go to the store, how we shop in the market, our day’s work until the closing at night. It was a very pleasant experience.

As a result, I received customers from Uruguay and Argentina. We also have a presence on the Internet. The restaurant’s Web page is updated regularly. We have a profile in Tripadvisor, a page in Facebook and one in Twitter.

NR: What personalities have you hosted?

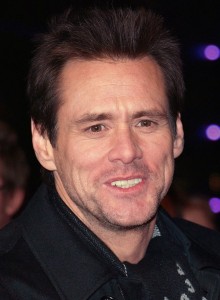

NG: Actor Jim Carrey came here, also many Cuban actors and many diplomats. We’ve had SINA officials [U.S. Interests Section], and the French ambassador. The musicians in the Charanga Habanera came and I had to roast a ham for them. We also had [Cuban actress] Luisa María Jiménez and others who I don’t remember.

NR: Today, American tourists cannot come to Cuba because of the restrictions imposed by Washington. What benefits do you expect for your business if the laws that prohibit the travel of U.S. tourists to Cuba are lifted?

NG: It would be very beneficial, because I know that many would come. This city would fill with them, and that’s beneficial not only for self-employed entrepreneurs but also for the country at large.

The author is an engineer living in Santiago de Cuba. He hosts the blog ‘Salir a la manigua,’ where this interview first appeared. Progreso Weekly has published an abridged version.

(From Salir a la Manigua)