A Republican joins Obama in seeking ties to Cuba

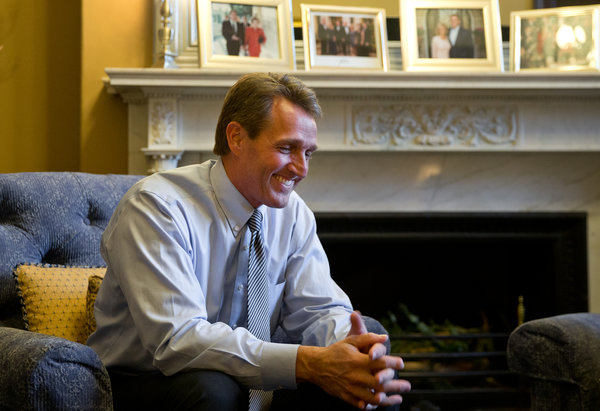

WASHINGTON — Two days before President Obama ended a half-century of diplomatic estrangement with Cuba, his national security adviser, Susan E. Rice, asked Senator Jeff Flake of Arizona to be the only Republican on a secret flight to Havana to bring home a jailed American, Alan P. Gross — and to tell no one.

“I felt like I was in a Tom Clancy novel,” Mr. Flake said.

Now Mr. Flake, who has spent a decade in a lonely battle against his party to push for easing restrictions on Cuba, is the chief Republican defender of the new Obama policy. White House officials are counting on him to make their case to his party’s rank and file, even as Republican leaders and Cuban-American lawmakers, like Senator Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida, threaten to keep the president from appointing an ambassador or funding an embassy in Havana.

At a Capitol Hill hearing presided over by Mr. Rubio on Tuesday, the two men sat next to each other, somewhat awkwardly, as Mr. Rubio grilled administration officials on a policy he has called a “concession to tyranny.” But even before the hearing, Mr. Flake had moved ahead: Last week he filed a bill to end the decades-old ban on American travel to the Communist island nation.

It is an unlikely role for the deeply conservative senator, who also broke with Republicans on immigration. Then again, Mr. Flake is nothing if not persistent.

His last big bipartisan endeavor was spending a week on a one-episode television reality show, “Rival Survival,” with Senator Martin Heinrich, Democrat of New Mexico, on the remote Pacific island of Eru, in the Marshall Islands. The two swam in waters filled with sharks and venomous stonefish, ate raw clams and tried but failed to make fire.

Their Senate colleagues at first thought it was a hoax. “They thought it was an Onion article,” Mr. Heinrich said.

Back in the relatively real world of Washington, six Republicans joined Mr. Flake in signing a letter to the White House backing expanded trade and travel with Cuba. In an interview, Ms. Rice called the Flake bill “an important step” and described Mr. Flake as a “discreet and genial” partner on Cuba strategy.

Mr. Flake’s Cuba critics are exasperated. “I can’t quite figure out what drives him,” said Senator Robert Menendez of New Jersey, the Senate’s only Cuban-American Democrat.

What drives him, Mr. Flake said, is his belief that the United States government should not infringe on Americans’ right to travel. He has visited Cuba nine times, including a November trip to see Mr. Gross when he was in jail and ailing. “It’s a freedom issue,” Mr. Flake said.

A descendant of Mormon pioneers who grew up in a family of 11 children on a cattle ranch in a small Arizona town, Snowflake (named for his ancestors), Mr. Flake, 52, is mild mannered and has a wry sense of humor. He admits he is an unlikely figure in the Cuba debate. “I took a poll of Cuban-Americans in Arizona,” he said, deadpan, “and both of them said, ‘Go ahead.’ ”

His path to the issue was circuitous. As a Mormon missionary in Zimbabwe and South Africa, Mr. Flake learned to speak Afrikaans, a skill that later landed him a job in Namibia, running a foundation devoted to democracy. There he encountered the Cuban military, which played a role in Namibia’s move toward independence.

In 2000, after running the Goldwater Institute, a libertarian-leaning research organization, Mr. Flake was elected to the House, where he founded the Cuba Working Group with a Democrat, Bill Delahunt, then representing Massachusetts, and tried to loosen restrictions on Cuba. But he was outmaneuvered, he said, by hard-line Cuban-American colleagues.

His trips to the island, meanwhile, deeply affected him. Mr. Flake recalled one visit to a Havana cemetery with a son of Cuban exiles who had never seen his brother’s grave. He came home “thinking what a crazy policy this was.”

Phil Peters, a Cuba expert who traveled with Mr. Flake, remembers a long taxi ride to a tiny Mormon congregation that held services in a Baptist church. Mr. Flake addressed the congregation, and Mr. Peters translated his words into Spanish. “It was very moving,” Mr. Peters said.

There were upsetting moments as well: In 2003, Mr. Flake and other lawmakers had breakfast with dissidents, who were later rounded up and jailed.

In the Senate, Mr. Heinrich, Mr. Flake’s partner in the Pacific island escapade, speaks for many of Mr. Flake’s colleagues when he calls him “straightforward and trustworthy.” But Mr. Flake infuriates those who accuse him of pandering to the Castro brothers, Fidel and Raúl, and ignoring human rights abuses in Cuba.

“I’ve been telling him for years, he’s a very nice man, but he’s mistaken about Cuba,” said Frank Calzon, executive director of the Center for a Free Cuba, an advocacy group.

Mr. Flake says he is hardly ignoring Cuba’s failings, but wants to expose them by opening the island to more Americans: “We’ve got a museum of socialism 90 miles from our shore.” Conservatives, he said, ought to want Americans to see it.

But Mr. Flake has drawn at least one careful line in his advocacy. When Fidel Castro hosted an extravagant dinner for visiting American lawmakers, his wife went, but Mr. Flake, then a House member, stayed in the hotel. “I didn’t want people to think, ‘Oh, you’re just going down there to be feted by Castro’ — this kind of hero worship thing,” he said.

Mr. Flake has met with President Raúl Castro; he pressed for Mr. Gross’s release and tried to prod Mr. Castro to officially recognize the Mormon Church.

So far, Mr. Castro has not. “But he was a lot more forthcoming with Jeff than I expected,” said Senator Patrick J. Leahy, a Vermont Democrat, who was there.

Mr. Flake recalls Mr. Castro’s blunt greeting to him: “Where’s the Mormon?”

In November, Mr. Flake and Senator Tom Udall, Democrat of New Mexico, met with Mr. Gross, who was despondent and “had already said he had spent his last birthday in prison,” Mr. Flake recalled. Then, he said, he visited Ms. Rice in her West Wing office and presented her with a list of steps the president could take, using his executive authority. “And I said, if there are negotiations going on with Alan Gross, I don’t want to know about it.”

In fact, Ms. Rice said, the deal to release Mr. Gross, in a complicated prisoner swap negotiated with the help of the Vatican, had already been set. Less than a week later, she called Mr. Flake and asked him to get on the plane. The senator texted his wife, telling her he would be home later than planned.

(From: The New York Times)