Plan B: College grads in the private sector

Melissa studied for six years for her degree in Foreign Languages but never practiced her major in a state-run center. She knew that her wages — less than 20 convertible pesos (20 dollars) a month — would not be enough to live on. She put away the newly printed diploma and sought employment in a private restaurant. It needed tall, “good-looking” girls and her college presence got her the job.

At home, she was not alone in making that decision. Her husband, Fabio, a metallurgical engineer who graduated from the José Antonio Echeverría Polytechnic Institute, left the research center where he had been placed and got a job in a 3-D cinema. A few weeks later, the Cuban government shut down all such installations.

Five months after losing his job, Fabio became a clerk at a cafeteria. In less time than he imagined, the coffee shop went bankrupt and the engineer decided to try another unique trade. Today, Fabio is an itinerant vendor of “the weekly package,” a rented collection of video entertainment.

Five months after losing his job, Fabio became a clerk at a cafeteria. In less time than he imagined, the coffee shop went bankrupt and the engineer decided to try another unique trade. Today, Fabio is an itinerant vendor of “the weekly package,” a rented collection of video entertainment.

To leave a profession achieved after years of study and enter another was not easy for the couple, but they did it as their Plan B, to be followed when circumstances demanded a radical change.

‘Enlightened unemployment’

That’s what Cuban social researchers call the job migration of university-trained professionals to less-qualified trades and jobs. With the relaunching of the non-state sector in 2011, this phenomenon re-enters the debate.

“There is a tendency for employers to hire very young personnel that usually comes from another sector,” says Mayrín, a Havana resident who created an employment agency for private business. “Also, the employers ask that the job-seeker speak some basic English, especially in restaurants and rented homes, which are the spaces that need workers the most.”

[Editor’s Note: Surnames not published at the request of the interviewee.]

“I remember a small carpentry shop that asked me for a clerk,” she said. “They wanted someone with a university diploma, an English-speaker with knowledge of accounting, a good education, good communication skills, good looks, no older than 35. I find it difficult to place people older than 40 with less than a high-school diploma.”

“I prefer university graduates so they can have a good background in anything they do, whatever it is,” says Rolando, the owner of a restaurant on Galiano Street. As waiters in his establishment he hired an industrial engineer, a graduate in economics, a graduate in accounting, and a graduate in socio-cultural studies. He expects he will hire several other degree holders when he opens franchises in other parts of the capital.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to find specific data about the drift of young job-seekers to the non-state sector. Not even the social scientists have sufficient statistics to describe it as a trend.

“You can’t say that now is the time when young professionals are looking at other, more attractive jobs,” says Idania Rego Espinosa, of the Center for Psychological and Sociological Research (CIPS). “Since the 1990s, many college graduates have migrated to tourism and foreign companies. Now, new options open up and young people with those qualifications are best prepared to compete in the job market,” she says.

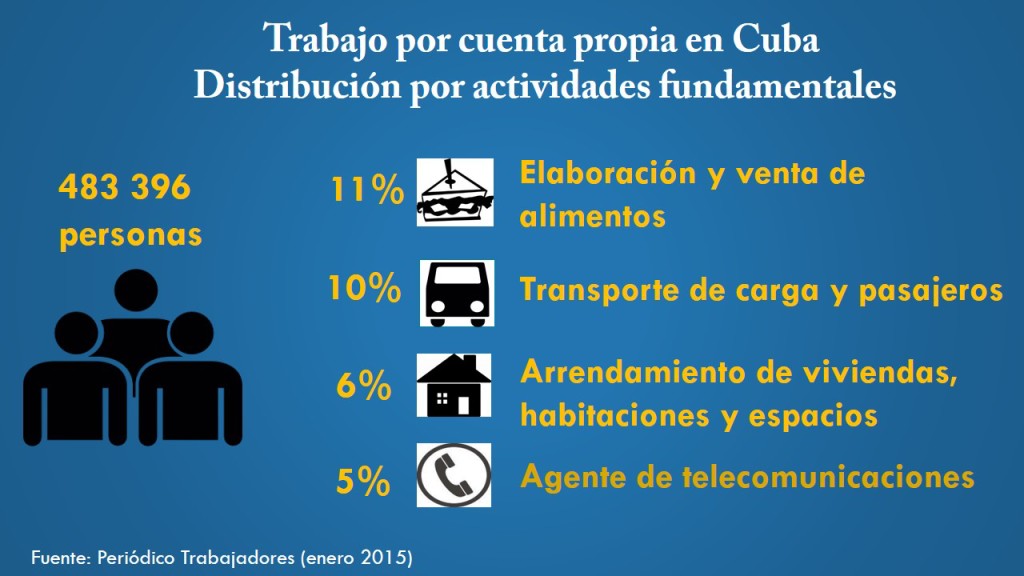

Almost half a million licenses for private employment in a job market of 5.22 million people is not a very significant figure. Therefore, not many young professionals choose the non-state (private) sector as their immediate solution, compared with those who stick to activities linked with their training.

“In my field, the most I could do is repair personal computers or cell phones,” says Claudia, a telecommunications engineer. “That could be useful and interesting, but it doesn’t attract me because I don’t see any professional development, just a mechanical, repetitive chore that requires knowledge but only up to a point.”

“Self-employment is not conceived as a function of human capital because the college graduates don’t find activities that suit their training,” says Rego Espinosa. “However, if I don’t have a way to get a job thanks to my college education but need to live better and earn more money, I’ll simply work for a self-employed entrepreneur.”

That is a reaffirmation of what academicians like Ricardo Torres, of the Center for Cuban Economic Research, have called one of the biggest contradictions of the socialist model — high efficiency in the creation of human potential vis-à-vis a system that’s incapable of generating opportunities so it may take full advantage of that potential.

That’s the question heard most often from many who bet on spaces not under state tutelage. To the youngest job seekers, that attitude begins when they look at their parents and more experienced colleagues.

“People who had spent 30 years in my research center were still at the same level as I, the newly hired, was,” Fabio recalls. “And I said to myself, ‘Where am I going to be in 30 more years if I don’t gain any human comforts?'”

Psychologist Rego hears that same reasoning during her field research.

“Sometimes, the young people point to their elders, who work in the state-run sector. ‘My parents have college degrees, and after so many years, look at the salary they earn!’ they tell me. And, of course, they change their expectations.”

“It bothers me that a professional has to ‘find a way’ because the wages are not enough,” confesses Grettel, a full-time biologist who teaches math at home, after work. “It’s not right that I should be a private tutor or that my friends should do nails or sell candy when we’re in fact scientists.”

“I always liked to work for a few people, to own my time,” says Damián, an architect who left his job in a large construction firm and partnered with a colleague to set up an unlicensed company. “I think that almost all of us want to stay in our profession, because that’s what we studied and that’s what we like, but I’m willing to reconsider it if I feel that I’m wasting my time.”

The feeling of loss can be experienced when self-employed entrepreneurs tally their income at the end of the month. According to the latest public information, the average state wage is 471 Cuban pesos a month (about 25 dollars) while the minimum monthly income declared by private workers is about 1,500 Cuban pesos, three times that figure.

“There is a ‘silent generation’ that doesn’t appear in the statistics, whose opinions we cannot share. It’s the young people who emigrate,” says Mirlena Rojas, of the group of Labor/Social Studies at the CIPS.

An annual migratory deficit of more than 40,000 people — mostly 20 to 40 years old — impacts silently but directly on the erosion of the domestic social fabric and therefore on the qualified labor force, which is the country’s basic asset.

“I have a friend who opened an ice-cream store, sold it right away and spent the money in Brazil, getting her master’s degree,” says Claudia. To slow down the exodus, almost everyone is asking for an urgent transformation of the rules of the economy.

“Today in Cuba, you find someone who gets three jobs in his own specialty, or has a job and finds another, but doesn’t believe that going into food service is the solution,” opines Isabel Moya, editor of the Women’s Publishing House. “Then there are those who do take up that way of life. You have to look closely and respect people’s individual aspirations. Don’t demonize them.”

Their existence posits the need to ease access to employment for thousands of university graduates who still haven’t emigrated, thus improving the outlook for state-run businesses in the country.

Not waiting for that to happen, Melissa quit restaurant work and got a job at a private English language school. She returned to her chosen field of work and says she feels comfortable with her new boss, although she fears a sudden change in the employment laws.

Fabio would like to return to metallurgy but sees that possibility as very distant. For now, he is at ease distributing “the weekly package” while going ahead with his Plan B.

Photos: Alejandro Ulloa

Progreso Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists so long as source and author are identified.