Mandela: Bending the arc of history

Writing about Nelson Mandela is a daunting task. It’s not just the greatness of the man or the fact that so much already has been written — I found 810 million entries in a search of Google news — about the liberator and founder of the modern, democratic, multiracial South African state. It is also that it hard to do justice to the singular accomplishments of this man his countrymen affectionately called Madiba.

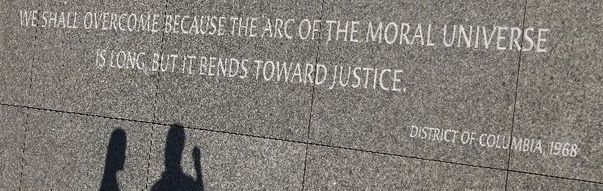

Martin Luther King once said that while the arc of history is long, it bends toward justice. The bend in that arc is not a fact of nature. It is accomplished through the struggles, sacrifice and commitment of men and women who abhor injustice. Yet there are few if any instances in history in which one human being so successfully bent the arc of history so that it would move toward justice faster and arrive at it with less trauma than anybody could have imagined.

When I was a sociology student in college and graduate school eons ago the apartheid regime held all power over the vast black majority through institutionalized violence in all its forms, from murder and imprisonment to a humiliating system of passes and residential controls that transformed the African people into aliens in their own land.

Almost all my peers and professors thought the outcome of this fight between a black majority that militantly refused to submit to the brazen oppression of apartheid and a recalcitrant racist regime with a formidable military and security apparatus could inevitably end in tragedy. One scenario envisioned an increasingly threatened regime inflicting escalating levels of violence upon the black masses until they submitted or were subjected to genocide. The other possible outcome was for the black majority to somehow wrest power from the whites through the ballot or the bullet and then exact a vengeance proportional to the injury, driving the whites out of the country or massacring them.

That both of these horrible but probable trajectories were averted was due almost entirely to one man, Nelson Mandela. His political will and strategic vision, his capacity to endure twenty-seven years in a harsh prison and emerge unbroken, determined as ever to destroy apartheid and install democracy but also to seek racial reconciliation, broke the back of apartheid and spared South Africa a bloodbath. No one else could have pulled it off. It was an early example of a pair of traits that very rarely coexist but that Mandela possessed in abundance: an iron-clad political will and an astounding capacity for forgiveness.

Others deserve some credit too, of course. South African president Willem de Klerk, with whom Mandela shared a Nobel Peace prize, had the courage to finally free Mandela and to negotiate the end of apartheid. Stephen Biko, the young anti-apartheid leader murdered by the regime in 1977, the hundreds of students killed in the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, and countless, nameless others who gave their lives for the cause deserve even more credit. Credit is also due to the thousands of students and activists in the United States and Europe who protested and campaigned tirelessly against apartheid.

Only the very embittered or uninformed would deny that Fidel Castro and the Cuban soldiers who fought and defeated the vaunted South African army and its black proxies also played a major, perhaps decisive role in convincing the white South African leadership that the road of endless intransigence was a dead end. In the absence of the Cuban military forces the South Africans in all likelihood would have succeeded in creating puppet states all around their northern border to serve as buffers preventing anti-apartheid guerrillas from infiltrating the country.

The Cuban defeat of the South African army in Angola sapped the morale and confidence of apartheid supporters. Even somebody as obsessively anti-Castro as Carlos Alberto Montaner recognized in a recent Miami Herald column that “to Mandela, or to anyone with a skin hardened by truncheon blows and prison life, for a remote country like Cuba, ruled by a white man, to send hundreds of thousands of soldiers to fight for 14 consecutive years against the interests of South Africa, and sometimes against that country’s army, was something that called for gratitude.”

Indeed. While Montaner predictably and unpersuasively imputes Machiavellian motives for Castro’s decision to send Cuban troops to foil the apartheid regime’s grand strategy, these facts are clear. The Cuban government supported the right side in the South African struggle, for a long time and at incredible cost in lives and resources. In contrast, for most of the conflict the United States backed the wrong side militarily, economically, and diplomatically, an important additional factor in understanding Mandela’s gratitude to Castro, one which Montaner conveniently fails to mention.

Montaner also fails to allude to the shameful way key Cuban-American political leaders in Miami embarrassed themselves and the city when they tried to snub Mandela during the latter’s brief stop here in 1990. The spectacle of a two-bit politician like then-City of Miami Mayor Xavier L. Suarez — a man so daffy he believes the theory of evolution is bogus — lecturing a political giant like Mandela would be comical if the result had not been a ramping up of already high Cuban-black tensions. For his part, Mandela completely ignored all the sound and fury signifying nothing except demagoguery.

Mandela, of course, was not infallible. Like every human being, he made mistakes. His most serious one was failing to recognize early enough the scourge AIDS would become for South Africa.

Worse than the tendency to posthumously turn Mandela the man into Saint Mandela is the effort to defang the tiger, to present a Mandela palatable to all political persuasions, to construct a narrative of his life that omits inconvenient stances like his unstinting support for the Palestinian cause, his tough criticism of the Iraq war and of the U.S. role in the world in general, and his abhorrence of economic inequality. Better to remember the complete man, tough and kind, idealistic and pragmatic, a progressive and a democrat, a giant but not a god.