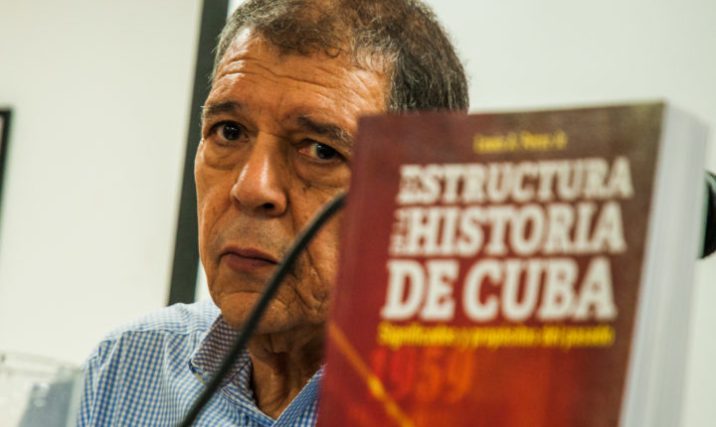

Photo of Louis Perez Jr. by Istvan Ojeda Bello

Photo of Louis Perez Jr. by Istvan Ojeda Bello

Louis A. Pérez Jr.: In search of the enigma of being Cuban

HAVANA – This time I did not miss the opportunity to meet Louis A. Pérez Jr. (New York, 1943), whose investigative work of more than 30 years has been recently released to the Cuban public.

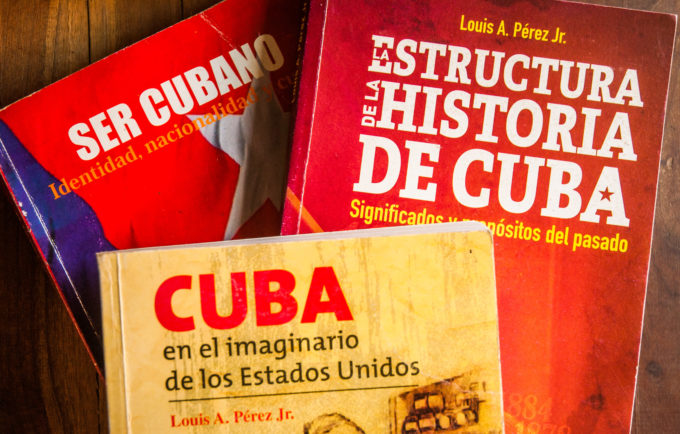

The author of a beloved book, “On Becoming Cuban. Identity, nationality and culture”, was in Havana recently to present another of his books, this one first published in 2013, “The Structure of Cuban history. Meanings and Purpose of the Past.” With the UNEAC’s Sala Villena auditorium to ourselves, we were able to exchange some impressions.

The two books mentioned, together with “Cuba in the American Imagination” (2008), have been slow in coming.

Dr. J. Carlyle Sitterson, of the Department of History of the Institute for the Study of the Americas, Hamilton Hall Gobal Education Center of Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina, explained during the presentation of Perez’ third translated work, that “The structure …” is not so much about “a history of Cuba as about reflections on it, its future, its contours and its consequences; about the capacity of the past to shape the character of a people .”

“This is the book we need,” said Dr. Eduardo Torres Cuevas, president of the Academy of History of Cuba, and added that this is an opportunity that must not be wasted because it deals with the fact that “we are in bad times, where many believe that History is not necessary, but for us it is because history has not ended.”

Ojeda Bello (OB): In your work there is a recurring theme of being Cuban, and the depth of American influence in the country. Where does that interest come from?

Louis A. Perez Jr. (LAP): I started with the idea of national identity and that is how it is in the book “Being Cuban …”, but over the years I came to the point of view that there was no identity in the singular, but rather there were identities that changed through time — different cultures. More than national identity, it is about national character, which is not the same. Because we have to talk about the national character, the idiosyncrasies, the modes of behavior, of acting. That is what makes the Cuban people different from the other peoples of the world.

To talk about the character of the Cuban people, we must understand the history of Cuba, how the Cuban conscience was formed, how the consciousness of the Cuban nationality was formed. What I defend in “The Structure …” is that the Cuban people were formed under terrible conditions, almost half a century of struggle, in which thousands and thousands of people perished, and that had a very profound impact on the national character of its people.

OB: In spite of this, and although they are well informed, it seems that U.S. politicians have never understood how Cubans work and think …

LAP: The truth is that Americans understand very few peoples; it is not only Cuba. The problem is that Cubans are also obsessed with the United States, who have their moment of obsession with Cuba, but for the Americans, Cuba is like a shooting star that passes in the night, illuminates, and returns to darkness.

In other words, Cuba has been an obsession for the United States since the time of Jefferson. It has always been said that, because of the economy, the investments, but it really has to do with the concept of national security of the U.S. For Americans, since the nineteenth century, since they took possession of Louisiana and Florida, Cuba was presented as its southern border, the egress and entry to the Gulf of Mexico. From that moment on, it was a strategic point for them and it entered into the American mindset that Cuba was going to be their possession.

OB: Isn’t there some pride involved? Because Cuba has been a pending cause for many years.

OB: Isn’t there some pride involved? Because Cuba has been a pending cause for many years.

LAP: Not that much. For the Americans, Cuba is a dependency, it must be a dependency. The Sandinistas, the Soviet Union and the socialist bloc have already disappeared. [The U.S.] has normal relations with Viet Nam and China. Everyone was sure that when the USSR fell, Cuba would too, and it did not collapse. They have no explanation for that. They still want to own Cuba as they did in the nineteenth century.

OB: Your thesis provokes me to think of examples like when on July 27, 1953, just at the most inappropriate moment because he had just been arrested, Fidel Castro argues with the soldiers saying that they, the assailants to the Moncada barracks, were the followers of the Mambí army, while the Batista soldiers were the continuators of the colonialist army.

LAP: Fidel Castro was a good historian who knew his history, his people. If you read his speeches during the first months of 1959, everything has to do with history. His politics had to do with the past, and that resonated throughout the country because the people already had a deep knowledge of their own history. When in Santiago de Cuba, on January 1, 1959, he said that “the work of the Mambises will be fulfilled,” the people knew what he was saying, they understood him perfectly and without need for further explanations; Americans, I doubt it.

OB: Another thing I must ask is your assertion that “for a long time Cubans have contemplated the meaning of national character; sometimes with exaggerated claims of exceptionalism.”

LAP: (Laughing) “Ah, Cuban vanity! And the funny thing is that both countries have that in common, they think they are exceptional countries. Americans, of course, and Cubans too.”

OB: This is very noticeable when talking to other Latin Americans who have a different relationship with the United States. Does this mean that the relationship can be seen with more objectivity or moderation?

LAP: Forget about it! I once met a fiercely anti-Castro family who privately confessed their pride in the role of Cuba in the Angolan war, and how it defeated the South Africans who were supported by the Americans.

The value of what Cuba did goes far beyond that, it goes to Latin America. Before 1959, studies on Latin America did not exist in the United States. Onward from January 1 is when they started studying [their southern neighbors] because it reached the level of national security, because it was necessary to contain the “virus” of communism.

OB: How does it feel to see that your work is studied more naturally in Cuba?

LAP: I am very happy that it is being read and that it is generating debate about ‘Being Cuban …’

OB: Perhaps the greatest value of ‘Being Cuban’ is that it goes against the historical schemes and against the convenience of binary codes …

LAP: Everything comes through the culture. In a certain sense the U.S. recognizes the Cuban because there are elements in the Cuban character, and some idiosyncrasies, that come out of the American culture. They know each other, there is a sympathy from people to people because there is something mysterious in the air that makes them known. Both sides are fans of baseball, boxing, and that has deep roots. Many people do not support baseball, but among Cubans and Americans there is delirium for that sport. There are whole generations that grew up with the cowboy films. That had an impact.

OB: It still has it, in music, in the television shows.

LAP: It is a sensitivity of both peoples.

OB: In this, there could be a way for us to understand each other…

LAP: Of course! I was amazed at how the musical group from the Buena Vista Social Club, by then old and retired, successfully toured the United States.

OB: Yes, but that goes back to the theme that they continue to sell that Cuba is a country stopped in time, and Buena Vista Social Club fitted that vision very well.

LAP: Surely. What I propose in my article, The Politics of Compromise, known as “people to people,” urges you to visit Cuba before it changes. The fact is that it is not Cuba that has been frozen in time, it is American thought that has been frozen over time.