Lawyers should keep their eyes on Cuba sanctions cases

By Peter “Bo” Rutledge, Katherine M. Larsen and Miles S. Porter / Law.com

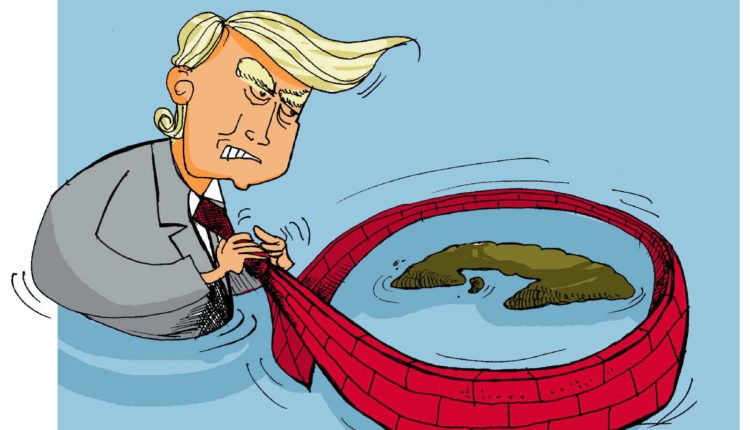

A dramatic change in the executive branch position on Cuban sanctions recently led to a wave of litigation in the federal courts and could have broad implications for entities that conduct business in or with Cuba. In April, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced that Title III of the Helms-Burton Act would no longer be suspended, thereby allowing U.S. nationals to file lawsuits against any individual or entity that “traffics” in property expropriated by the Cuban government.

The Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity (LIBERTAD) Act of 1996, also known as the Helms-Burton Act, bolstered the robust U.S. sanctions on Cuba. It sought to discourage foreign investment by prohibiting the indirect financing of transactions involving property confiscated from U.S. nationals. One of the main purposes of the act is to “protect United States nationals against confiscatory takings and the wrongful trafficking in property confiscated by the Castro regime.” Title III of the Helms-Burton Act establishes a private right of action for U.S. nationals against entities trafficking in property expropriated by the Cuban government since 1959. Title III defines “trafficking” broadly, imposing liability on individuals or businesses who “knowingly and intentionally” sell, transfer, dispose of or engage “in commercial activity, without the authorization of a U.S. national with a claim to the property.” In addition, Helms-Burton authorizes the president to suspend the right to file a lawsuit for successive six-month periods, thereby foreclosing U.S. nationals’ ability to seek damages for expropriated property. Until Pompeo’s April announcement, Title III had been suspended by successive administrations and had lain dormant.

The international reaction to the suspension of Title III has largely been negative. The decision by the Trump administration has been condemned by significant U.S. trading partners, including the European Union, Japan, the United Kingdom and Canada. The EU has issued a statement expressing strong opposition to the suspension, claiming the measure is contrary to international law, and they will consider all options to protect its legitimate interests.

On May 2, the first lawsuit was filed under the Helms-Burton Act. Javier Garcia-Bengochea brought an action under Helms-Burton as the rightful owner of an 82.5% interest in commercial waterfront real property in the Port of Santiago de Cuba. Garcia-Bengochea alleges that, in 1960, the Cuban government nationalized and expropriated said waterfront property without compensation. Garcia-Bengochea’s ownership consisted in part of a claim certified by the Foreign Claims Settlement Commission, as well as an uncertified claim in part. Garcia-Bengochea alleges that defendant Carnival Corp.’s actions constituted “trafficking” when Carnival knowingly and intentionally commenced and promoted its commercial cruise line business to Cuba, in which Carnival regularly embarks and disembarks its passengers using the commercial waterfront real property. Carnival Corp. filed a motion to dismiss, alleging that Garcia-Bengochea’s claim was barred by Title III’s “lawful travel” exception, that Garcia-Bengochea failed to prove a rightful ownership claim to the property and that the alleged property is not the property Carnival is allegedly trafficking in.

The District Court for the Southern District of Florida, denied Carnival’s motion to dismiss, held, that based on the text, context, and purpose of Helms-Burton, Garcia-Bengochea’s complaint adequately alleged ownership of the property in question. The court reasoned that Congress would have understood the term “claim” to confiscated property to encompass both direct and indirect interests, as a more limited reading would significantly undermine the Congressional goal of deterring trafficking. The court’s decision indicated that as long as a plaintiff is able to show some type of beneficial ownership, the claim would be presumed valid. In addition, the court made clear that the lawful travel exception provided by Title III was an affirmative defense that would need to be established by the defendant, not negated by the plaintiff. Although it is still early in the litigation, the court’s decision may be promising to plaintiffs in stating the claims and may be encouraging to others to file causes of action.

With more questions than answers at this point regarding the scope of liability for entities conducting business in or with Cuba, the bar should watch carefully for the outcome of upcoming federal cases pending in the Southern District of Florida. Due to the broad definition of “trafficking” and treble damages, it is likely that most claimants will seek to hold liable entities that directly or indirectly profit from “trafficking.” The federal cases are still pending, but the upcoming decisions should provide useful insight into how US courts will respond to the novel Helms-Burton claims. In the meantime, entities doing business in Cuba should heed the litigation risk and consult counsel before embarking on a transaction that could trigger Title III.

Peter B. “Bo” Rutledge is dean of the University of Georgia School of Law, where he holds the Herman Talmadge Chair of Law. He is a former clerk to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

Katherine M. Larsen is a third-year law student at the University of Georgia School of Law.

Miles S. Porter is a second-year law student at the University of Georgia School of Law.