The last gasp of the Cuban Collapseniks

Once they recovered from the shock of U.S. President Barack Obama’s Dec. 17 announcement that he intended to normalize relations with Cuba, critics responded with a stale narrative: that the Cuban economy is teetering on the brink of collapse and that Obama threw the Castro dictatorship an economic “lifeline” that will keep the regime afloat, thereby snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

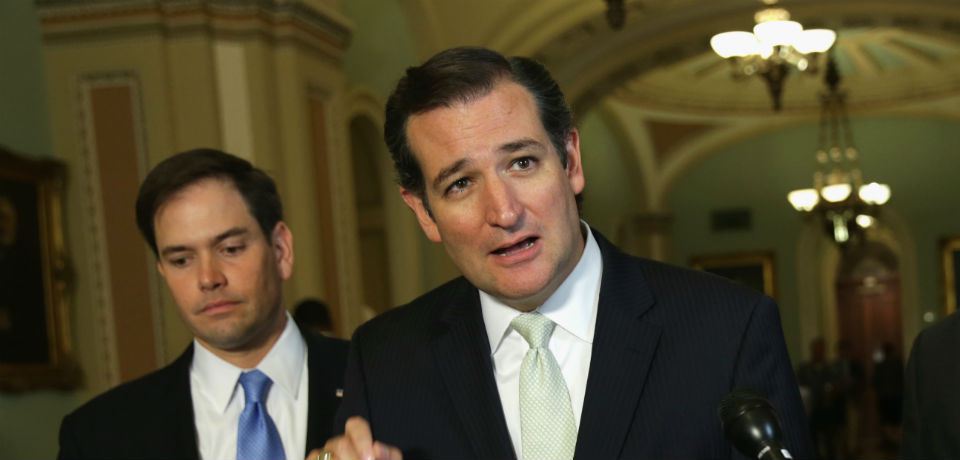

“It is a lifeline for the Castro regime that will allow them to become … a more permanent fixture,” said Sen. Marco Rubio, Obama’s most vociferous critic.

“Fidel and Raúl Castro have just received both international legitimacy and a badly-needed economic lifeline from President Obama,” echoed Sen. Ted Cruz.

Editorializing against the new policy, the Washington Post chimed in, “In recent months, the outlook for the Castro regime in Cuba was growing steadily darker…. [T]he Castros suddenly obtained a comprehensive bailout — from the Obama administration.”

In the initial round of House and Senate hearings on the new Cuba policy, opponents of Obama’s policy accused the president of making unilateral concessions that will prop up the Cuban economy without getting anything in return. “Havana is facing the threats of losing Venezuelan oil subsidies and mounting public pressure for basic reforms within the country, and this could have been used to leverage meaningful political concessions on human rights in Cuba,” claimed House Foreign Affairs Committee chairman Ed Royce (R-Calif.) in his opening statement. This critique plays into the Republican narrative that Obama is weak on foreign policy and dodges the inescapable fact that the old policy of extracting concessions from Havana by economic coercion was a spectacular failure.

The critics’ argument goes like this: Venezuela is in dire economic straits because of mismanagement and the falling price of oil, so it will have to drastically cut its oil subsidy to Cuba. Havana is so dependent on cheap Venezuelan oil that cuts would either lead to regime collapse or force Raúl Castro to give in to Washington’s demands for democratic concessions. But instead of stepping up the pressure on Castro, Obama foolishly gave the game away with a deal that provides Cuba with the economic breathing space to survive the impending “Venezuelan shock.”

This is nonsense for several reasons, but like all good polemics, it is built around kernels of truth. The Cuban economy is limping along, with an anemic 1.3 percent growth rate in 2014, and is more dependent on Venezuelan oil than Raúl Castro would like. Venezuela is, indeed, in the midst of an economic crisis that may well force it to reduce the Petrocaribe oil price subsidies it grants to neighboring countries, including Cuba.

But Cuba has a privileged relationship with Caracas and is less likely than most to suffer a significant cut in its oil supply. Cuba imports a little over half of its oil from Venezuela, paid for in kind by the work of some 40,000 Cuban medical professionals. Since the Cuban health care workers serve in the poorest neighborhoods — the core of President Nicolás Maduro’s base — it is unlikely that he would send the Cubans home so long as he can continue to pay for them with oil — especially as the value of that oil on the world market is declining. Last year, Venezuelan shipments of subsidized oil to other Petrocaribe participants fell by 19 percent, but Cuba received its full allocation.

In the worst-case scenario, what would be the economic impact if Cuba had to replace Venezuelan oil on the world market? Economist Pavel Vidal has made one of the few serious efforts at macroeconomic modeling to answer that question. If trade with Venezuela declined gradually, falling to near zero over five years, the Cuban economy would suffer a 4 percent loss of GDP. If trade suddenly fell to zero in just one year, Cuba would suffer a 7.7 percent loss of GDP — a severe recession, no doubt. But Vidal’s analysis was done a year ago, when the price of oil was $90 a barrel. Today, replacing Venezuelan oil would cost Cuba only half as much.

When aid from the Soviet Union disappeared in 1991, Cuba’s GDP dropped at least 35 percent. That depression, known as the Special Period, lasted well over a decade, but the Cuban regime did not collapse; it barely even tottered. To think that the loss of Venezuelan oil would destabilize the Cuban government is a fantasy.

Nor is there any chance that a “Venezuelan shock” would cause Raúl Castro to suddenly surrender to U.S. demands for political reform. In the 54 years since the breakdown of U.S.-Cuban relations, Cuba has never been willing to countenance such demands, which it regards as an infringement on its sovereignty — not even at the depths of the Special Period. For critics to insist on this impossible condition as the price for normalization is merely a disguise for their opposition to any policy change.

To claim that Obama bailed out Castro, critics have to posit that the president’s new policy provides an enormous economic windfall to Cuba. This, too, is a dubious proposition. The new travel regulations will make it easier for travel providers to organize trips, but tourism is still prohibited. Even if the number of non-Cuban American visitors doubled from about 100,000 last year to 200,000, that would only represent an increase of just 3 percent in Cuba’s tourist economy, which hosted 3 million visitors last year. It is too early to know how many new visitors will travel to Cuba now that it is more convenient, but visions of a million or more U.S. tourists flooding the island are overwrought.

Similarly, although Obama’s decision to license U.S. trade with the Cuban private sector is potentially important for the future, only about 9 percent of the labor force is privately employed outside agriculture, and another 12 percent works on private farms. Most private businesses are undercapitalized and not in a position to buy large quantities of inputs from U.S. exporters. They are more likely to continue receiving sub rosa investments and goods from relatives in the United States under the guise of remittances and gift packages — something they’ve been doing since 2009.

Finally, the regulatory changes regarding remittances do not affect Cuban-American family remittances, which have been unlimited since 2009 (and have more than doubled since then). The new regulations increase the amounts that can be sent by non-Cuban Americans, which is a very small proportion of the total flow — hardly enough to affect the macroeconomy.

Raúl Castro undoubtedly sees a long-term economic benefit in the normalization of U.S.-Cuban relations, but the real payoff will come only when the embargo is lifted, opening Cuba to unrestricted U.S. trade and investment. That is still far down the road.

Advocates of hostility have been predicting the Cuban regime’s imminent demise ever since 1959. Dwight D. Eisenhower expected Fidel to be gone “not later than the end of 1960.” After the collapse of European communism, the CIA predicted the fall of the Cuban government in a matter of months. The administration of George W. Bush believed that the regime could not survive the loss of Fidel Castro, its charismatic founder. For true believers in the old policy of hostility, no record of failure is enough to justify a new approach. The elusive moment of victory is always just around the corner.

The narrative of how a weak President Obama rescued communist Cuba from certain doom and missed the opportunity to demand democracy in return for normalization is just the latest version of this old antiquated story. It was wrong in 1959 and it is still wrong today.

(From: FP)