Large: Ai Weiwei takes over Alcatraz with Lego carpets and a hippie dragon

Welcome to prison, and a celebration of liberty. Ai Weiwei, the big man of Beijing, has spent years discovering pockets of freedom in the most straitened circumstances, resisting every effort by the Chinese government to shut him down.

This week he opens a major new exhibition in a place that makes that resistance literal: on Alcatraz, the island penitentiary in the San Francisco bay. The United States has the highest incarceration rate on the planet. But this prison is decommissioned, and Ai is using it to extraordinary effect.

Ai has not stopped exhibiting since his arrest in 2011, and if anything his art has grown more antagonistic and more vital since being carted away by the Beijing police. (He evoked his detention at last year’s Venice Biennale, via uncanny scaled-down dioramas of his prison cell.) But Alcatraz is a different beast from anything that’s come before. It’s not a museum but a major tourist attraction, with an audience that may or may not be disposed to contemporary art, and Ai’s art has been totally integrated into the historical site. It has never hosted anything like this before.

The logistical questions were cumbersome enough. Alcatraz is not equipped for art installations, let along the massive ones Ai favors. The artist is not allowed to leave Beijing, and had to entrust the installation to collaborators. But then there are the political hurdles that had to be negotiated. This is a show that praises several of the Obama administration’s chief antagonists, notably Edward Snowden, alongside political prisoners in China and the Middle East. It does so, by the way, on a US national park site, with visitors far more numerous than even the most famous artist since Andy Warhol will be used to.

In the fearsome main cellblock of Alcatraz – with tourists milling about everywhere – Ai has outfitted a dozen ground-level cells with gleaming steel stools, each one weighing 150lbs, pristine against the chipped paint and sallow lighting of the penitentiary. Through grates in the walls you hear something: music, or in a few cases poetry or speeches, by prisoners of conscience the world over. In one cell the Tibetan singer Lolo, now serving a six-year sentence for what the Chinese government calls “splittism,” warbles a plea for Tibetan independence over pizzicato strings. In another cell you hear Martin Luther King’s incendiary 1967 speech opposing the war in Vietnam and calling for “world revolution,” while Pussy Riot and the Plastic People of the Universe play nearby.

The last cell, so narrow you can’t fully extend your arms, is blastingSorrow, Tears and Blood, Fela Kuti’s anthemic denunciation of South African apartheid and Nigerian police brutality. Against the cell’s peeling walls and grimy sink and toilet, Ai’s stool and Fela’s saxophone hold out the promise of bold but joyous antagonism.

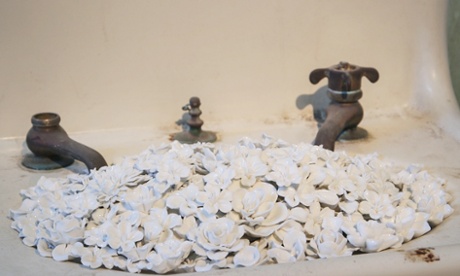

Upstairs is the medical wing. In the sinks, toilets, and bathtubs are white flowers made of porcelain, a material Ai has returned to again and again in his career. They’re get-well-soon offerings, or funerary bouquets. They’re also a biting evocation of Mao’s “let a hundred flowers bloom” crackdown of the 1950s, in which surface offerings of free expression disguised brutal government retribution.

Alcatraz had a notoriously high suicide rate, and up in the hospital wing are two grim isolation cells for mental patients, with tiled walls and a food slot in the door. Normally not open to the public, the cells host another sound piece: a chant from the Hopi nation, one of the Native American tribes whose members were imprisoned on Alcatraz in the late 19th century. (The US government, keen to extinguish Native American culture, attempted to force Hopi children into substandard state-run schools; parents who resisted were jailed.)

Interwoven with the drums and singing of the Hopi performance are incongruous droning horns, performed by exiled Tibetan monks in India. Now that America and China are so intertwined as to be essentially one country – a fact you can’t forget here in San Francisco, where everyone is coding apps for phones made in Shenzhen – Ai’s mashup of the two nations’ oppressed minorities reverberates as a call for reckoning beyond national borders.

Away from the prison, in a decommissioned industrial building usually off limits to visitors, are Ai’s three largest works. On the lowest level, viewable from a narrow corridor meant for gun-toting overseers, is Refraction, a swooping five-ton sculpture in the vague shape of a bird’s wing. The corroded metal armature, straight from Beijing but uncannily rhyming with Alcatraz’s rusting infrastructure, supports dozens of rippling, reflective metal sheets. Look on their backs, though, and the Chinese branding reveals that they’re reconstituted solar panels, utilized for cooking in off-the-grid parts of Tibet. Interrupting the avian wall of metal are reclaimed Tibetan cooking vessels: a kettle, a wok, a cheap aluminum steamer.

Upstairs is an undulating Chinese paper dragon, suspended from the ceiling. The dragon bears his teeth, but he’s harmless: his eyes are in the shape of the logo of Twitter, native to San Francisco and banned in the People’s Republic. The rainbow-colored segments of his body that wind through the factory bear quotations from Nelson Mandela (“Our march of freedom is irreversible”) and Edward Snowden (“Privacy is a function of liberty”: a bit pat for my taste, that line). Its rainbow color palette, and its naked invocation of activist heroes, make the dragon a much more hippie-friendly work than usual from Ai, whose sculptures are usually politically blunt yet formally impassive. But crusty radicals visiting from Berkeley will love it.

In the final room is Trace, the show’s most ambitious work, consisting of six large carpets of Lego blocks that depict, in pixelated but legible form, more than 175 prisoners of conscience, past and present. The first panel includes Mandela, Snowden, and Chelsea Manning, but also lesser known political prisoners such as Agnès Uwimana Nkusi, a jailed Rwandan journalist (just released after four years). One of the largest images, composed of blue and white Legos, is of a smiling Liu Xiaobo, the imprisoned writer and Nobel laureate. He is not the only jailed or exiled opponent of the CCP. Ai has also depicted the human rights attorney Gao Zhisheng, the blind civil rights activist Chen Guangcheng, the democracy advocate Li Tie, and many more.

The scale of the Lego carpets, and the painstaking labor from dozens of assistants required to execute it, recall his masterpiece Sunflower Seeds, an overwhelming collection of hand-painted porcelain ovals installed in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern. (As with the cordoned-off Sunflower Seeds, Ai had to place limits on this work too; he wanted visitors to walk across the Legos, but Alcatraz’s administrators said no chance.)

But the franker hero worship of Trace – verging on agitprop, really – is light-years away from Sunflower Seeds’ sensitive metaphoric evocation of 1.3 billion Chinese. It’s as if, in the years since his detention, Ai has given up on metaphor. He sees art less as a means of self-expression and more as a global lingua franca. Contemporary art, in his view, requires and perhaps even creates an audience committed to liberty. Presenting his art in a prison amplifies that goal twice over.

Call it transparent, call it unsubtle. Ai Weiwei’s years of small gestures, hisdropped Han Dynasty urn or his coathanger portrait of Marcel Duchamp, are long behind him. But I am tired beyond belief of the peevish and western-centric commonplace that Ai is, somehow, both a heroic activist and a mediocre artist. He can’t be cleaved apart like that, not anymore. Since 2008, and the massive Sichuan earthquake that radicalized his artistic practice, his art and activism have become indissolubly joined into a single enterprise, ambitious, open-hearted, and indispensable in an art world more than happy to look the other way at abuses in China and everywhere else. The bravery and commitment he exhibits at Alcatraz, a place he may never be allowed to visit, should be more than enough to convince any remaining doubters that he is not joking around.

In the Alcatraz commissary, on two simple teak racks, Ai has provided pre-addressed postcards for the 5,000 tourists a day who traipse through the prison, inviting them to write to the crusaders languishing in jails like this one, or the one he found himself in just three years ago.

Not all of Ai’s heroes are reachable, of course; Liu Xiaobo, Nobel Prize be damned, is still incommunicado in a prison in Liaoning. You can, however, send a message to Li Tie, in a prison in Hubei. Or to Mohammad al-Qahtani, an economics professor, jailed in Saudi Arabia for human rights activism. You can write to Cuba, or Bahrain, or to a dozen other places where free expression will get you jailed. Ai Weiwei you can reach on Twitter.

*Take a tour of the large scale installations using Lego, traditional kites and porcelain flowers at the famous San Francisco penitentiary: here.

(From the: The Guardian)