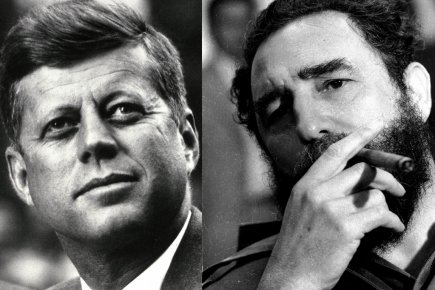

Kennedy’s last act: Reaching out to Cuba

By Peter Kornbluh

The 50th anniversary of the violent death of U.S. president John F. Kennedy has yielded a long kept secret: in the aftermath of the assassination in Dallas, Fidel Castro sent a back-channel message to Washington that he wanted to meet with the official commission investigating Kennedy’s murder, to dispel the swirling allegations that Cuba was responsible. The Commission, headed by Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Earl Warren sent a young African-American staff lawyer, William Coleman, on a clandestine mission to rendezvous with the Cuban leader on a boat in the Caribbean.

They talked for three hours, Coleman recalled in the first interview he ever gave on the Top Secret meeting to investigative reporter Philip Shenon. Despite pressing the Cuban leader on Cuba’s ties to Lee Harvey Oswald and his mysterious visit to the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City before the assassination, Coleman reported back to Warren that he “hadn’t found out anything to cause me to think there is proof [Castro] did it.” Indeed, despite Playa Giron, the missile crisis, assassination plots and the trade embargo, Castro insisted that “he admired President Kennedy.”

Secrets and Conspiracy Theories

In the United States, the anniversary of the young president’s death has generated massive media coverage—special television documentaries; a slew of new books and articles, a new Hollywood movie. Inevitably, the many conspiracy theories as to who killed Kennedy and why are once again being debated. The Warren Commission concluded that Oswald, a deranged loner and self-declared Marxist, acted alone when he shot the president. But U.S. government secrecy, particularly the fact that the CIA withheld information on its Top Secret efforts to kill Castro, and on its surveillance of Oswald when he visited Mexico City—protecting its extensive intelligence gathering operations in Mexico—fueled suspicions of a cover-up. Nor did the White House share the extraordinary details of significant developments in Kennedy’s attitude toward Cuba—a country central to any historical discussion of the president’s shocking murder in Dallas fifty years ago.

Almost immediately following the assassination on November 22, 1963, enemies of the Cuban revolution began planting accusations that the pro-Castro Oswald had conspired with Cuba to kill the president. In New Orleans, where Oswald had created a one-man “Fair Play for Cuba” committee, a CIA-backed exile group, the Revolutionary Student Directorate (DRE), published its newsletter on November 23 with a picture of Castro next to a picture of Oswald. Six days after the assassination, CIA director John McCone reported to the new president, Lyndon Johnson, that a Nicaraguan intelligence agent in Mexico City named Gilberto Alvarado had “advised our [Mexico] station in great detail on his alleged knowledge that he actually saw Oswald given $6,500 in the Cuban Embassy in Mexico City on September 18th.” Alvarado claimed the money was payment to kill the president.

The CIA was immediately suspicious about the credibility of this intelligence because the FBI had concrete proof that Oswald was in New Orleans on September 18th; immigration documents showed he did not travel to Mexico City until September 26. Alvarado was held in a CIA safe house and then turned over to Mexican authorities for further questioning. He failed a CIA-administered polygraph test, and retracted his statement. According to a Top Secret CIA report titled “Assassination of President Kennedy,” Alvarado “admitted to Mexican authorities his story was a fabrication designed to provoke U.S. into kicking Castro out of Cuba.”

Castro himself saw a very different conspiracy at work. On November 23rd he broadcast a statement on Cuban radio in which he labeled the Kennedy assassination “a Machiavellian plot against our country” to justify “immediately an aggressive policy against Cuba…built on the still warm blood and unburied body of their tragically assassinated President.” Oswald, he stated, may have been “an instrument of the most reactionary sectors that have been planning a sinister plot, who may have planned the assassination of Kennedy because of disagreement with his international policy.”

At the time of this dramatic statement, Castro knew something about Kennedy’s international policy that the rest of the world did not: at the time of his assassination Kennedy was actively exploring a rapprochement with Cuba, and working secretly with Castro to set up secret negotiations to improve relations. In November 1963, Cuba had no reason to assassinate Kennedy because they were engaged in back channel diplomacy that could possibly lead to normalized relations. Indeed, at the very moment Kennedy was killed, Castro was meeting with an emissary he had sent to Havana on a “mission of peace.”

Secret U.S.-Cuban Talks

The talks between Cuba and the U.S. began, ironically, around Washington’s bald act of aggression—the paramilitary invasion at Playa Giron. In the aftermath of Cuba’s victory over the CIA-backed brigade, the President and his brother, Robert Kennedy sent a lawyer named James Donovan to negotiate the release of over 1,000 captured brigade members. During the course of several negotiating sessions in the fall of 1962, Donovan brokered a deal to supply Cuba with $62 million in food and medicine in return for the release of the prisoners. He not only won their freedom but the trust of Fidel Castro as well.

In the spring of 1963, Donovan returned to Havana several times to negotiate with Castro the release of two dozen Americans—three of them were CIA operatives–imprisoned in Cuban jails on charges of spying and sabotage. During the course of their meetings, Castro for the first time raised the issue of restoring relations. Given the acrimony and hostility of the recent past, “how would the U.S. and Cuba go about it,” he asked Donovan.

“Do you know how porcupines make love?” Donovan replied. “Very carefully. And that is how you and the U.S. will go about this issue.”

When Donovan’s report on Castro’s interest in talks to normalize relations reached the desk of President Kennedy, the White House began considering the possibility of a “sweet approach” to Castro. Top aides argued that the U.S. should demand that Castro jettison his relations with the Soviets as a pre-condition to any talks. But the President overruled them; he instructed his top aides to “start thinking along more flexible lines” in negotiating with Castro, and made it clear, according to declassified White House documents, that he was “very interested” in pursuing this option.

On his last trip to Cuba in April 1963, Donovan introduced Castro to a correspondent for ABC News named Lisa Howard who had traveled to Havana to do a televised special on the Cuban revolution. She replaced Donovan as the central interlocutor in a protracted secret effort to set up the first serious face-to-face talks on better relations. When she returned from Cuba, the CIA met her in Miami and debriefed her on Castro’s clear interest in improved relations. In a top secret memorandum that arrived on the desk of the president, CIA deputy director Richard Helms reported that “Howard definitely wants to impress the U.S. Government with two facts: Castro is ready to discuss rapprochement and herself is ready to discuss it with him if asked to do so by the U.S. Government.”

Predictably, the CIA adamantly opposed any dialogue with Cuba. The agency was institutionally invested in its on-going efforts to covertly roll back the revolution. In a secret memo rushed to the White House on May 1, 1963, CIA Director John McCone requested that “no active steps be taken on the rapprochement matter at this time” and urged only the “most limited Washington discussions” on accommodation with Castro.

But in the fall of 1963, Washington and Havana did take active steps toward actual negotiations. In September Howard used a cocktail party at her E. 74th Street Manhattan townhouse as cover for the first meeting between a Cuban official, UN Ambassador Carlos Lechuga, and a U.S. official, deputy UN Ambassador William Attwood. Attwood told Lechuga that there was interest at the White House in secret talks, if there was something to talk about. He also noted that “the CIA runs Cuba policy.” Following that meeting, Castro and Kennedy used Howard as an intermediary to began passing messages about arranging an actual negotiation session between the two nations.

On November 5, Kennedy’s secret taping system in the Oval Office recorded in a conversation with his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, on whether to send William Attwood, who was serving as a deputy to U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson at the United Nations, to Havana to meet secretly with Castro. Attwood, Bundy told the President, “now has an invitation to go down and talk to Fidel about terms and conditions in which he would be interested in a change of relations with the U.S.” The president is heard agreeing to the idea but asking if “we can get Attwood off the payroll before he goes” so as to “sanitize” him as a private citizen in case word of the secret meeting leaked.

On November 14, Howard arranged for Attwood to come to her home and talk via telephone to Castro’s top aide, Rene Vallejo, about obtaining the Cuban agenda for a secret meeting between in Havana with the Cuban comandante. Vallejo agreed to transmit a proposed agenda to Cuba’s UN ambassador, Lechuga, to give to the Americans. When Attwood passed this information onto Bundy at the White House, he was told that when the agenda was received, “the president wanted to see me at the White House and decide what to say and whether to go [to Cuba] or what we should do next.”

“That was the 19th of November,” Attwood recalled. “Three days before the assassination.”

Kennedy’s Final Act

But Kennedy also sent another message of potential reconciliation to Castro. His emissary, a French journalist named Jean Daniel, had met with Kennedy in Washington to discuss Cuba. Kennedy gave him a message for Fidel Castro: Better relations were possible, and the two countries should work toward an end to hostilities. On November 22, Daniel passed that message to Castro, and the two were discussing it optimistically over lunch when Castro received a phone call reporting that Kennedy had been shot. “This is terrible,” Castro told Daniel, realizing that his mission had been aborted by an assassins’ bullet. “There goes your mission of peace.”

Castro then accurately predicted: “They are going to say we did it.”

Amidst the ongoing controversies over conspiracy theories, what is lost in the historical discussion of the assassination is that John F. Kennedy’s very last act as president was to reach out to Castro and offer the possibility of a different bilateral relationship between Havana and Washington. Fifty years later, the potential Kennedy envisioned for co-existence between the Cuban revolution and the U.S. has yet to be realized. As part of commemorating his legacy, his vision for a détente in the Caribbean must be remembered, reconsidered, and revisited.

Peter Kornbluh directs the Cuba Documentation Project at the National Security Archive in Washington D.C., and is co-author, with William LeoGrande of the forthcoming book, Talking With Cuba: The Hidden History of Diplomacy between the United States and Cuba.

(From the National Security Archive. Originally published in Spanish in La Jornada.)