It is important not to confuse patriotism with nationalism

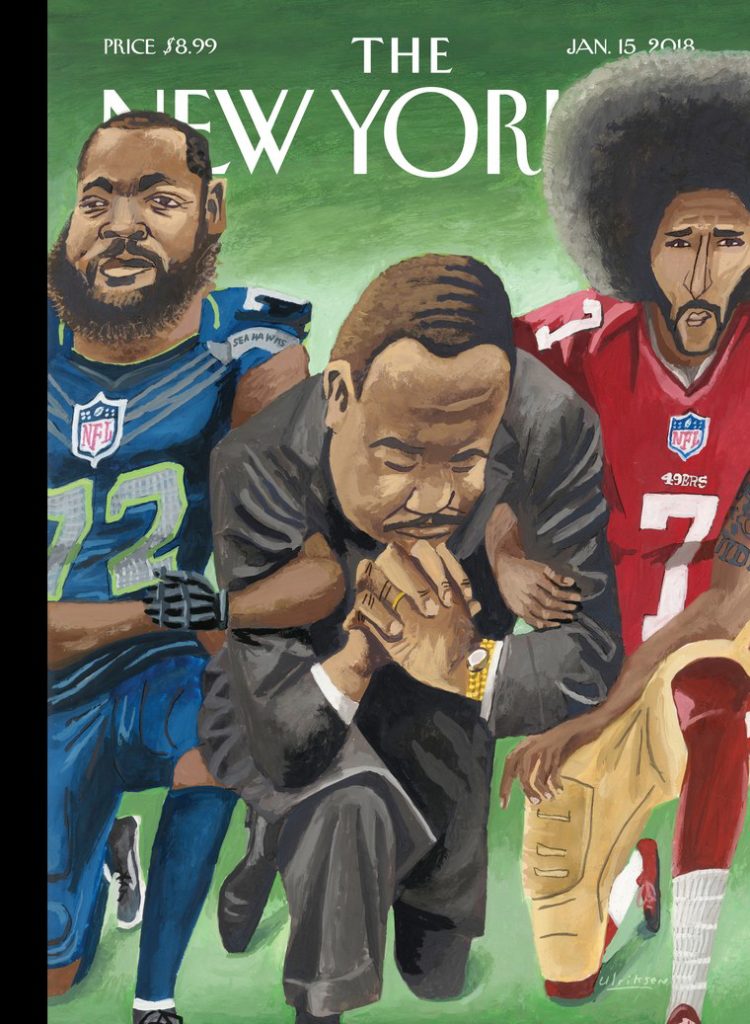

When I saw the cover of this week’s The New Yorker I took a deep breath. It shows Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. kneeling, arms locked, alongside two NFL players, Colin Kaepernick and Michael Bennett. Provocative? Yes. In keeping with the Dr. King I met and covered as a reporter? There is little doubt in my mind.

In WHAT UNITES US, I wrote, “We have a long history in the United States of marginalized voices eventually convincing majorities through the strength of their ideas. Our democratic machinery provides fertile soil where seeds of change can grow. Few knew that better than King.”

I think it is highly likely that Dr. King would have seen these NFL protests as a patriotic act. He understood that principled dissent was part of #WhatUnitesUs. As I wrote in another section of the book:

“In his 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech during the March on Washington, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. offered one of the most eloquent personal visions of American patriotism ever delivered. Using the logic of economics to make a moral point, King called for an incredible debt to be paid. “In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check,” he said. “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.” The reckoning, King said, was long overdue: “We refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

In my mind, King wasn’t calling for a revolution, even though that is how many at the time perceived it. He wasn’t even arguing that there was something inherently rotten with the protections and provisions under which the United States was founded. Rather, he believed, and justly so, that the translation of those ideals into practice had been lacking. If our constitutional protections had been dispensed more equally and fairly, he asserted, then the dreams of which he spoke would be a lot closer to reality. King was not restrained in his criticism of the status quo, but he spoke freely and with the moral backing of our founding documents. In my years covering the civil rights movement, I was always struck by the fierce determination of these men and women to fight for their place in the future of a country that had mistreated them. They were infused with an unbreakable optimism that they would prevail. This spirit has been echoed time and again by those who have demanded their full constitutional rights as American citizens.

I have long been suspicious of those who would vociferously and publicly bestow the title of “patriot” upon themselves with an air of superiority. And I have generally taken a skeptical view of those who are quick to pass judgment on the depths of patriotism in others. George Washington, in his famous Farewell Address, warned future generations “to guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism.” I like to think of this as an admonition, not only to be wary of the patriotic posturing of others, but also to be alert to the stirrings of pretended patriotism within oneself.

It is important not to confuse “patriotism” with “nationalism.” As I define it, nationalism is a monologue in which you place your country in a position of moral and cultural supremacy over others. Patriotism, while deeply personal, is a dialogue with your fellow citizens, and a larger world, about not only what you love about your country but also how it can be improved. Unchecked nationalism leads to conflict and war. Unbridled patriotism can lead to the betterment of society. Patriotism is rooted in humility. Nationalism is rooted in arrogance.”

(From the Dan Rather Facebook page.)