How Mies van der Rohe’s Design for a Bacardi HQ in Cuba Became Berlin’s Iconic Neue Nationalgalerie

The Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, long considered to be Ludwig Mies van der Rohe‘s final masterpiece, opened in 1968 on a barren stretch of land not far from the border checkpoints of the Berlin Wall, which was just seven years old at that point. It was not the first time the monumental building with its elevated glass pavilion had been uncomfortably close to the vicissitudes of history. Van der Rohe originally designed a version of the building for the Bacardi rum company’s headquarters in Santiago de Cuba. However that building was never completed, due to the Cuban revolution, which saw the Bacardi family exiled from Cuba and their assets seized in 1960.

The story of how a glassy modernist building designed for a tropical island ended up in cold, rainy Berlin eight years later is an intriguing one. Naturally, Mies made some changes. “In Cuba he planned in stone for the climate,” says Neue Nationalgalerie director Joachim Jäger. “In Berlin he thought it would be interesting to work in steel.”

Van der Rohe’s association with Bacardi dates back to 1929, when the architect and the liquor company both won prizes at the Barcelona International Exposition: Mies for his now-iconic Barcelona pavilion, and Bacardi for their smooth white rum. In 1957, company president Jose “Pepín” Bosch hired Mies to design an “office without walls” for the headquarters in Santiago de Cuba, as well as for a plant in Mexico City.

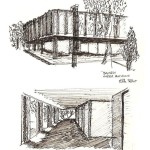

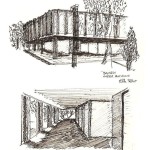

Bosch told the architect that he wanted an office “where there were no partitions, where everybody, both officers and employees, could see each other.” Mies immediately grabbed a cocktail napkin and began to make sketches on it. By January 1959, the design, which saw a square roof supported by two columns on each side, was ready; van der Rohe flew to Havana and presented it to Bacardi at the Hilton Hotel.

That very same month, however, the revolutionary Fidel Castro and his followers succeeded in ousting Cuba’s dictator Fulgencio Batista from the presidential office, replacing his corrupt government with a socialist one. Castro’s new government quickly nationalized many industries and seized the property and assets of businesses and wealthy landowners. “The Bacardi family lost everything in Cuba and had to restart the enterprise in a new base, a new country,” says Dr. Jäger, of the Neue Nationalgalerie.

And so it was that the striking building meant to be an innovative open headquarters for Bacardi ended up filed away in van der Rohe’s architecture office in Chicago. But in the early 1960s, Mies received two German museum commissions, and tried to reconfigure the abandoned Bacardi design for both of them. One, meant to house an industrialist’s collection of 19th-century art in the mid-sized Bavarian town of Schweinfurt, was never built. The other one became the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, which showcases the German state’s collection of modern art alongside cutting-edge temporary exhibitions. It opened in September 1968, less than a year before van der Rohe passed away, at the age of 83.

“It’s the last building he really planned from A to Z,” says Jäger. The primary exhibit hall is a glass pavilion with high ceilings and a cantilevered steel roof. Save for eight columns supporting the flat roof, the nearly-29,000-square-foot hall is a completely open space. Because of the vast proportions of the room, which is 164 feet wide, smaller artworks can get swallowed; large and dramatic installations work best. The museum is currently undergoing a full restoration by the British architect David Chipperfield, who mounted an exhibition of 144 tree trunks in the pavilion last fall.

“It’s such an intense space,” explains Jäger. “You cannot bring in papers or paintings because there is so much light. You have to specially design exhibitions around it.”

“It’s such an intense space,” explains Jäger. “You cannot bring in papers or paintings because there is so much light. You have to specially design exhibitions around it.”

The museum’s permanent collection is spread over 110,000 square feet in a partially subterranean level under the striking glass hall. It’s an atypical design for a gallery space, to be sure, but the building’s challenges also make it extremely interesting to curate displays for. No exhibition ever looks the same, since artists are compelled to enter into a dialogue with the pavilion. The German sculptor Imi Knoebel painted the glass panes of the hall in various shades of white, while the American photographer Taryn Simon chose to display her work in huge rectangular boxes that matched the anthracite color of the ceiling.

If the building had been made for Bacardi, offices would have been located downstairs, and “the glass house might have been a big lobby for parties with whiskey and cigars.”

Luckily for Berlin, it became an exceptional museum instead. “Having visited Toronto and Chicago, I think of this as the conclusion of Mies’ life’s work,” says Jäger. “It’s an extreme and very successful solution.”

(From: Cuebed)