Higher wages in joint ventures: Not enough incentive?

Opinion

HAVANA — Cubans who work in joint-venture enterprises know the salary increase that was promised after the approval of the new Law on Foreign Investment. But they had hoped for a much larger increase.

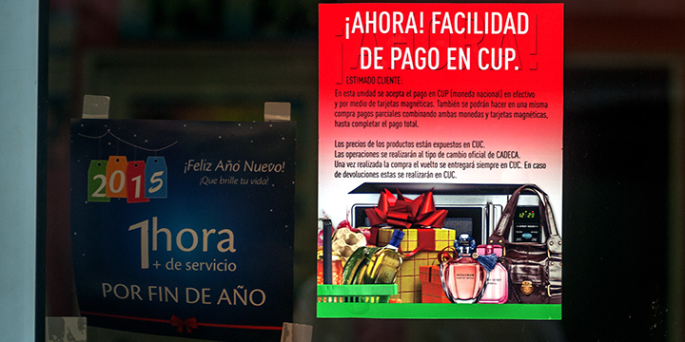

The government’s decision defines a “coefficient” of 2 to multiply the salary paid by the foreign investor to a Cuban government agency for each worker. And there’s a need to multiply because the foreign employer pays his workforce in convertible Cuban pesos (CUC) but the worker receives his salary in plain Cuban pesos (CUP).

Thus, for instance, a chemical engineer working in a rum-processing plant set up as a joint venture may have been collecting 510 pesos (CUP) a month. Under the new resolution, he starts collecting 1020 CUP until a new salary is negotiated independently by all the entities, in early 2015.

The first change made by this measure is the acknowledgment of a new form of payment, because the stipends of the workers were centrally established, whereas now they can be negotiated according to each modality of investment, taking into account the salary that other workers in our geographical region earn.

There is a minimal condition: in no case may a worker earn less than what he earns now, and in no case may he be paid less than the median wage in the country — 471 CUP.

But the affair gets complicated, because the 40,000 workers involved must turn to the hard-currency market to buy staples such as detergent or cooking oil, and for that they must use an exchange rate of 1 CUC=24 CUP.

For that reason, many workers are amazed that the exchange rate of 1 CUC=2 CUP is applied to them. That means that, in the case of the chemical engineer, even though the foreign employer pays the government 510 CUC (convertible pesos) a month for his services, he will receive only 42.50 CUC from the government.

Logical? Fair?

Both adjectives are used, explicitly and implicitly, by workers reacting to the new measure.

A broad debate has been generated in the digital forum of the newspaper Granma, where several readers recall that a previous ruling had set a “coefficient” of 10 CUP=1 CUC for the wages for workers in the Special Development Zone at Mariel (SDZM).

Now, the substantial difference between 10 and 2 is unfair to readers like “Lazarus,” who opines: “It’s as if there were first- and second-class joint ventures, and first- and second-class workers.”

The Cuban authorities seem to have overcome the attitude of “egalitarianism above all,” as we see from the comments from the functionaries who announced the measure.

“To us, the SDZM is a fundamental effort that the country is making to attract foreign investment and that’s why we want the labor force in the Zone to have a coefficient that generates a higher wage,” says Deborah Rivas, director of Foreign Investment for the Ministry of Foreign Investment.

What cannot be doubted in both cases (and others, such as the one involving health-care workers) is that the government is enforcing its announced policy to reward the sectors that bring hard currency to the country.

But, beyond the willingness to stimulate, what really seems to be behind the notable difference between the “coefficients” is the lack of money in the government’s coffers, made worse by the continued existence of a dual currency — unlikely to disappear in early 2015, as some thought.

The problem is that, for the accounting purposes of business companies in Cuba, 1 CUC is equal to 1 CUP and therefore, even though the foreign businessman is charged in hard currency, the Cuban government records all revenue as “pesos” — no surname.

So, the government must create budget funds so its hiring agencies may have enough resources to double the amount of payments.

“The country is operating with monetary and exchange duality and we can’t interpolate the rate of exchange in business relations to relations with the population,” says Vladimir Regueiro, director of revenues at the Ministry of Finance and Prices. “We cannot apply coefficients for which we don’t have backing with our budget resources,” he said.

Insufficient salary

Unaware of such complexity, several workers directly involved with the new measure display little enthusiasm. To them, the most important thing is to continue to receive the “hidden” payments they get from their foreign contractors.

In almost all companies operating with foreign capital, the manager pays the workers sums equivalent to the difference between what his parent establishment considers a real salary and what the Cuban government charges for the workers.

That’s Marcos’ concern,* expressed to Progreso Weekly via an e-mail: “If that increase goes to my company’s account, will they reduce what they give me under the table?”

“Any increase is welcome but it’s insufficient,” says Dulce.* “I multiply by 2 and will continue to worry that all the prices are high, because they don’t divide them by 2. At home, we make do with what I get under the table, and with that money I pay what goes on the table.”

The belated nature of this decision (by law, it should have been approved last October, that’s why it’s being applied retroactively) and its temporary nature awaiting monetary unification guarantee that the problem of salaries in the vital sector of foreign investment is not a done deal at all.

To speak only of the benefit created by the rise in wages is seeing a glass half full. To notice that that increase remains below people’s needs and that the worker feels fleeced by the currency conversion reveals the portion of the glass that’s still not filled.

* Names changed at the request of the sources.