Fifty years after his death, Malcolm X speaks to the current moment

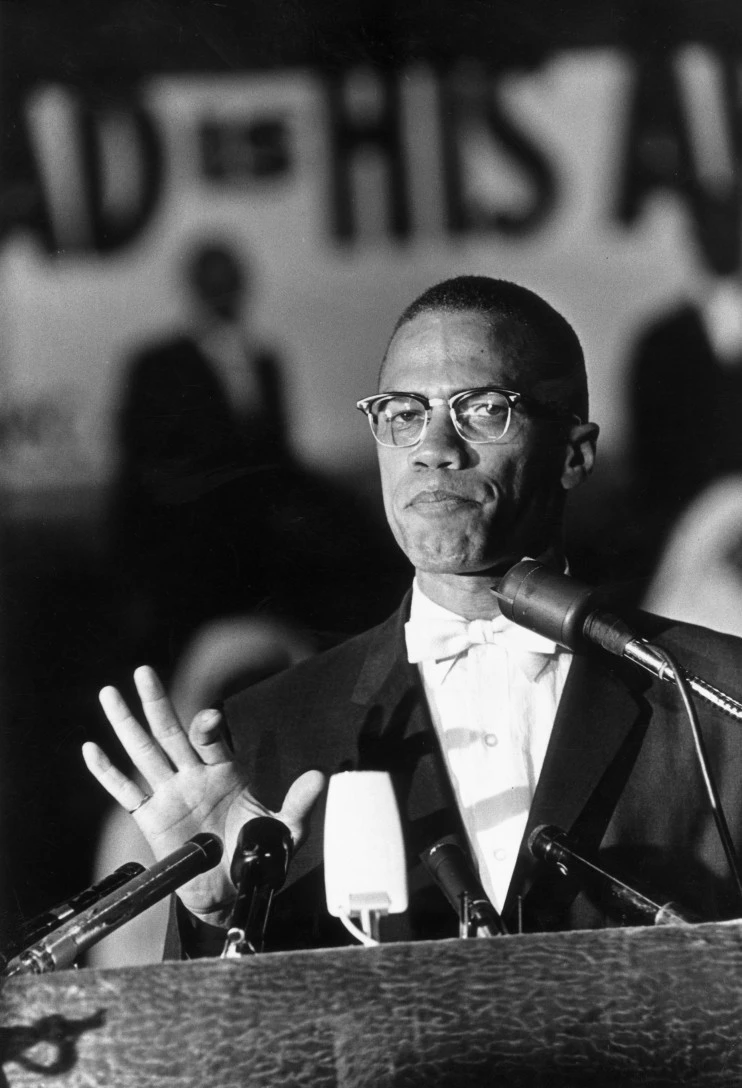

After a life filled with transformation, Malcolm X found himself in February 1965 in the throes of yet another.

He had been a fringe figure, known mostly to a small circle of black Muslims and big-city sophisticates, but now he was branching out — seeking allies at home and abroad to help him become a part of the Southern civil rights movement. He had plans to take the cause to the United Nations, charging the U.S. government with failure to protect its black citizens from racist white terrorism.

He was fashioning himself as an internationalist. A political player.

It was a transformation thwarted. History ended up casting Malcolm X as radical foil to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the nonviolent martyr. He was boiled down to his aphorisms: “By any means necessary.” “The ballot or the bullet.”

But 50 years after he was gunned down by an assassin in Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom, Malcolm X is getting another look. His issues — particularly those that occupied the last year of his life — and his tactics speak to the current conversation.

Police brutality? Malcolm would have been on point amid the protests in Ferguson, Mo., and Staten Island. “Whenever something happens, 20 police cars swarm on one neighborhood,” Malcolm told an interviewerduring his crusade against anti-crime bills. “This force . . . creates a spirit of resentment in every Negro. They think they are living in a police state and they become hostile toward the policeman.”

Voting rights? Once again in the spotlight, as activists challenge photo ID laws that they say hinder minority voters, and definitely a preoccupation for Malcolm. “When white people are evenly divided, and black people have a bloc of votes of their own, it is left up to them to determine who’s going to sit in the White House and who’s going to be in the doghouse,” he said in 1964.

So now scholars are holding forums on Malcolm’s legacy. His associates are drawing attention to the work he left unfinished. The Oscar-nominated film “Selma” features a cameo from Malcolm, dramatizing his efforts to reach out.

“He was on a committed campaign to internationalize the movement,” recalled Peter Bailey, who worked for the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), the political group that Malcolm founded less than a year before his death. Malcolm changed the conversation about the civil rights movement — and the way activists think of themselves — in ways that resonate today

“We called ourselves a human rights organization, not a civil rights organization,” Bailey added, “because human rights is an international term.”

Differences aside

Today’s civil rights movement has struggled with public rifts — younger protesters chafing against older activists over tactics. You can imagine Malcolm shaking his head and sighing.

Once the rebel, toward the end of his life he was seeking allies.

He had differences with King and other black leaders, but he wanted those differences to remain “in the closet,” Malcolm said in 1964. “When we come out in front, let us not have anything to argue about until we get finished arguing with the man.”

It was a dramatic shift. Malcolm had more than once implied that nonviolence was cowardly. He suggested that the peaceful Southern protesters should meet the violence of white lawmen with self-defense. But he respected the grass-roots sentiment there — and over time, his respect for King increased.

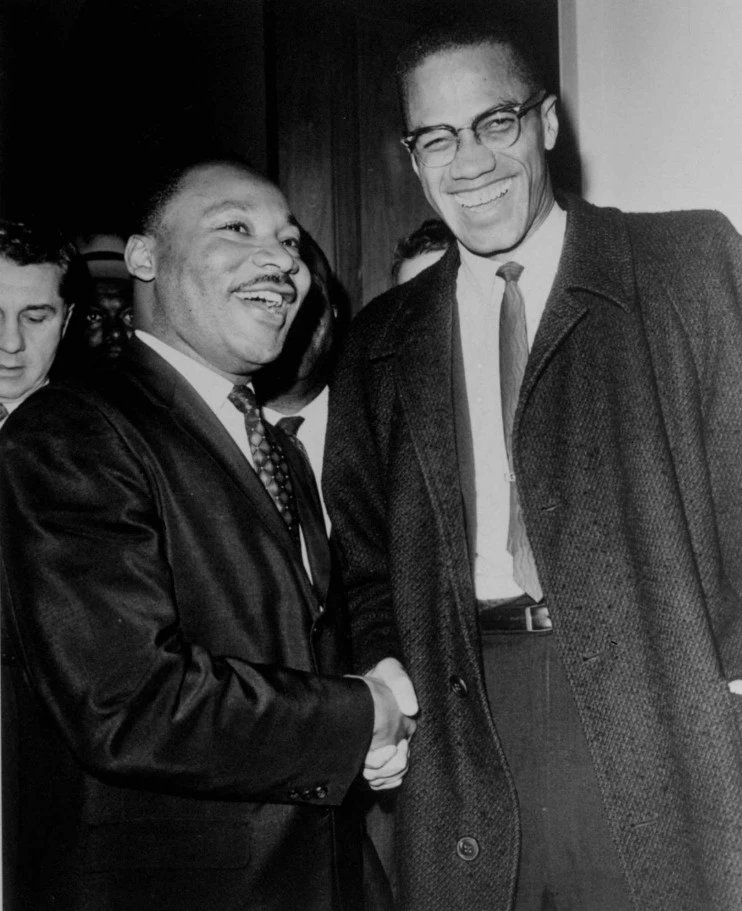

They’ve been compared so often, but the men only met once, a grip-and-grin for cameras as they passed in a Capitol Hill hallway in March 1964 after observing a filibuster over the proposed Civil Rights Act.

“Malcolm was pushed out awkwardly by an associate from behind a pillar,” said Garrett Felber, a researcher who worked with the scholar Manning Marable on his Pulitzer Prize-winning Malcolm X biography. “Standing in front of King, whom he had described as an ‘Uncle Tom,’ Malcolm shook hands with King before the press.”

In later years, their commonalities were clear.

Malcolm “wanted to be an inspirational force offering a different perspective than King,” said Clayborne Carson, a Stanford University historian who was selected by Coretta Scott King to edit her husband’s papers. “Both of them were internationalists. Both agreed that the African American struggle had to join ties with the struggle against colonialism and that they both saw the civil rights struggle as the struggle for human rights.”

Malcolm saw reason for them to work together. He wrote letters to King. He began to invite members of the Student-Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to Harlem to speak to his followers. Fannie Lou Hamer, the Mississippi voting rights activist, came, too.

Three weeks before he was killed, students at the Tuskegee Institute invited him to speak there, and he went to Selma, Ala., a couple of days later.

“It was an overture,” said Peniel Joseph, professor of history at Tufts University and the author of “Waiting ’Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power.” “He gave a speech and he told the press that Dr. King is right. He was presenting himself as an alternative and trying to help the movement.”

Local authorities wouldn’t allow Malcolm to meet with King, who was in jail, but Malcolm did have a conversation that afternoon with Coretta Scott King.

She was nervous, not knowing what to expect.

“He leaned over and said to me, ‘Mrs. King, I want you to tell your husband that I had planned to visit him in jail here in Selma but I won’t be able to do it now. . . . I didn’t come to Selma to make his job more difficult, but I thought that if the white people understood what the alternative was that they would be more inclined to listen to your husband,’ ” she recalled in the “Eyes on the Prize” documentary series.

She thanked him, she said — and later wondered how much he could have achieved had he lived.

By late February 1965, Malcolm was back in Harlem. He was planning for the future and thought he could do that by building up his organization.

“He was an organizer,” Bailey said. “He believed in structure.”

Malcolm was under threat after leaving the Nation of Islam and being surveilled by law enforcement, but he was determined to keep working, his nephew Rodnell Collins said.

“He did not want his children to see their father not fighting for a cause,” said Collins, who was 20 when his uncle was killed. He believed in “dying with your boots on, fighting for a cause.”

In a meeting with followers, Malcolm put to a vote whether he should speak at an upcoming event, recalled Lez Edmond, a friend who urged him to stay in the background for a while.

“The other side prevailed,” said Edmond, an associate professor at St. John’s University. “He put his arm around me and said, ‘Brother, you seem to be very upset.’ I said, ‘I am.’ But I didn’t see any fear in his eyes.”

On Feb. 21, Bailey was among the four or five people backstage to talk with Malcolm before he took the stage of the Audubon Ballroom.

“He told us he was going down to Jackson, Mississippi, to speak,” Bailey recalled. “Then he was going to spend six months building up OAAU.”

As Malcolm took the stage, someone in the audience called out, “Get your hand out of my pocket!” Before Malcolm’s bodyguards could calm the crowd, a man charged forward and shot him in the chest with a sawed-off shotgun. Two other men ran to the stage firing handguns. He was pronounced dead at 3:30 p.m. at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital.

Alex Haley’s “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” published later in 1965, turned him into a martyr. It was an all-American narrative of transformation and redemption: a criminal turned devoutly religious man, who traded Nation of Islam’s “white devil” rhetoric for a spirit of brotherhood. It recast the radical as the kind of man who would be commemorated on a U.S. postage stamp in 1999.

“I don’t know if he’d appreciate that,’’ the activist and black studies scholar Richard Newman said at the time. “It’s ironic to see him honored by the government he despised.’’

A less gauzy picture came into focus four years ago when Marable’s unflinching biography of Malcolm was published, revealing exaggerations and narrative liberties in the Haley-penned biography. But the portrait remained of a strong and formidable leader, said Mark Anthony Neal, professor of African and African American Studies at Duke University. He’s one of the organizers of “The Legacy of Malcolm X: Afro-American Visionary, Muslim Activist” conference being held at Duke this weekend. There he wants to talk about the forgotten Malcolm.

“The thing we forget is that Malcolm X, when all was said and done, he really was an incredible political strategist — and really a visionary,” Neal said. “He was someone who was constantly revising his views of the world, the way he would present his public persona, his ideas about radicalism and movements — civil rights movements, black power movements.”

As for today’s young activists, Malcolm’s influence continues. Taurean K. Brown, a 27-year-old based in North Carolina who writes and speaks about social justice, has found direction in Malcolm’s life and political positions.

Brown fashions himself as a Malcolm-type revolutionary — pushing for radical change instead of King’s gradual reforms. And in the rumbling protests following the deaths of Eric Garner in New York, Michael Brown in Ferguson and 12-year-old Tamir Rice in Cleveland, he sees an awakening the black nationalist leader would have admired.

“Malcolm’s legacy is fully entrenched in the uprising that is going on today,” said Brown, who was headed to a social-justice conference this weekend at the University of Texas at Arlington. “There is a heavy appreciation for black consciousness and black pride. His influence will always be powerful for youth because he connected with black youth in the ’hood, the disadvantaged. He understood.”

Ellen McCarthy contributed to this report.

(From: The Washington Post)