The end of the Cuban rafters

Twenty years ago, a massive exodus of Cuban rafters – some 35 thousand left the country – marked the beginning of the end for this type of illegal emigration. Washington and Havana reached an agreement whereby all Cubans captured at sea would be returned to the island.

The United States also agreed to issue 20 thousand travel visas every year and set in motion its “dry foot – wet foot” policy, under which anyone captured in Strait of Florida waters would be sent back to Cuba. Cuba decriminalized attempts to leave the country illegally.

The agreement forced Cuban would-be migrants to anchor their rafts. They then began to pay as much as US $ 10,000 for a spot on speedboats arriving from Miami or Mexico, with engines and radars capable of evading Cuba’s border patrol and the US Coast Guard.

That, however, is the end of a story that began in 1994, with a rumor: people then said that ships from Miami would dock in Havana to pick up anyone who wanted to leave the country, as they did at the port of Mariel in 1980.

The news came at the worst time for Cuba’s economy, when the country had hit rock bottom and people suffered brutal food shortages, had virtually no clothing or shoes and endured power cuts that lasted more than 8 hours, as well as the complete collapse of public transportation.

The dramatic collapse of East European socialism removed any hope of rescue from the horizon. At the time, no one dreamed that, in Latin America, governments sympathetic to Cuba would come to power or that Hugo Chavez would become president of Venezuela.

Cuba Burning

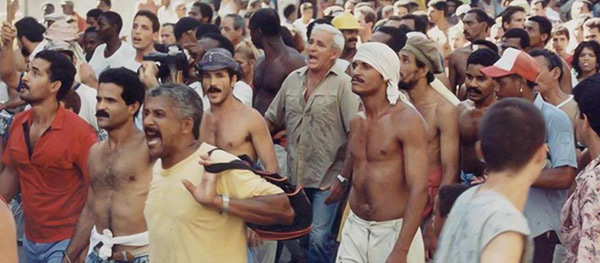

People had been running out to the streets of Old Havana and Centro Habana since the morning of August 5, spurred by announcements that the ships had arrived, but they would invariably run into a chain of police officers that prevented them from reaching the port.

I never saw what spark set off the explosion, but, as I was driving down San Lazaro, violence suddenly broke out. People lunged towards the police, throwing stones at them, while the officers fired their guns into the air, failing to frighten anyone away.

The anti-riot squads of socialism – construction workers armed with metal rods and sticks – arrived shortly afterwards. It was the most violent confrontation I have ever seen in Cuba, and it looked as if it was never going to end, because neither side was willing give ground.

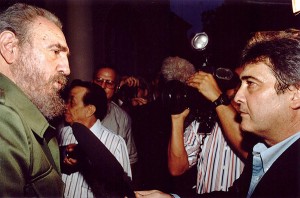

Suddenly, in the midst of all the commotion, Fidel Castro and Felipe Perez Roque appeared, walking alone. Like a movie that had been put on pause, everything froze for an instant. After the initial shock wore off, Fidel’s followers began to cheer and his opponents ceased throwing stones.

When he was half a meter away from the journalists, his bodyguards showed up and, almost by force, lifted him up into a jeep whose top had been folded down. He rode down Havana’s ocean drive this way, telling the gringos he would stop looking after their border if Miami radio stations continue to spread such rumors.

Some hours later, the US diplomatic chief in Cuba made the mistake of threatening Castro. It was more than enough. Castro went on national television to announce that Cuban borders were now open to anyone who wanted to leave the country.

Thousands of rafts began to be built at full steam. Some were built on the coast, others were taken from different neighborhoods to the ocean drive. The price of inner tubes, large plastic bottles, canvas, Styrofoam and compasses skyrocketed.

It had been 14 years since the Mariel exodus and Cubans were slightly better people: no one threw eggs or insulted or attacked anyone. On the contrary, there was an abundance of hugs, tears and wishes for a safe journey. There were even farewell parties.

Washington warned the rafters they would be confined in the Guantanamo Military Base – and kept its promise – but that did not discourage them. A neighbor of mine, an electrician, was taken to a base in Panama, where they had a brawl with the marines and ended up in the slammer.

When President Clinton understood none of his threats would put an end to the flow of Cuban migrants, he sat down to negotiate with Havana and, months later, signed the migratory accords that continue to be in effect today.

By then, 35 thousand Cubans, including many who had protested on the street, thrown stones at hotels and confronted the police, had already left the country. Washington had rid Fidel Castro of his most violent opposition, determined and radical at the toughest time faced by the revolution.

Translation: Havana Times