As economy improves, the face of hunger doesn’t change

Three weeks ago the mother of Steve Owen’s son showed up and unloaded a bunch of bags. He’s all yours, she said. I can’t handle it any more. What else could Owen do but rearrange his life?

That meant Owen needed a new apartment for him and his 6-year-old son. A new apartment requires a deposit; then there are deposits for electricity and gas. With part-time pay as a counselor at Everest University in Largo, that doesn’t leave much for groceries.

Last week, Owen, 46, waited for his first time with more than 30 other people at the Daystar Life Center in St. Petersburg. The center provides many services, but mostly its volunteers hand out donated food and groceries.

Owen took a number — 14 — and sat in a red seat, waiting so he could feed his son.

Owen took a number — 14 — and sat in a red seat, waiting so he could feed his son.

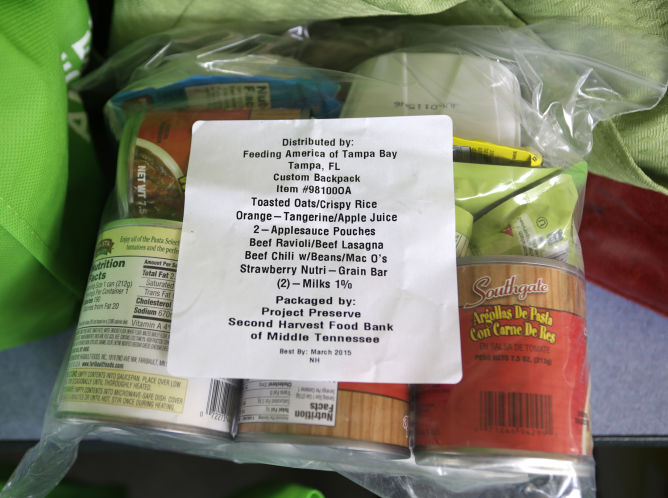

Feeding America, a national food bank, recently published a report on the state of America’s hungry. The local chapter supplies Daystar with some of its food. And Daystar’s lobby is a representation of the report’s latest findings, a much different picture than what typically comes to mind.

In Tampa Bay, few of Feeding America’s clients are homeless. About 23 percent own their own home, and 70 percent rent. Almost half have completed high school and 29 percent have at least some college experience.

While the unemployment rate across the nation has decreased in recent years, many people still struggle with part-time work or low wages. In 2012, the poverty rate across the nation was 15 percent.

“This is the largest number living in poverty since statistics were first published more than 50 years ago,” the Feeding America report reads.

And many are children.

On Friday, kids at Gibsonton Elementary School in Hills- borough County picked up loaves of bread and boxes of cereal and juice from Feeding America volunteers.

Amanda Figueroa’s 10-year-old son, Vinny, started getting a weekly bag this year. Figueroa, 36, works full time at an insurance company. Her husband is a stay-at-home dad. The family doesn’t qualify for free or reduced lunch for Vinny.

“On paper we make too much money,” she said.

She gets paid every two weeks and the food helps get them through those times when bread runs out before the next paycheck comes and she has to choose between money for her son’s lunches and groceries for the house.

She gets paid every two weeks and the food helps get them through those times when bread runs out before the next paycheck comes and she has to choose between money for her son’s lunches and groceries for the house.

The food helps Conne Smith’s mother, who has custody of five of her great-grandchildren who attend Gibsonton Elementary. Smith, 50, said her mother is on a fixed income and receives Social Security.

“Even with public assistance, with bills and school, clothes and shoes, there’s always times with five little kids when you run out of stuff,” Smith said.

In Florida, 17 percent of the population is considered food insecure, meaning their access to food was unstable. Feeding America Tampa Bay, which services 10 counties, helps to feed 841,000 people and 282,000 households each year.

One in six residents receives help from the group. They are mostly families forced to choose between rent, utilities, gas in the car or groceries. They work part-time or are underpaid.

Tampa Bay’s hungry are much like Owen, the Daystar client who got his first food assistance last week.

Beside him sat a mother with a baby carrier she rocked with her foot. Across from her waited an elderly man. Near the doorway crowded a mother and her four daughters.

Owen’s black-frame glasses hung from the collar of his T-shirt as he sat back in the chair; his number tucked under his big hands. He thought about his son.

“Even if I don’t eat, he has to eat,” Owen said.

Owen makes about $16,000 a year. He’s enrolled at Everest and working toward a business degree. He hopes for a full-time position as a counselor and the accompanying salary. When will this happen?

“I’m on the faith time line,” Owen said. He looked up to the ceiling and beyond. “Everything I need He’s going to give me when He’s ready.”

Daystar helps about 80 people each day. There’s no busy season. People are always hungry. They line up before the doors open at 8:15, and knock on the door after closing at 3. They fill metal racks with cans of black beans, green beans, garbanzo beans, tomato sauce. The produce waits in paper bags. The meat in the freezer is always the first to go.

A worker walked into the lobby. Today they are understaffed and the seats are full. The woman said there might be a bit of a wait.

“Number 11!” a clerk called out.

Three more until she called Owen’s number. He could wait as long as it would take. As long as his son ate.

(From the: Tampa Bay)