Diplomat foresees an end to the embargo

From the Cuban daily Granma

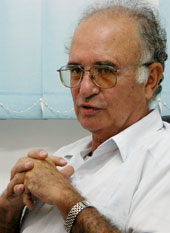

The newspaper Granma published an interview with Ramón Sánchez-Parodi Montoto, former director of the Cuban Interests Section in Washington (1977-1989), vice minister of Foreign Relations until 1994 and Cuba’s ambassador to Brazil until 2000. He wrote the book “Cuba-U.S.: A 10-time relationship.” Progreso Weekly has translated excerpts of the interview that are pertinent to the present situation between the two countries. Clarifications by the translator appear [in brackets].

—At the time when the Interests Sections were opened [in 1977], did anyone think that the dialogue would advance further, that they’d become embassies?

—Yes, both they and us. But the circumstances were always very complex and there were many opposing interests.

Reagan himself was actively promoting accords with Cuba, such as the immigration accords of 1984, which had been interrupted earlier. Not only did he promote them but also, when a memorandum of understanding was reached, it was the White House, not the State Department, who made the announcement, which gave it a hierarchy it hadn’t had before. This demonstrates that there had always been an interest on its part. Even Carter’s presidential instruction in March 1977 clearly says, “to normalize relations with Cuba.”

—Then why was normalization not achieved?

–Among other things, there had been contradictions inside the Carter administration that were expressed in foreign policy, not only with relation to Cuba but also to Iran and the Soviet Union. At the same time, there was the issue of Africa, where we had opposing interests, plus the processes of armed insurrection in Latin America, especially in Nicaragua.

–So the moment when we were closest to normalizing the relationship was with Carter?

–Sure, because it was he who made the decision to normalize the relations.

–Haven’t we gone through any similar moments since then?

–I don’t believe so. We thought it would happen with Barack Obama, but he – once he was sure of being nominated as the Democratic candidate in 2008 – really began to shift toward the center, to move closer to conservative positions.

Obama has never been, in any sense, on a search mission to normalize relations. His policy is a “lite” version of the policy of George W. Bush [Jr.] It has not changed. That’s linked to other complications the United States has, which particularly influence his policy toward Latin America.

By now, the foundations of U.S. policy, the instruments of that policy in the region, reflected on the idea of the inter-American system, have been blown to pieces. They have to rethink their future policy toward Latin America.

–During the years when you headed the Interests Section, which were the most tense moments of the relationship?

–From the point of view of hostility, the most tense moments unquestionably came at the start of the Reagan administration. Among other things, because he had a project to push back the process of normalization as part of his design for foreign policy, and everything that followed as an expression of the ideas of the New Right.

Particularly because of the very clear stance of [Secretary of State] Alexander Haig to promote even a military attack against Cuba. He proposed that to Reagan.

—Was a military attack always kept as an option?

–Yes, the policy of the United States toward Cuba is a policy of State.

Reagan acted more sensibly and rejected Haig’s proposal. I would say that that was the moment of greatest tension. Fidel has commented to me that perhaps one of the things that saved us from a military confrontation was the assassination attempt on Reagan [in March 1981].

There were moments of tension also during the events in Mariel, but that was rather political tension and we had the capacity to act.

–You have insisted more than once that U.S. policy toward Cuba is a policy of State. Then, do you disagree with those who say that the policy toward Cuba is directed by the Cuban-American lobby in Florida?

–That has nothing to do with it. We have publicized it a lot, but that is against all logic and reality. In the first place, the term “Cuban-American” is one of the things we do when using the U.S. terms and we take them as absolute truth.

That is a Census term describing social groups. A Cuban-American is someone who writes on the Census sheet that he is a Cuban-American. But, what do Ted Cruz or Marco Rubio have to do with Cuba?

Now then, even if we accept the term, what weight do they carry in the elections? In the Florida counties that have Cuban-Americans, the Democrats have won since 1992, and almost always since 1960 until today.

–There are some powerful ones, like Ileana Ros-Lehtinen…

–But what did she do against Cuba during the time she headed the House Foreign Relations Committee? Zero.

When the Cubans who controlled Cuban society, Cuban politics, the economy, business, everything in Cuba were here, the only thing they could do was what the “yanquis” told them to do. And now that they have nothing in Cuba, and they know it, what do they do?

We often fall into the trap of taking the arguments of the United States and their explanations as true, whereas they are false. That doesn’t mean that the topic of Cuban emigration is not important for us, and we have to solve it in terms of our interests.

When the [oil platform] Scarabeus came, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, Mario and Lincoln Díaz-Balart sent an open letter to Obama arguing that it was against the blockade and American interests and urged the president to do something. Obama paid them no mind. They have no strength. They’re being used.

—To maintain the policy of State…

–And the policy of State is clear. The presidential proclamation that established the blockade, the Helms-Burton Law, the decision to put all that in the federal code, the OFAC [Office of Foreign Assets Control] and the actions against Cuba, all that is a policy of State. To change it, there would have to be a willingness on the part of the governments and the institutions, and that’s missing.

—Why do they need to change it?

–How is the United States going to resolve its policy toward Latin America without resolving its relations with Cuba? We maintain full relations with all the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and even with the United States we have diplomatic links. And that was the region where the United States advanced the most in its policy of isolation.

These countries are not going to change their policy toward Cuba. They already said that there won’t be a Summit of the Americas — which will be in Panama in 2015 — if Cuba doesn’t participate. What will the United States do?

–Do you see the time near for a normalization of relations?

–That doesn’t exist as such, and the lifting of the blockade is not a decree; it’s a process that can take many years. Some things are being done, for example, the current discussion about the issue of mail.

But even if someone says “the blockade has been eliminated,” relations worldwide are regulated by the series of bilateral or multilateral accords that would have to be negotiated between Cuba and the United States.

For example, air communications, what becomes of Radio Martí, how will the visas be handled, the consular fees, all that has to be negotiated and all that takes a long while, considering our interests and theirs.

Of course, the day the United States says, “the Torricelli and Helms-Burton laws have been eliminated, Kennedy’s presidential proclamation has been abrogated,” all that will have a very big impact, huge.

I don’t think that that will happen with Obama. Maybe it will happen in the next presidential terms, be they Republican or Democrat, because we err again when we think that it will happen with the Democrats. Direct conversations began with Nixon and Kissinger, no less.

I believe that the conditions are ripe, because they can’t bear it any longer.

–So, even if it doesn’t happen under Obama, do you think that an advance toward rapprochement will occur later?

–Fact is, some forward motion is occurring. And the political times are in favor of the elimination of the blockade. The United States is in a crisis situation and, as I told you, it has to redesign its policy toward Latin America, which should not be on the basis of the inter-American system. Besides, 188 countries voting [in the United Nations] to eliminate the blockade means total isolation.

The objective of U.S. policy toward Cuba is to restore its domination and they won’t be satisfied with less than that.

I do believe that — if not in the next administration, maybe in the following one — a substantial decision must be made toward normalizing relations with Cuba. The easiest step, one that most strongly propels a change, is for the United States to say that all prohibitions banning the travel of U.S. citizens to Cuba are eliminated. That will obligate [Washington] to transform the terms of the blockade.

–The United States and Cuba have never had a fully normal relationship. There was a long period of dependency and later a hostile relationship or an absent relationship. How would a normal relationship be, then?

–It is not normal, what would be a normal relationship. It would be a relationship that’s beneficial to both countries. But it has to be void of any attempt to dominate, [a relationship] like the ones we have with lots of countries. And that doesn’t mean that eventual conflicts won’t happen. Our political and economic system is not an obstacle to maintaining normal relations with anyone.

–And do you think that at some point they will renounce their intention to dominate?

–If they don’t renounce that, there will be no normal relationship. For more than half a century, they have been shown that any attempt to restore that domination has failed.