Cuba spending hovers around $1 billion

The State Department, the Agency for International Development and the National Endowment for Democracy have spent $304,300,000 on Cuba-related democracy programs since 1996.

The Broadcasting Board of Governors, which oversees Radio & TV Martí, has spent another $700 million or so. That brings the total to around $1 billion.

USAID and the State Department have spent nearly 90 percent of the Cuba money since 2004. That was a year after then-President George W. Bush created the Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba and declared that he was ready for “the happy day when the Castro regime is no more.”

Fidel Castro was president of Cuba back then. Roger Noriega, then assistant secretary of state, said, “The United States…..will not accept a succession scenario.”

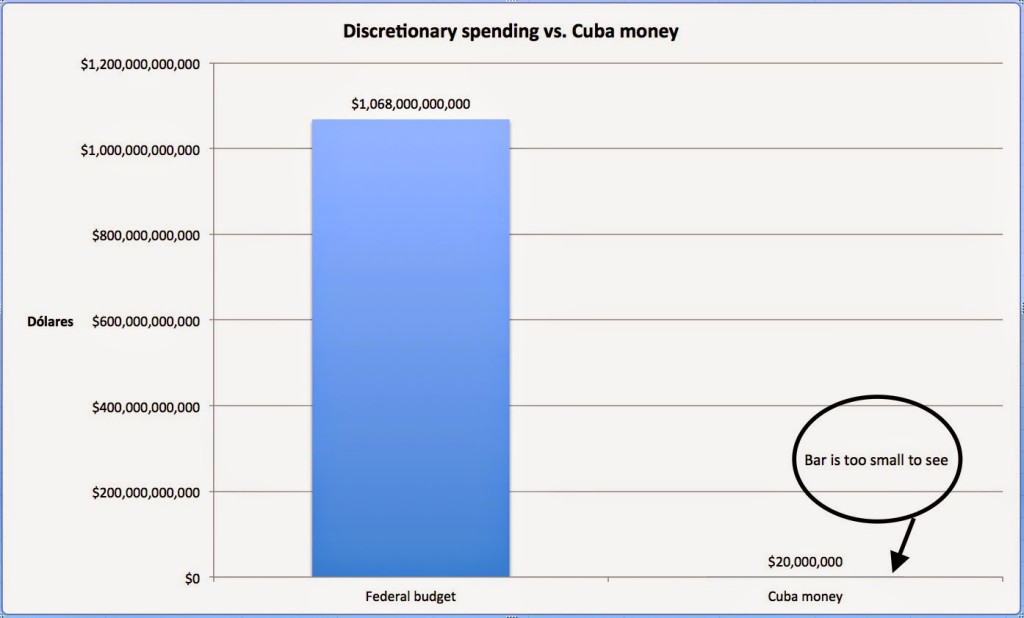

More than a decade later, the democracy programs endure. The State Department plans to spend $20 million on the programs in 2016. That’s a tiny fraction of the federal government’s proposed $1,168 trillion discretionary budget, which excludes Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid.

But the money has outsized impact in Cuba, where the socialist government demands that the U.S. end such programs as the two nations restore diplomatic ties.

When I traveled to Cuba in December, some Cubans asked me how it is that the U.S. government runs democracy programs that Cuban officials see as provocative and illegal while negotiating to restore diplomatic relations.

I tell them it’s democracy in action. Strong political interests demand that the U.S. pressure Cuba to adopt democratic reforms. At the same time, many Americans press for normalized relations with Cuba. The U.S. government’s response is to push for both democracy and restored ties.

Some Cubans have told me the U.S. approach seems contradictory – and maybe it is – but it’s also an example of the squeaky wheel getting the grease.

It reminds me of what I saw while covering immigration along the U.S.-Mexico border in the ’90s. The U.S. beefed up border enforcement while failing to crack down on employers who hired undocumented immigrants. It was a schizophrenic approach, but it underscored how the political system responded both to employers who wanted cheap labor and citizens who demanded an end to illegal immigration.

The U.S. government operates Cuban democracy programs under Section 109 of the 1996 Helms-Burton Act.

The act seeks a transitional government that would lead to “a democratically elected government in Cuba.”

It also forbids the U.S. president from ending sanctions unless he decides that Cuba has met a series of requirements. These include:

- Agreeing to free and fair elections within 18 months after a transitional government takes power.

- Forming a government that does not include Fidel or Raul Castro.

- Legalizing all political activity.

- Dissolving its state security forces.

- Releasing all political prisoners and opening prisons to human rights investigators.

- Allowing multiple independent political parties equal access to the media.

- Ending jamming of Radio and TV Martí broadcasts.

- Taking steps to return property seized from U.S. citizens after the 1959 revolution.

Supporters of U.S. policy tell me that the American government has the right to impose its will because the Cuban government is a dictatorship that has no moral authority and no right to deprive its citizens of universal human rights.

Critics of U.S. policy say that the U.S. has always tried to control Cuba’s fate. They cite then-Secretary of State Colin Powell’s first report to the Free Cuba commission in May 2004. It showed U.S. officials were planning every last detail of Cuba’s future. The report said that if Cuba’s transitional government requested help, the U.S. government was prepared to:

- Provide dam safety training, in Spanish

- Simplify the sale of refurbished U.S. locomotives to Cuba

- Help map coral reef systems and assess fish habitat

- Give advice on how to add trails and other infrastructure to prime bird watching spots

As the U.S. and Cuba negotiate, I wonder what has become of the U.S. government’s many transition plans for Cuba.

USAID’s Cuba programs are scheduled to end in September. The agency has three current partners:

- Grupo de Apoyo a la Democracia

- International Republican Institute

- New America Foundation

The Pan American Development Foundation finished its work in March, according to USAID. I filed a Freedom of Information Act request for information on PADF’s work 1,278 days ago and still have not gotten a response from USAID.

Following the money isn’t easy. USAID’s partners funnel 40 percent of their funds, on average, to subcontractors.

USAID does not reveal the names of subcontractors, despite President Obama’s promise that the U.S. government would begin naming subcontractors.

USAID’s partners use an average of 12 subcontractors each. One partner had 38 subcontracts for a single Cuba contract.

The partners pay subcontractors anywhere from $5,000 to $300,000.

The partners pay subcontractors anywhere from $5,000 to $300,000.

From 1996 to 2012, USAID and the State Department awarded 111 Cuba-related contracts and grants to 51 partners.

If there were 12 subcontractors for each contract – and that’s the average – that means there were 1,332 Cuba-related programs from 1996 to 2012.

USAID’s penchant for secrecy makes me wonder whether the agency will try to keep a hand in Cuba – off the books – perhaps through its Office of Transition Initiatives. (See “Another ‘window of opportunity’ for OTI?“).

The State Department has not been any better than USAID in responding to FOIAs. The department passes along most of its Cuba money to the NED, which recently stopped disclosing its grant recipients. (See “Sudden Secrecy at NED“).

USAID and the State Department spent $264,300,000 on Cuba programs from 1996 to 2014. They set aside $20 million for 2015. The NED spent another $20 million or so from 2006 to 2014. That totals $304,300,000.

Add the $20 million planned for 2016 and it’s $324,300,000.

Less than 15 percent – and that’s a generous estimate – reaches the hands of Cuban dissidents and human rights activists who put their lives and their freedom at risk.

Most of the money goes toward salaries, office expenses and travel, tax records show.

(From: Along the Malecón)