The Rogovins and their family photos

HAVANA — Paula Rogovin still remembers that episode of her childhood in Buffalo, N.Y., when she interrupted the lesson at school by raising her hand and saying, “I think that Cuba is nice.”

That’s what she heard Ann and Milton say, her “progressive” parents, in the warm safety of home. But on that day she learned that, outside the home, she ought not to speak of certain subjects, as true as they might seem to her, because everywhere in this world the ruling power silences, rephrases, changes or twists reality for its own convenience. And going against it is, at the very least, complicated.

The “progressiveness” of Paula’s parents was communism behind a less-alarming word. To call oneself a communist in the United States in the 1980s was as suicidal as confessing in Cuba — economically throttled by the Special Period — that you were willing to leave the country on a boat or whatever to give your family a more prosperous future. In the U.S. they could fire you from your job and socially alienate you; here, more or less the same, and fling eggs at you, too.

The topic of U.S.-Cuba relations has more angles than a hexahedron. There’s enough shadings to make soup with, truths that outshine all imaginable fiction. There are people on both sides of the Straits (which may be the lowest barrier that separates us) with their own stories to tell. And there’s not a shore, none, that can hold the entire reason.

Ann and Milton, Paula’s “progressive” (communist) parents, crossed the borders of incomprehension three times between 1986 and 1989. They came with the aid of friends in the Revolution, escaping through Mexico, Canada and other third countries to become directly acquainted with “The Red Hell.”

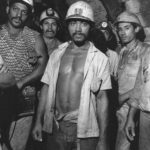

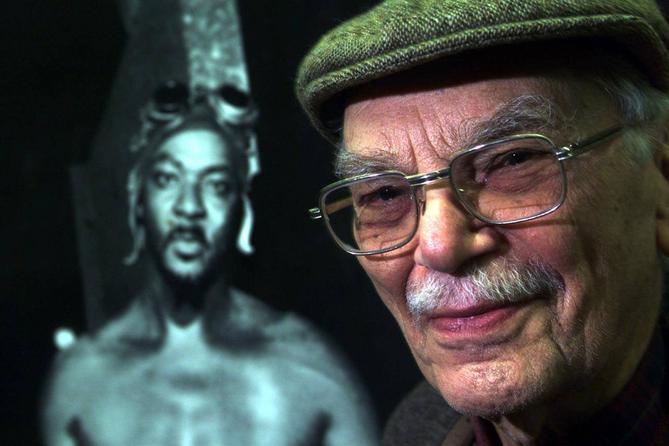

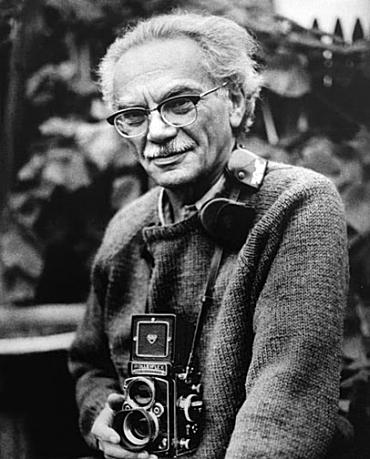

Milton, an optometrist by trade, wore different eyeglasses, of planetary gradation, to see the entire world as it really was. Camera in hand, he went into the farthest corners of Cuba and ended up in Moa, a red-soiled and remote region of Holguín, in eastern Cuba, where the extraction of ore buttressed the country’s economy.

“For a long time, Dad had been taking pictures to defend, through art, the causes that he and my mother had decided to embrace — the causes of working families, indigenous minorities, the workers,” Paula says today.

“He began with the native reservations that survived outside our hometown, Buffalo, and then traveled to places like Czechoslovakia and Mexico to do a series on the working class, that large mass of forgotten people to whom (he always told me) the big cities owe their glamour and impeccable functioning.

“Then he learned about the mines in Cuba, about this particular place in Holguín, and decided to include the faces of Moenses.”

As Cuban troubadour Carlitos Varela sang some time ago in a powerful song, “behind all governments, behind those that are no longer here, there is a family picture.” Everyone keeps his own photograph, that living, real, painful and honest reminder of what has been an inner segment of his life, beyond the speeches.

The photos of Paula’s family are varied and many, a visual rosary of unknown faces, contorted by effort and the heat. After each trip, they became the only souvenirs in her parents’ hands.

“My parents were not ordinary tourists. In fact, they traveled not to relax, not to stop in their struggle. I couldn’t really tell you how they did it, how they managed to contact so many people in so many parts of the world at a time when there was no Internet or anything like it. The girl I was and the woman I am owe them much respect for their greatness in that regard.

“She was a teacher; he, a simple optometrist. Nobody could think of them as big intellectuals, but they taught my siblings and me the ideals of social justice, of altruism, and the irrenounceable need to defend the defenseless.” Almost 30 years later, it is Paula who visits Cuba.

“So many things are changing,” she sighs, contentedly. “Now, at last, I can come with a person-to-person visa, with my friend Wendy, to learn about this country that enchanted my Mom and Dad.

“Wherever I look I seem to see her, with her eyes filled with tears. Standing in front of a hospital or a university or a grand theater, discovering how a country that poor could give its citizens their dreams of health, education and culture, public and free at all levels, the dreams that both my parents used to call for, while carrying signs in demonstrations and peaceful marches back in the United States.”

The daughter of Ann and Milton has discarded the idea of a hotel and is staying at the home of Rolando and Emilia, a couple who rent rooms to foreign visitors.

“I am interested in meeting ordinary Cubans, like those my parents photographed. People like Rolando, who can tell me about his participation in the war in Angola; or like his wife Emilia, who can explain to me what it’s like to be left alone with four children while your husband fights for the freedom of another country.”

Paula will be in Havana only a couple of days, enough for the presentation of her father’s photo collection at the Institute of Friendship with Peoples (ICAP). The pictures will later be sent on a tour of all the Cuban provinces.

In only 10 days, she will travel through Pinar del Río, Santiago de Cuba and — of course — Holguín, because “I can’t leave here without greeting the miners, without meeting the working families in Moa. That’s my greatest desire.”

“I will also take my souvenirs home,” Paula says. “Back in my country, I’ll be able to tell about the time that my tour guide fell ill and was taken to the clinic, where a nurse had to use a latex glove as a tourniquet to inject his medicine. Yes, I will agree that Cuba lacks many things but that Cubans have much ingenuity and creativity to overcome the problems. And there’s a great desire to pull ahead.

“I will tell that you can go into a paladar and end up talking for an hour with the owner about national and international politics, because the man is a professional in another line of business who has had to set up a private restaurant to improve his life but who is still interested in discussing the complex issues of his nation and the world.

“And to the children I teach at my public school in New York, to my kindergarten kids, I will take (as my father did) pictures, pictures that speak for themselves. Photographs of the cane and banana fields in Pinar del Río, so they may learn that fruits don’t come from the supermarket but from the earth. Photographs of Cuban children, dancing or playing baseball, so they may learn that nearby there is a country that’s different but that’s a place where they can find new friends.”

A simple tourist camera is often the best of bridges. An honest picture can be the most faithful and sober speech. The Rogovin family knows all about that.