College athletes must unite to stop exploitation

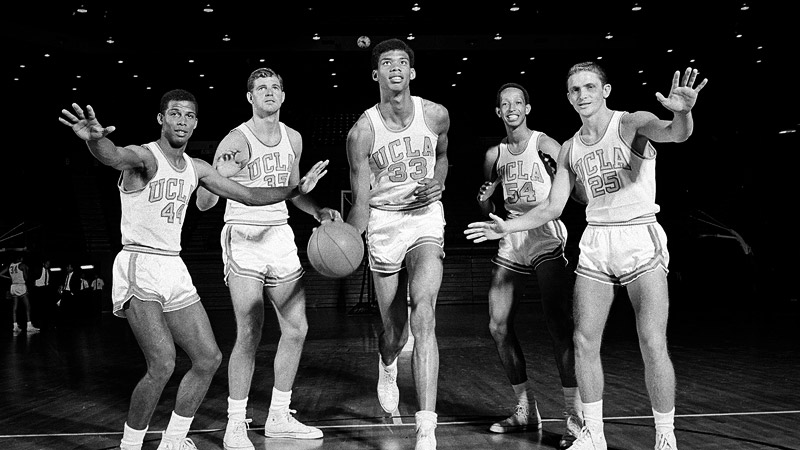

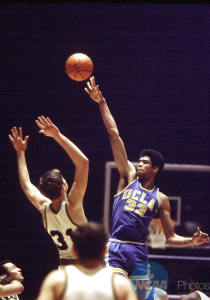

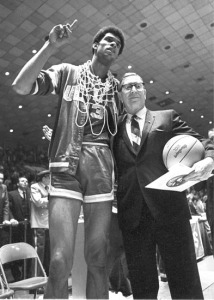

When I played basketball for UCLA, I learned the hard way how the NCAA’s refusal to pay college athletes impacted our daily lives. Despite the hours I put in every day, practicing, learning plays, and traveling around the country to play games, and despite the millions of dollars our team generated for UCLA — both in cash and in recruiting students to attend the university — I was always too broke to do much but study, practice, and play.

What little money I did have came from spring break and summer jobs. For a couple summers, Mike Frankovich, president of Columbia Pictures and a former UCLA quarterback, hired me to do publicity for his movies, most memorably Cat Ballou (which was nominated for five Academy Awards).

In 1968, I needed to earn enough summer money to get through my senior year. So, instead of playing in the Summer Olympics, I took a job in New York City with Operation Sports Rescue, in which I traveled around the city encouraging kids to go to college. Spring breaks I worked as a groundskeeper on the UCLA campus or in their steam plant repairing plumbing and electrical problems. No partying in Cabo San Lucas for me. Pulling weeds and swapping fuses was my glamorous life.

Despite my jobs, every semester was a financial struggle. So in order to raise enough money to get through my junior and senior years, I let Sam Gilbert, the wealthy godfather of a friend of mine, scalp my season tickets to his rich friends. This brought me a couple thousand dollars. Spread out over a year, it was still barely enough to survive. I was walking out on the court a hero, but into my bedroom a pauper.

Naturally, I felt exploited and dissatisfied. In my first year, our freshman team beat the varsity team, who had just won the NCAA championship. We were the best team in the country, yet I was too broke to go out and celebrate. The more privileged students on academic scholarships were allowed to make money on the side, just not the athletes.

And unlike those with academic scholarships, if we were injured and couldn’t play anymore, we lost our scholarships but still had medical bills to worry about. We were only as valuable as our ability to tote that ball and lift that score.

Coach Wooden told us that there was no changing the NCAA’s minds, that they were “immovable, like the sun rising in the east.” I never personally encountered any players who cheated or shaved points, but I could see why some resorted to illegally working an extra job or accepting monetary gifts in order to get by.

The worst part is that nothing much has changed since my experience as a college athlete almost forty years ago. Well, one thing has changed: the NCAA, television broadcasters, and the colleges and universities are making a lot more money.

- The NCAA rakes in nearly $1 billion annually from its March Madness contract with CBS and Turner Broadcasting.

- The NCAA president made $1.7 million in 2012.

- The ten highest paid coaches in this year’s March Madness earn between $2,627,806 and $9,682,032.

Management argues that student-athletes receive academic scholarships and special training worth about $125,000. While that seems like generous compensation, it comes with some serious restrictions:

- College athletes on scholarship are not allowed to earn money beyond the scholarship. Yet students on academic scholarships are allowed to earn extra money.

- The NCAA allows the scholarship money to be applied only toward tuition, room and board, and required books. On average, this is about $3,200 short of what the student need.

- Academic scholarships provide for school supplies, transportation, and entertainment. Athletic scholarships do not.

- Athletic scholarships can be taken away if the player is injured and can’t contribute to the team anymore. He or she risks this possibility every game.

- The injustice worsens when we realize that the millionaire coaches are allowed to go out and earn extra money outside their contracts. Many do, acquiring hundreds of thousands of dollars a year beyond their already enormous salaries.

In this light, not only is the compensation inadequate to the effort and risk compared to academic scholarships, but there is a real chance that players may end up without an education, yet deeply in debt. Players who are seriously injured could technically make use of the NCAA’s catastrophic injury relief. This sounds fair and compassionate, except the policy doesn’t apply unless the medical expenses exceed $90,000 — which most claims don’t. If the student’s medical bills are $80,000, they’re on the hook for it themselves.

To protect against career-ending injuries, the NCAA also offers Student-Athlete Disability Insurance. Unfortunately, this only pays if the athlete can’t return to the sport at all. But most injuries can be repaired to some extent, even if the athlete is no longer as good and gets cut from the team. Only a dozen such claims have been successful over the past twenty years.

Life for student-athletes is no longer the quaint Americana fantasy of the homecoming bonfire and a celebration at the malt shop. It’s big business in which everyone is making money — everyone except the eighteen to twenty-one-year-old kids who every game risk permanent career-ending injuries.

It’s the kind of injustice that just shouldn’t sit right with American workers who face similar uncertainty every day.

Unfortunately, those with a stranglehold on the profits aren’t likely to give up their money just because it’s the right thing to do. Instead, they will trickle some out in a show of fairness and hope that it’s enough to keep the peasants from storming the castle. That’s what happened in a settlement earlier this year, when college football and basketball players whose likenesses have been used in sports video games — generating millions of dollars for other people — finally received compensation.

The NCAA’s power is further eroding thanks to the push to unionize college athletes, a necessary step in securing a living wage in the future. Without the power of collective bargaining, student-athletes will have no leverage in negotiating for fair treatment. History has proven that management will not be motivated to do the right thing just because it’s right. Unions aren’t all perfect, but they have done more to bring about equal opportunities and break down class barriers than any other institution.

We’re angry when we see a vulnerable group exploited for profit by big companies, when executives rake in big bucks while powerless workers barely scrape by. We were furious when it was reported that Nike made billions in 2001, while at the same time employing, through subcontracted companies, twelve-year-old Cambodian girls working sixteen-hour days for pennies an hour to make $120 shoes.

We were outraged again in 2006, when the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School reported that about two hundred children as young as eleven years old were sewing clothing for Hanes, Walmart, JC Penny, and Puma in a factory in Bangladesh.

The children sometimes were forced to work nineteen to twenty-hour shifts, slapped and beaten if they took too long in the bathroom, and paid pennies for their efforts. According to the report, “The workers say that if they could earn just thirty-six cents an hour, they could climb out of misery and into poverty, where they could live with a modicum of decency.”

Thirty-six cents an hour.

While such horrific and despicable conditions are rarer in the United States, we still have to be vigilant against all forms of exploitation so that by condoning one form, we don’t implicitly condone others. Which is why, in the name of fairness, we must bring an end to the indentured servitude of college athletes and start paying them what they are worth.

The August decision by a federal judge to issue an injunction against NCAA rules that ban athletes from earning money from the use of their names and likenesses in video games, also included television broadcasts. This in itself could do much to bring about the end of NCAA tyranny.

The NCAA is appealing the decision so the case could drag out for years. In the meantime, the student-athletes continue to play Oliver Twist approaching the Mr. Bumbles of collegiate sports, begging, “Please, sir, I want some more.”

(From Jacobin)