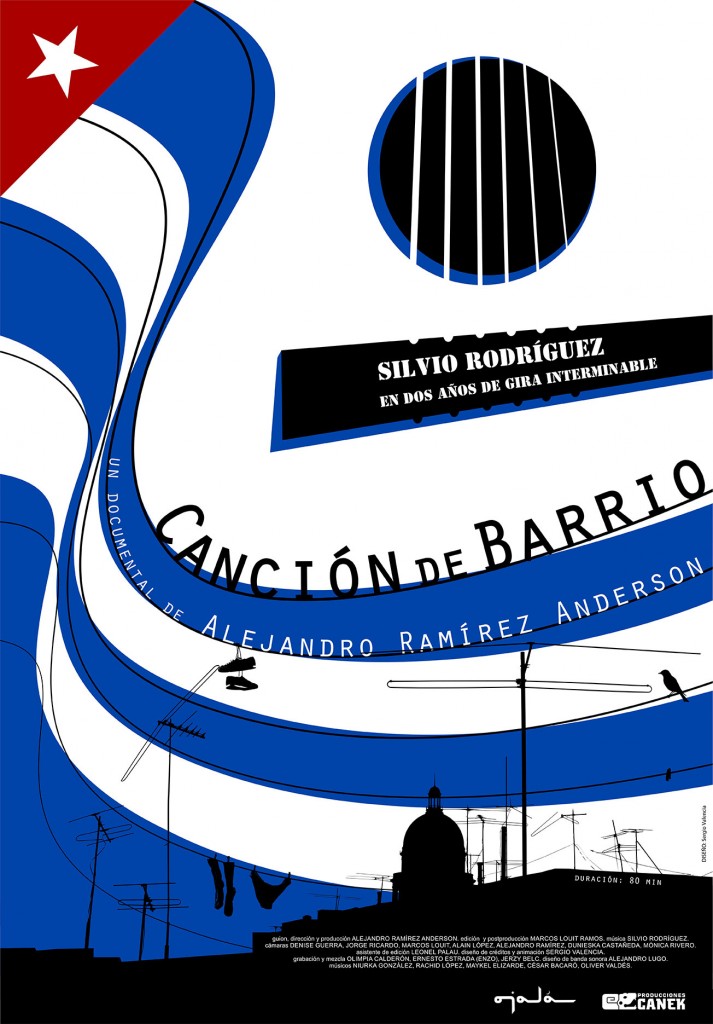

Barrio song

He was a strange man. Some years ago, he organized an expedition and went out to sow music in the places where unknown people suffer, in a Havana that has been filling with some poverty and some despair. Most of us haven’t been there, but this strange man compels us to see what he saw, to stop feigning ignorance.

In his Tour of the Barrios, Silvio Rodríguez took along a team led by a young documentary maker, Alejandro Ramírez Anderson, who, sharing the troubadour’s attitude, has turned the tour into a cinema story, a documentary, the experience of more than 30 concerts in the first two years of what has become known as the Interminable Tour.

Eighty minutes of indescribable emotion, which will be shown for the first time to the public in Barrio Song, premiering Aug. 28 at 8 p.m. at the Charles Chaplin Theater in this ailing yet dreamy Havana.

Milena Recio: What was the cornerstone of this documentary? How did it all begin?

Alejandro Ramírez: We began this work not knowing exactly what it would turn out to be, in the same way that Silvio began the tour without knowing that it would turn out to be the Tour of the Barrios and, well, as he himself called it, the Interminable Tour.

He began it one day at La Corbata, at the request of a police captain who was a Sector Chief. We filmed that first concert, then the second one, and the third. From that moment on, we realized that we were missing the most important aspect, which was neither the concert itself or Silvio’s presence but the situation of the residents of each of those places. And we allowed the idea to mature into what became the documentary.

He began it one day at La Corbata, at the request of a police captain who was a Sector Chief. We filmed that first concert, then the second one, and the third. From that moment on, we realized that we were missing the most important aspect, which was neither the concert itself or Silvio’s presence but the situation of the residents of each of those places. And we allowed the idea to mature into what became the documentary.

M.R.: What kind of images appear in the documentary? What kind of situations? Why in those barrios? Why does Silvio go to those barrios?

A.R.: The documentary focuses on the barrios of Havana that have deteriorated both physically and in terms of values. You will see the housewife, the CTC leader who in the afternoon must go fetch a couple of pails of water. Or the woman whose roof caved in two years ago during the hurricane and is living in the open air. I think it’s a broad map of situations, of the deterioration of those barrios and their problems.

M.R.: Why does Silvio, at this stage in this career, choose to devote time and effort to this project and, to a degree, use it to postpone other artistic commitments? How do you, as an artist, interpret that choice?

A.R.: The Tour of the Barrios is a continuation of Silvio’s work. To me, Silvio is an artist who has been very consistent with his way of being and his way of acting. Honestly, I’m not surprised that he’s doing the Tour of the Barrios, because he has always done things of this type.

We know the Tour of the Homeland and the Tour of the Prisons. The Tour of the Barrios comes at a sensitive time of crisis in the country.

M.R.: Do the songs provide relief? Do they relieve the poverty?

A.R.: I think they do. If you look at it pragmatically, during the concert the people disconnect, have a good time, dance, enjoy themselves, laugh, perhaps turn away from their daily problems. The problem is that this may be a one-time thing. Hopefully, this will create an echo and be imitated by other institutions and other artists, because I think that this is one of the functions of art.

M.R.: I dare to speculate about the fact that Silvio not only wants to provide relief for barrio residents who are in a situation of great social disadvantage, very acute in some cases, but also wants to make those spaces more visible. He wants the decision-makers to “step up and look.” Silvio may also have been trying a dialogue, a feedback, to make a comeback. Do you share my opinion?

A.R.: It would be a bit naïve to think that Silvio will arrive in a barrio and the situation will magically change. But Silvio is a privileged person at this time because many levels of our society can hear him, even levels of society to which ordinary people have no access. And the Tour of the Barrios has lifted the lid from many of those problems.

And it is odd, because these concerts are well attended, even though they’re not well promoted in the media. Also in the audience you find government officials, artists, intellectuals who often have not lived the experience of seeing these barrios, of entering them.

M.R.: How did you avoid a melodramatic vision — from the top downward — to illustrate the disadvantages?

A.R.: This is not the first time that we do a documentary or feature people who are socially disadvantaged. Being a documentary maker requires an attitude of simplicity, of profound simplicity. It is a relationship that must be established in a horizontal manner. The most important thing is to be sincere with the reality you are acknowledging.

M.R.: Out of everything you filmed, everything you experienced, in what you finally edited and left in the documentary — what pains you the most?

M.R.: Out of everything you filmed, everything you experienced, in what you finally edited and left in the documentary — what pains you the most?

A.R.: The situation of the elderly people. Many of them sacrificed themselves for this country and the revolutionary process. And at the end, taking everything into account, they gained nothing.

You might ask yourself, why not the children? The children are growing up in that situation and are developing their means of survival in that environment in ways that they’ll practice for the rest of their lives. Maybe they’ll go on to transform their environment. But I see old people in their 80s who don’t even have a roof over their heads. That is very sad.

M.R.: Out of everything you saw and experienced, what made you the happiest?

A.R.: Well, I think it was the hope that flowers amid the circumstances.

M.R.: We’re of the same generation and know what Silvio Rodríguez’s music meant for people who are 40 or 50 years old today. But Silvio is less and less heard in Cuba, and that’s probably because some of the values that he is exalting in his poetry, in his music, are “not very marketable,” to put it in so many words. How can people who no longer listen to Silvio and might be tired of not achieving their dreams identify with his music at this time?

A.R.: I don’t know. I wouldn’t know how to explain it, because that analysis you’ve just made is an analysis we have all made. But Silvio starts singing and the people start singing. Most of the children don’t know Silvio in person and ask us: “Who is Silvio?” However, everybody sings his songs and that’s a very impressive demonstration.

M.R.: If you had to write a brief summary to invite the people to see the documentary…

A.R.: The documentary has two very strong elements. One is the Tour itself and the role that Silvio, as an artist, is playing at this time, in this reality. The other is the raw reality of the Havana barrios, a reality that we often walk past, not realizing that it exists.

The documentary contains the experience of 34 concerts (in 34 barrios). At present, we’ve been in almost 60 barrios and in all we have found very similar situations.

M.R.: You come from a tradition of documentary work, where these topics — how communities live, what strategies have been developed to survive in conditions of disadvantage — interest you. What does this particular topic contribute to the trajectory you have followed as a person and a filmmaker? What Cuba is portrayed here?

A.R.: It is the first time that, as a team, we face more than 200 hours of recording. To deal with so many dramatic situations, so many charismatic characters, and then having to select has been a very difficult process.

On the other hand, I’ve looked at the documentary from a distance, and I don’t only think of its contribution to my career as a documentary maker. I see it and believe that it contains aspects of “Demoler,” “Una niña, una escuela” and “Monteros,” which are other documentaries I’ve made.

But I also see Alina Rodríguez’s documentary “Buscándote, Habana;” I see Karel Ducasse’s “Zona de silencio;” I see many documentaries that were made in the past 15 years. All those documentaries enriched me, before I came to this one.

Progreso Weekly shares an abridged version of this interview, published in full, in Spanish, in Progreso Semanal.