Assange, freedom and a mojito

HAVANA – His hair used to be blond but today it’s decidedly white. For more than 400 days, he has been confined in the Ecuadorean embassy in London, watched by plainclothes and uniformed policemen who prowl around the diplomatic building and by some very faithful friends who help him withstand his confinement.

No formal charge has been made against Julian Assange but his head is worth gold to the angry empires.

His only space of freedom continues to be the Internet. Through the net, with the great net, he keeps alive the Wikileaks project, which has brought many governments to public scrutiny and exposed the murderous practices and collateral homicides that the U.S. Army has committed in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Hundred of thousands of revealed documents compose these open archives of history, as well as the more recent history that Wikileaks shares. All this thanks to the “infidence” of people like Bradley (Chelsea) Manning and Edward Snowden, who also have become victims of the wounded beast.

The Internet allowed Assange to “fly” to Havana on Sept. 26, evading surveillance, controls and espionage, to be the guest of honor in a dialogue with journalists, bloggers and young journalism students who ended up, as usual, seated on the floor, tweeting.

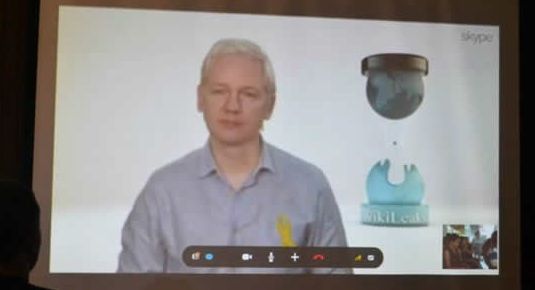

At 12 noon sharp, his image was projected on a screen. Skype made possible a real-time connection that brought his voice from London and gave visual body to a remote icon that the mass media have tried to turn into a kind of Hollywood illusion.

When he finally appeared, this global man wore on his chest an amazing yellow ribbon that defined the course of the whole exchange.

The ribbon was a symbol of his faith in life. I’m still here, I continue to fight – it seemed to mean – and I’m aware of what you wish to obtain with this ribbon. It was his best way to say “good afternoon” to the small group of Cubans who cheered him as if he were a celebrity and admired him as the hero he is.

Assange identified the blockade against Cuba with the blockade being enforced against Wikileaks. He compared his confinement with the imprisonment of the five Cubans who penetrated terrorist organizations in Florida and were therefore submitted to political trials and given disproportionate sentences. Four of them still suffer sadistic punishment in the United States.

In the small hall where cyberspace made possible our contact with Assange, a major Mexican journalist served as bridge to channel an intense traffic of expressions of solidarity.

Pedro Miguel of the newspaper La Jornada, who was the contact that Wikileaks chose to detonate the Mexican “cablegate,” delivered a magnificent closing, thanking Julian and the audience, whom he praised for their journalistic passion and their technological skills.

“We would have liked to be hundreds or thousands, but the technical limitations, partly due to the blockade, thwarted that desire. What you have told us will remain in the hearts and minds of all these people,” Miguel told Assange.

There was an explosion of laughter when Pedro Miguel issued very special thanks to Barack Obama, “who we know is listening to us,” for not interrupting the press conference.

“Of course you won’t be tried in the United States,” Pedro Miguel assured Assange, “because there are societies that are supporting the cause of Wikileaks and yours. I hope that soon you can take a plane from Quito to Havana, because we have to have a drink in this marvelous city.”

Progreso Semanal/Weekly authorizes the total or partial reproduction of the articles by our journalists, so long as source and author are identified.