Public, free education must remain untouchable

HAVANA – Every morning Juan and Maria meet in the schoolyard and greet each other as if they had spent a whole week (since last afternoon) without being able to see each other. Juan is a mulatto and the only child of a successful folk dancer who is always on tour in Europe, so his grandmother, a former dancer herself takes him to school. Maria does not know how to dance. She is a yogurt-colored, white girl and her mother is a researcher with a regular schedule at the Biotech Institute. Her father, a rock star with one of Cuba’s leading heavy metal bands, brings her to school.

Becky’s already there when Juan and Maria arrive. They live in the same Vedado neighborhood and only three blocks from where the school is situated, while Becky comes from afar, on the other side of the bridge over the Almendares River. She is brought to school by her dad, who is an evangelical Christian, those who always wear serious-colored pants and long-sleeved shirts buttoned to the top. The three of them — the grandmother and the two parents — always greet each other with hugs and kisses as if they also haven’t seen each other for weeks. Meanwhile the children borrow their parent’s cell phones to connect by Zapya and play the same games over and over again.

Moments later, but never at the same time — sometimes sooner, other times later — in walks the girl with the long, blonde braid carrying a brightly colored backpack. Her mother walks behind her talking on WhatsApp, and all parents leave what they’re doing to look at her in silence when she crosses their path. She is a young art curator who is constantly setting up exhibits and installations. She is always dressed in tight, sporty clothing because after dropping off her daughter she heads to the gym, or a yoga or pilates class.

Lastly, the executive arrives with his son, who gets out of an air-conditioned car he does not want to get out of because of the cool air inside. He then hardly greets anyone when he closes the door of his father’s Hyundai. He runs across the schoolyard looking for the girl with the blonde braid to ask if she did her math homework because he had not finished it — he didn’t understand a thing.

And finally, but never late, Charlie the policeman appears with his white captain’s chevrons on his shirt and his son on his right hand. He greets the parents with a bit too-strong handshake while smiling sweetly at the mothers.

Last, but not least, when all other children have arrived, comes the smartest girl in the school, always alone, because hers is a single mom who has being working hard since early in the morning, sweeping and cleaning other people’s houses.

Of course there are others who come: the son of the mason, the son of the taxi driver, the daughter of the secretary, the farmworker’s kid, the nurse’s daughter, the carpenter’s son, the doctor’s twins, and so on.

Twice a day they all see each other at the school when they drop off the children and at twenty past four, when they come pick them up. They take advantage of those moments before the bell rings for the start or end of the school day to tell each other about their lives, seek solutions to some problem, to ask at what store they found chicken, or where they can find puppies, and if the tomato paste has finally reappeared. That’s how their children see them each morning and late afternoon: together and scrambled amongst each other, laughing and conversing as equals, like regular people.

They see them and imitate them: they talk to each other, play among themselves, learn each other’s peculiarities, discover similarities and their differences, their advantages and disadvantages. In other words, they grow. More importantly, these people who may never have looked or talked to each other help their children with homework, spend time with them at home while studying, creating a type of teamwork and collaboration for the party at the end of the school year.

This and so many other things passed through my mind when I heard that my son’s friend would not be returning to this school because for some irrelevant reason his family had enrolled him in the private Spanish school in Miramar. So overnight the little man changed class, and Class. I’m not sure, but I doubt diversity reigns in the new place.

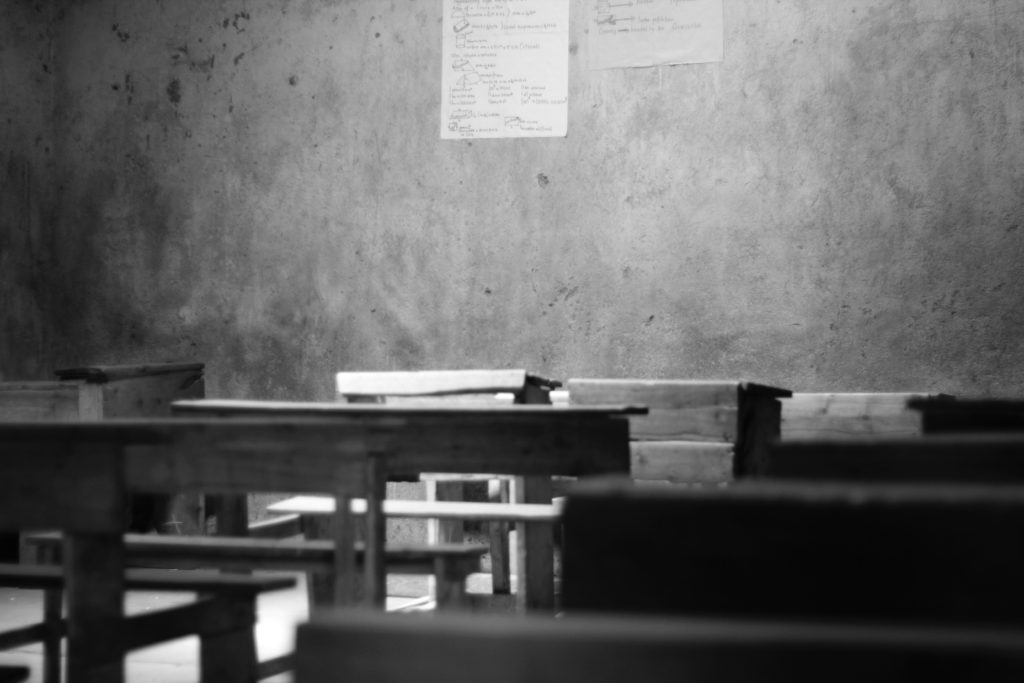

As many things as we need to change for the better, there are quasi-sacred matters that should remain immovable, untouchable. One of those things is free education — where the child of a seamstress sits side by side with the son of a minister, in front of the same blackboard, receiving the same class from the same teacher. Something that’s hard to find in private schools.

This must be a law, a slogan, written with fire in the soul and conscience of all Cubans today. Regarding schools, like for almost everything else, it’s never been better said than by José Martí, who wrote: Either we save ourselves together, or we all sink.