Miami-Dade mayor sticks it to county workers

MIAMI – Recently, the war on worker’s rights and living standards that has been going on in this country for more than three decades has escalated significantly as bosses in the public sector have begun taking a page from their private sector counterparts. They are demanding a range of givebacks that essentially amount to two things: less money and less power for the average worker. Miami-Dade County is now one of the nation’s hot spots in this ongoing conflict.

The precedent for this latest twist in the top-down class war goes all the way to the early 1980s when Ronald Reagan broke the air traffic controllers union (PATCO) –ironically one of the few unions that had endorsed Reagan — by firing the traffic controllers en masse.

In retrospect, Reagan’s signal, which was initially picked up and acted upon most enthusiastically by business, was a major milestone in the drastic decline in labor union membership. Labor’s troubles in turn contributed to the erosion in the middle class living conditions that a large sector of the U.S. working class had increasingly come to enjoy and expect.

In the wake of Reagan’s successful confrontation with labor, corporations began breaking the decade’s-old implicit understanding between management and labor by challenging the legitimacy of unions and the notion that workers are entitled to a piece of a growing economic pie. An entire industry of consultants devoted to decertifying existing unions and preventing non-union workers from organizing mushroomed.

To be sure, the crisis of the labor movement and the shrinking of the middle class have resulted from several factors, including increased international competition as Germany and Japan arose from the ashes and as big new economic actors, such as China and India, became low-cost labor magnets for U.S. corporations empowered by the brave new world of globalization and selective free trade.

But the systematic hostility toward labor and the overt favoritism toward business and the rich embodied in the public policies and attitudes of successive Republican administrations — policies that Democratic presidents have been either uninterested or unable to roll back — have played a huge role too.

Republican presidents hostile to worker’s rights appointed judges in their own image, from the Supreme Court on down, with predictable results. By and large, members of Congress, more than 50 percent of whom are millionaires, and who rely on business and the rich to fund their political campaigns, by and large have failed to not provide the checks and balances to counteract the biases of the executive and judicial branches.

The fight against public employees, which raged in Wisconsin and others states last year, has now been joined big time in Miami-Dade. The background: Four years ago, amid the national financial implosion, county labor unions agreed to temporarily give up 5 percent of their base pay as a contribution to their health insurance. The giveback was to expire at the beginning of 2014. And, indeed, the Miami-Dade County Commission duly voted 8-5 to restore full pay to county and public hospital employees.

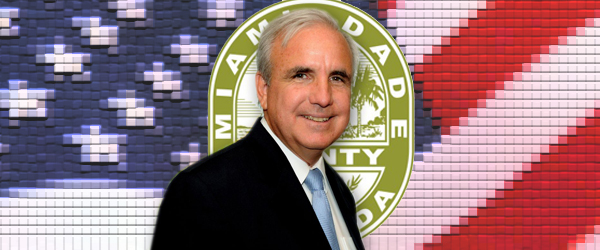

But Mayor Carlos Gimenez vetoed that decision. Under the strong mayor system adopted by voters several years ago, it takes the vote of two-thirds of the commissioners present to override a mayor’s veto. Eight votes out of thirteen doesn’t cut it, so the fight between county government and eleven public unions continued. Last week the Commission voted again, with the same outcome. The Mayor is adamant he will veto this vote too. Apparently, for Gimenez, there is nothing more permanent than a temporary concession and promises to employees are made to be broken.

All this is all-too-typical of the way the fiscal crisis has been dealt with in much of the country, namely on the backs of some of the people who can least afford its weight instead of by sharing the burden — and by breaking promises to workers.

But there is an interesting sidebar to this particular fight. Earlier, Gimenez had tried to pull the same stunt with the county’s sanitation workers. But only seven commissioners showed up, and the 5-2 majority in favor of full pay reached the two-thirds level needed to fend off a veto. The members of the commission are not supposed to discuss county business in private, but for some reason thirteen commissioners showed up for both votes on restoring pay to the rest of the county’s workers, including the five who enabled Gimenez’s veto by casting no votes. And two commissioners who earlier had said they would vote for pay restoration changed their minds at the last minute and cast two critical no votes.

Sometimes coincidences do happen. Somehow, I don’t think this is one of those times.