Building is a pain, in more ways than one

HAVANA — Any Cuban can tell hundreds of stories about the art of building. Some have had to build their homes from scratch and should be called blessed, because just having a place where to build a home is more than a privilege.

Others simply readjust the bedroom with the portion of the living room they were able to claim, in order to find privacy.

In the days of my parents, most people put up wooden or cardboard screens and cooked in a benzene camp stove by the side of the bed, when more than four couples cohabited in the same house.

Today, the people divide, restructure and do everything imaginable to improve their living space. Some inherit the house of a grandfather or uncle. Others made enough money in an international mission to buy a roof over their heads. Others spend their lives buying materials with money they receive from relatives abroad. Others do whatever they need to do; I knew of one who moved into the home of an unknown and lonely old man to take care of him until his death, so he could keep the house.

There’s a thousand ways to find the space, but no one can avoid the need to — at the very least — recover a wall, replace a door or break a floor because underneath there’s a broken pipe.

In a parody of the motto of the Cuban Ministry of Construction — “To engage in revolution is to build” — I like to say that to build is a real revolution. When you are ready to build, because you’ve obtained the privilege of space, you have to ask for a three-month unpaid sabbatical because you know that you cannot leave the masons alone in your house. Even when you’re present, they do a shoddy job and steal the materials; imagine what they’d do in your absence.

Gathering the necessary materials could well take you three months, because some of them are always unavailable. Why? Because some people hoard the materials so they can resell them at higher, unaffordable prices.

According to the ONEI (National Office of Statistics and Information), the average monthly salary rose from 466 Cuban pesos (CUP) in 2012 to 687 pesos in 2015; the equivalent in convertible pesos (CUC) is 27.48 CUC, or 27.48 U.S. dollars.

[Translator’s Note: Because of Cuba’s dual currency, one convertible peso (one dollar) is worth 25 Cuban pesos.]

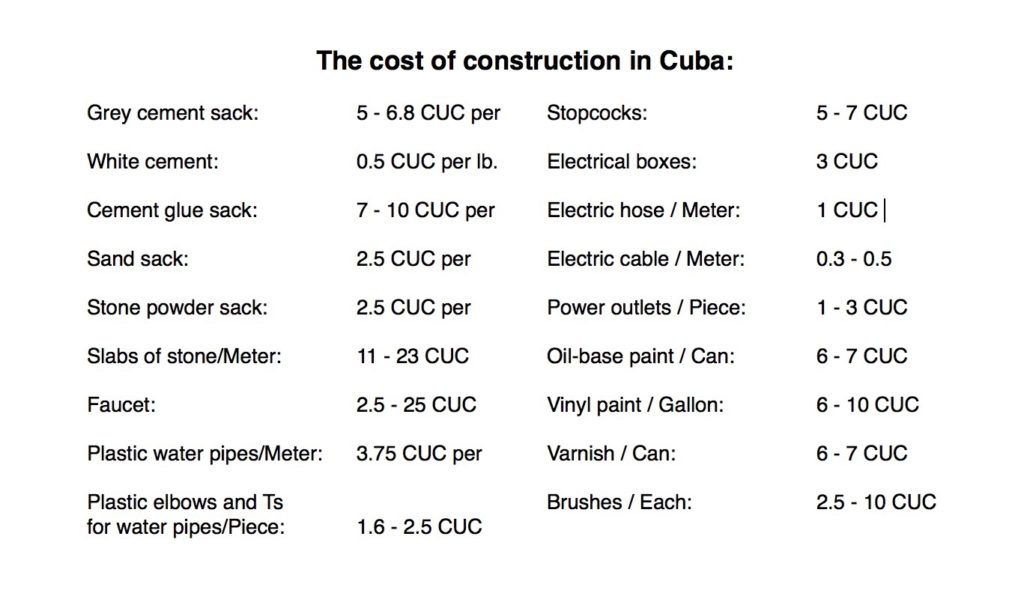

And what can one buy with 27.48 CUC when a pound of pork chops costs 1.60 CUC, a pound of tomatoes (two medium-size tomatoes) costs 1 CUC — and I don’t want to go on with the list, because we’d have to stop calling construction a financial burden. But I can tell you about some essential prices:

Now, suppose that, through Cuban magic, you have all the money you need and found a source for all the dry materials, and a truck that will bring them to you (at a time when nobody is looking), and a mason.

Then you’re ready to suffer the upheaval, your children’s and your allergy to dust, the need to use washbowls to do your laundry while the sink is replaced, the need to use a bucket while the toilet is fixed, the need to clean the floors daily and into the night, knowing that everything will be just as dirty the following day. Your hands will become dry and your cervical and lumbar vertebrae will screech with pain because either you’re a man helping the mason to move beds, boards and tools or you’re a woman doing the same.

Along with that comes the need to cope. To cope with the mason’s invoices (“and this is a special price for you”) which will keep you doing magic and infuriating you. Stories abound that legitimize the Cuban mason as a lazy cheater who leaves you in the lurch because he “had to take my son to the doctor’s” whereas he was doing a job that paid him more than yours. Worse, he did so after you paid in advance for his services.

If not, ask yourself why the French builders Bouygues hired more than 100 Indian workers to build the Manzana Hotel at the Manzana de Gómez building in the middle of Old Havana.

We must admit that Cuban manual labor is not sufficiently qualified for this type of work. Remember that masonry was a guild job and that masons had to earn their skills, beginning as apprentices. But that was before the 19th Century.

The Cuban construction workers I met in the 20th Century, and even this far in the 21st, learned to do careful work, to build forms for bricks, to install electricity, even plumbing. Yet, you see unskilled, unschooled workers offering their services because “you have to make a living” from something — or someone.

You must wonder how far can you trust a worker’s competence more than his personal ethics. There may be workers who are knowledgeable, skilled, neat, honest, but neither I nor all the people I’ve talked to have ever met someone with all these virtues combined.

On the other hand, where in this country can one find a place where such services may be hired? A place that legally defines timetables and wages? It seems almost funny to see unfinished state-run projects where the sun, the rain and time have erased from the signs the date when the project was supposed to have been inaugurated.

Or to see projects rushed into construction for the July 26 or January 1 celebrations, where the walls sag, or the paint peels off, or the floors are uneven, or etc. ad nauseam.

Nor do I trust the benefits of the private sector. Too many times have I eaten a good meal at a recently inaugurated restaurant, only to see the quality drop in a brief period of time. The rations become smaller, the food arrives undercooked.

However, like Martí, I hope for human improvement and long for the day when guilds become affordable and viable cooperatives. I dream of a carpenter who doesn’t steal my lumber and doesn’t take three or four months longer than agreed to install the windows I ordered. I hope that the proportion of cement to sand is really the one established in manuals and through experience, to prevent the cracking of walls and even disastrous accidents.

All this may seem laughable but is painful. We all like to dream and are eager to paint the walls ourselves, but deep inside us is the need to make of our space a worthy home, without so much hassle, without the habitual stresses we’ve experienced during those other revolutions we have managed to endure.

Photo at top of Cuban construction workers by Jorge Luis Baños.