Cuba’s harvest of surprises

In the fall of 1989, a full quarter-century before President Obama normalized US relations with Cuba, the Berlin Wall came tumbling to the ground in a flurry of sledgehammers and concrete dust. Meanwhile, an economic tsunami was brewing on the small Caribbean island. The Soviet Bloc was crumbling fast, sending shock waves across the globe that would plunge Cuba’s food and farming into years of austerity, hunger, and radical overhaul.

Earlier that year, the international socialist market terminated Cuba’s favorable trade rates—abruptly curtailing 85 percent of the tiny nation’s trade. Imports of wheat and other grains dropped by more than half; food rationing set in, and hunger widened. Soviet aid, a pillar of Cuba’s economy, evaporated as U.S. economic sanctions tightened.

Economic collapse led swiftly to agricultural crisis. Cuba’s industrialized farming system, fueled, literally, by Soviet tractors and petrochemicals, ground to a halt. Oil imports fell by 53 percent, and the supply of pesticides and fertilizers fell by 80 percent. Launching an era of austerity and reform known as the “Special Period in Time of Peace,” the Castro government “instituted drastic measures such as planned blackouts, the use of bicycles for mass transportation, and the use of animals in the place of tractors” to meet the unfolding crisis, according to a report by Food First, a U.S.-based think tank focused on food justice issues.

Cuba took a step back in time, transforming itself from an industrial farming machine into a traditional agrarian society. Soviet tractors, once ubiquitous on Cuba’s farmlands, were replaced by animal traction—oxen, horses, and cows. In just the first year of this change, the nation put 280,888 domesticated animals to work, according to a detailed study of Cuba’s agricultural transformation called “Agroecology Revolution,” referring to an agricultural science developed in Latin America.

Out of sheer necessity, an entire nation went largely local and organic. By 1990, Cuba began breaking up its big state-run farms. Much like its American counterparts, these industrial operations produced monoculture harvests, which were accomplished primarily with heavy machinery and fossil fuels. Now the government was issuing land use-rights, seeds, and marketing incentives to peasant farmers by the thousands. Over the next decade, according to “Agroecology Revolution,” Cuba’s farmers shifted to organic fertilizers, traditional crops and animal breeds, diversified farming with crop rotations, and non-toxic pest controls emphasizing the use of beneficial plants and insects. This blend of measures is part of a sustainable-agriculture approach known as agroecology. It’s often described as a promising innovation—which is a little ironic given that it draws on age-old peasant farming practices.

And in this case, the revolution was not born out of idealism. It was simply the only option on hand for a nation with no money to keep buying tractors, oil, and petrochemicals. “Necessity gave birth to a new consciousness,” explains Orlando Lugo Fonte, president of Cuba’s National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP).

Agroecology’s Big Harvest

Cuba’s agricultural de-tox represents “the largest conversion from conventional agriculture to organic and semi-organic farming that the world has ever known,” according to Food First. Across the countryside, a “campesino-a-campesino” (farmer-to-farmer) movement, growing more than 100,000 strong, shared techniques to stimulate production. Among the farmers’ guiding principles: “start slow, and start small;” “limit the introduction of technologies;” and “develop a multiplier effect” of farmer knowledge.

Great concepts, but what about results on the ground? By 2007, ANAP found, Cuba had stabilized and in some areas expanded food production even as farmers dramatically reduced pesticide use. While scaling back pesticides anywhere from 55-85 percent across a range of crops, peasant farmers produced 85 percent more tubers, 83 percent more vegetables, and 351 percent more beans.

Cuba’s farming revolution propelled the island from the lowest per capita food producer in Latin America and the Caribbean to its most prolific, says Miguel Altieri, UC Berkeley professor of agroecology. Writing in The Monthly Review, Altieri and Fernando Funes-Monzote, a founding member of the Cuban Organic Agriculture Movement, came to a dramatic conclusion: “No other country in the world has achieved this level of success with a form of agriculture that uses the ecological services of biodiversity and reduces food miles, energy use, and effectively closes local production and consumption cycles.”

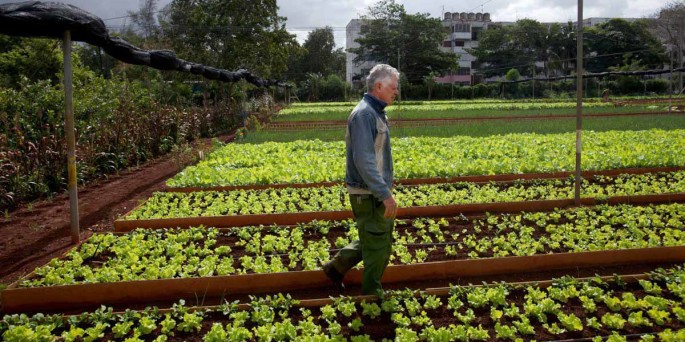

Perhaps most notable is Cuba’s explosion in urban agriculture. After the Soviet collapse, the Castro government distributed 13-hectare plots of farmland to young farmers within a 10-mile radius of urban centers, to ensure that people in the cities could eat. Within city limits, Altieri and Funes-Monzote reported in 2012, urban farms supply 70 percent or more of all the fresh vegetables consumed in Havana and Villa Clara, two of Cuba’s most densely populated centers. Nationwide, some 383,000 urban farms produce more than 1.5 million tons of vegetables.

Cuba’s food revolution is by no means a complete success, and there is cause for concern about its future. Cuba still imports a hefty portion of its food, though the precise amount is roundly debated. At a January 8 event unveiling a new “US Agriculture Coalition for Cuba”—which includes commodity groups such as the American Soybean Association and the National Association of Wheat Growers—US Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack stated, “Cuba imports about 80 percent of its food, which means that the economic potential for our producers is significant.” The USDA says it obtained this figure from the UN World Food Programme, but according to other research, including a 2012 Food First book, “Unfinished Puzzle,” Cuba imports roughly half of its food supply. Cuba has spent more money on food imports since then, but the book says that much of that increase is due to rising food and oil prices.

Why might Secretary Vilsack favor one number and not another? “US farmers and agribusiness have long been interested in gaining access to Cuban markets,” says Tanya Kerssen, research coordinator for Food First. If that brings a fresh influx of imports, she says, “Cuba may not have the opportunity to fix problems in its food system because it might get railroaded by a flood of industrial food and synthetic farm inputs [pesticides and chemical fertilizers].” Kerssen fears that a change of this scale could “overwhelm Cuba’s system”—with a form of agriculture, ironically enough, that is not so different from the one it shed in 1989. “If this happens,” Kerssen says, “we may never get to see all the results of the agroecology revolution.”

Still, to Peter Rosset, a professor at the ECOSUR Advanced Studies Institute in Chiapas, Mexico, and a staff member for La Via Campesina, a global peasant farmer movement, the Cuba story proves that agroecology “is the way to produce as much food as we need.” Rosset, who co-authored “Agroecology Revolution,” says the farming approaches he studied in Cuba “can lower costs for farm families and provide them with a better life, and in ways that are more resilient to climate shocks.”

Beyond Cuba, researchers are finding that agroecology can produce harvests on par with industrial agriculture, while doing so more sustainably. Analyzing data from 115 different crop studies, a team of UC Berkeley environmental scientists concluded that age-old techniques such as multi-cropping and rotations—which, respectively, intermingle various crops in a single row for greater productivity, and rotate crops to nourish and replenish soils—“substantially reduce” any gap between organic and “conventional” agriculture. They concluded that investment in agroecological research “could greatly reduce or eliminate the yield gap for some crops or regions.”

Could it happen here?

Flanked by a lush, dark-green eruption of chard and fava beans at a tiny eighth-of-an-acre garden plot in Berkeley, Altieri scribbles numbers on a notepad, producing some compelling calculations: Applying agroecology methods on1200 acres of public lands, the city of Oakland could produce 25,000 tons of food annually—enough to feed at least 400,000 people—without any pesticides or genetically engineered “super plants.” Such a change would be huge, Altieri argues, since the Bay Area imports 6,000 tons of food each day, which lean heavily on fossil fuel. But for a host of reasons, it’s not likely, he says.

Despite agroecology’s impressive harvests in Cuba, Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, and other parts of Latin America, Altieri doesn’t see it taking root here. “I don’t think there is an agroecology movement in the US. Agroecology is a science developed in Latin America, connected to social movements like La Via Campesina,” says Altieri. Those movements are virtually absent here. Even in Berkeley, land of foodies and sustainable-ag acolytes, “they take the ecological principles, but strip it of its true social importance,” Altieri says. That social context, in Altieri’s view, has as much to do with democratizing food systems as with farming techniques. “We can learn the techniques, but these are socio-ecological systems, not just ecological systems.”

Altieri says two big changes are needed first: access to land (particularly for younger farmers), and public investment in small-scale sustainable farming. In the U.S., the bulk of US farm subsidies benefit large-scale industrial farms; in Brazil, by comparison, national agricultural law requires the government to purchase 30 percent of small farms’ harvests, Altieri explains. “Can you imagine if that happened here? Those laws happened because social movements brought pressure.”

Despite the obstacles, ecological urban farming is spreading, albeit on a small scale. New policies in Oakland and in San Francisco have given gardeners easier access to land and water, under a “Right to Grow” concept. “When we can grow food for ourselves,” says Esperanza Pallana, executive director of the Oakland Food Policy Council, “that is independence.”

Even if agroecology is relegated to small advances in the U.S., Altieri believes it can still heal. “When people go back to the land and transorm [it] through agroecology, they transform themselves—they become better people, better parents, better husbands.” And the land, he says, takes notice: “Treat nature with respect and dignity, and nature responds.”

Beyond inspiration, Cuba’s organic revolution also offers a warning. “We have two paradigms that are clashing,” says Altieri, “the industrial model and the ecological one. Humanity has to make up its mind which way we want to go. The question for the US is, do we wait for the agricultural system to collapse before we make a change?”

Christopher D. Cook has written for Harper’s, the Los Angeles Times, Mother Jones, The Christian Science Monitor and elsewhere. He is the author of Diet for a Dead Planet: Big Business and the Coming Food Crisis.

(From: Craftmanship)