Marco Rubio’s house of horrors

The brick-fronted tract house with a satellite dish and a yellow fire hydrant in front looks like many middle-class homes in Florida’s capital, except for the two names on the deed.

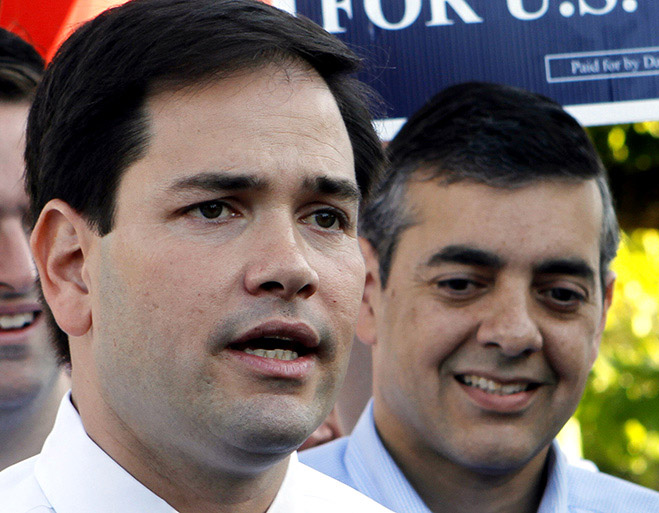

Marco Rubio: U.S. senator and would-be presidential candidate.

David Rivera: Scandal-plagued former congressman under investigation in a federal campaign-finance probe.

In many ways, it has been a house of horrors for Rubio, a financial and political liability heading into the 2016 election. While he and Rivera were state legislators, they paid way too much for it in 2005, only to see foreclosure proceedings embarrassingly initiated against them during Rubio’s 2010 Senate race. At another point, a tropical storm flooded the entire neighborhood so badly that neighbors used canoes to get around.

Now, the three-bedroom property stands as a stubborn symbol of both a politically problematic friendship and lingering questions about Rubio’s personal finances, which dogged him on the campaign trail in 2010 and may do so again. The friendship has frayed in recent years, friends say, as the fortunes of Rubio, 43, and Rivera, 49, have diverged. Last week, they put the 1,228-square-foot house up for sale. The list price is $125,000 — $10,000 less than what the two men paid for it a decade ago.

But chances are the home won’t sell before April, when Rubio says he’ll decide whether to seek the presidency. Rubio’s critics are waiting to make hay of any revelations that may come of the federal investigation of Rivera and to point to their status as roommates during the years when Rivera allegedly engaged in illegal campaign activities.

“This will be an issue,” declared Craig Smith, a top adviser for the Ready for Hillary super PAC, echoing the views of many supporters and detractors alike. “When you run for president, voters and the press have an insatiable appetite for people’s histories, what they’ve done, who they are. … It raises questions about his judgment, about the kind of people he would bring with him into government, into a campaign.”

Rubio declined to comment for this story or about his relationship with Rivera, with whom he bought the Tallahassee home for lodging when the two up-and-coming legislators served together in the Florida House. A Rubio spokesman and Rivera both denied that the sale of the house had any political motivations. The home’s tenant since 2010 recently moved out, and they’ve been trying to sell the house, unsuccessfully, for years.

Asked about the status of Rubio’s relationship with Rivera, which dates to 1992, when both men worked for the congressional campaign of Lincoln Diaz-Balart, spokesman Alex Burgos said in a written statement: “David Rivera is an old friend of Senator Rubio’s. His hope is that Mr. Rivera can put his recent troubles behind him and go on with his life.”

But interviews with more than a dozen friends and political insiders who have known the two for years suggest that the story is more complicated, and that Rubio is stuck between his sense of loyalty to his friend and his need to move on with his life and political career. Three people close to Rubio say he has referred to Rivera on multiple occasions as “Nixonian.”

And yet others describe a brotherly closeness that became strained only as Rivera weathered state and federal investigations into his finances, a related state ethics case that recently resulted in a proposed $58,000 fine, and the more serious campaign-finance scandal that erupted in 2012. At the time, Rubio and Rivera shared a rental home in Washington for the two years they both served in Congress.

“Marco wants little to do with David, and you can’t blame him — who would want that guy by their side as they’re running for president?” said Ana Alliegro, Rivera’s former girlfriend, who pleaded guilty last year to campaign-finance violations and making false statements in the most recent federal case involving Rivera. She recently gave grand-jury testimony against Rivera.

Alliegro confirmed she told prosecutors that Rivera was the source of about $81,000 in unreported cash that was used to fund the 2012 campaign of a political unknown who was running in the Democratic primary against Joe Garcia, a formidable contender preparing to square off against the Republican Rivera in the general election. Garcia prevailed against the candidate to whom Rivera allegedly funneled the money, Justin Sternad, who later pleaded guilty to federal charges of breaking campaign finance laws and filing false campaign reports.

That November, Garcia beat Rivera. Days before the election, Rubio recorded a robocall touting Rivera. Rubio also, however, made similar calls for other Republican candidates.

In open court and at the urging of a judge, a federal prosecutor has twice labeled Rivera as an alleged criminal conspirator in the case. But Rivera doesn’t just deny wrongdoing — he claims he’s not the subject of a probe.

“As I’ve said repeatedly, no federal agency has ever said I am under investigation and no ‘former girlfriend’ has ever testified against me. That would be impossible since I have never been a defendant to be testified against,” Rivera said via email. “Please send me this alleged ‘announcement’ by the federal government that I’m under federal investigation and please identify the agency that announced it,” he wrote. “Neither exist.”

Rivera also disputed the notion that his relationship with Rubio has changed. He said the two spoke “recently” by phone.

If the two still talk, it doesn’t surprise former state Rep. J.C. Planas, a Miami Republican who served with the two in the state House. Planas said Rubio was loyal to a fault and that it could prove costly in 2016.

“David Rivera reminds me of the villain Iago in ‘Othello’ — and Marco’s political career is Desdemona,” Planas said. “Marco has stood by David, and it’s just baffling to me. I’ve never understood their relationship.”

Rubio owes a measure of his early success in politics to Rivera. Rivera advised and stumped for Rubio in his first campaign for the state House in 2000. Once elected, Rubio repaid the favor and helped Rivera win a state House seat in 2002. The following year, Rivera was instrumental in helping Rubio collect pledge cards from fellow Republicans to eventually become the first Cuban-American speaker of the Florida House. A relentless political operative, Rivera popped up in seemingly every corner of the state throughout the year to pressure, cajole and win over GOP House members to support Rubio for speaker.

As the two climbed the rungs of power together in the Florida House, they decided to buy the home at 1484 Bent Willow Drive in the Timber Lakes subdivision for $135,000. The March 2, 2005, deed was executed about a week before the 60-day lawmaking session began that year. When Rubio was formally voted speaker, he was nominated by Rivera, who served as chairman of the Florida House Rules Committee during Rubio’s speakership in 2007 and 2008. The post gave Rivera life-and-death power over much of the legislation in the House.

Affable, intense and intelligent, Rivera was often a source of mystery to his colleagues in the part-time Florida Legislature. Year after year, his financial disclosure forms claimed income from the U.S. Agency for International Development. But years later, The Miami Herald reported that USAID had no record that he ever worked with the agency.

Asked what the former lawmaker was up to these days, a close ally of both men summed up the prevailing sentiment about Rivera: “I don’t know. And I don’t ask. I don’t want to know.”

“I always thought he worked for the CIA,” said Miami-Dade County Commissioner Esteban “Steve” Bovo, who served with Rivera and Rubio in the House and whose wife, Viviana, is a Rubio aide.

In Rivera’s ethics case, investigators with the Florida Commission on Ethics and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement testified before an administrative law judge at a hearing that records showed Rivera was essentially living off political committee funds and failing to disclose the money as income. Rivera also arranged a contract worth $1 million between a Miami dog track and a company owned by his mother to lead a 2008 election campaign to legalize slot machine gambling in Miami-Dade County. Rivera later acknowledged accepting at least $132,000 as part of the arrangement. But he didn’t list the money on his state financial disclosure forms.

At the time, Rivera told reporters he wasn’t making “a penny” off the gambling referendum. And as Rivera was getting money from the company that became Magic City Casino in 2008, Rubio opposed expanding gambling while serving as House speaker.

Later, after the casino deal came to light, Rivera claimed in his ethics case defense that the gambling money was a “contingent liability loan” that wasn’t reportable “income.” The Internal Revenue Service, which examined the payments and his finances along with the FBI, opted not to charge him after interviewing a handful of witnesses.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement also examined his finances and drafted a 52-count complaint. But the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office decided in late 2011 not to charge Rivera because of ambiguities in the state’s ethics laws and, in some matters, the statute of limitations.

Throughout the investigations, Rivera denied to reporters that he was the subject of the probes — even while a defense lawyer was negotiating with investigators on his behalf.

A Florida judge in the civil ethics case concerning Rivera’s finances determined that he “corruptly” failed to disclose his income and double-billed taxpayers for travel paid by a political committee associated with him. On March 5, the judge recommended a nearly $58,000 fine against Rivera. The ethics commission will take up the case April 17, just as Rubio might be running for president.

Like Rivera, Rubio also double-billed taxpayers for flights paid for by a political group, in his case the Republican Party of Florida. When the matter was brought to Rubio’s attention during his 2010 Senate race, Rubio told The Miami Herald and St. Petersburg Times that it was an error, and he agreed to pay back the party $2,400. During the 2010 campaign, Rubio’s state GOP-issued American Express bills from 2005-08 were obtained by the Herald.

In all, Rubio racked up about $100,000 in charges for meals and travel as well as a few groceries, a family minivan repair, a salon expense and even a family vacation in Georgia. Rubio said at the time that most of the charges were for party-building reasons and that any personal charges rung up on the cards — such as the Georgia trip — were paid directly to the credit-card company by him.

In some cases, Rubio said, his travel agent made an error by using the wrong card. Other times, he acknowledged he did the same thing, as at a home-improvement store.

“For example, I pulled the wrong card from my wallet to pay for pavers,” he disclosed for the first time two years ago in his autobiography, “American Son.” In the book, Rubio dismisses most of the criticisms against him and his spending as motivated by politics or the news media’s thirst for scandal. Still, Rubio did acknowledge in his book that it was a book-keeping “disaster” for him and his wife to manage two political committees that raised about $600,000 to help his bid for speaker.

The IRS examined the finances of Rubio and other GOP politicians and in late 2010 slapped a subpoena for financial records on the Republican Party of Florida. But the probe ended without any charges or any other publicly observable activity.

The credit-card and political-committee spending weren’t the only paperwork nightmares for Rubio.

After he became speaker, the Herald discovered in 2008 that he took out a $135,000 home-equity line of credit on his West Miami house but failed to report it on his financial disclosures. The lender, Miami-based U.S. Century Bank, gave him the loan just 37 days after Rubio bought the house.

“There’s nothing unusual about the loan or the application,” Rubio told the Herald at the time. “They went out and ordered the appraisal. … They said I qualified for $135,000. I took the equity line.”

Rubio explained that the failure to disclose the loan was “an oversight,” and he amended his forms.

Two years later, a worse housing problem — this time in Tallahassee — vexed him.

In June 2010, Deutsche Bank hired a company to initiate foreclosure proceedings on the house he co-owned with Rivera, claiming the mortgage had not been paid for five months. During that period, Rivera had been in Tallahassee for pre-session committee weeks and the regular 60-day lawmaking session that begins in March. The two men characterized the dispute as a disagreement with the bank over the interest-only mortgage they had on the property.

News of the foreclosure rocked Rubio on the campaign trail. Rivera, running for his first and only successful congressional bid, quickly hand-delivered a $9,525 cashier’s check to cover missed payments and fees.

“There is no foreclosure,” Rivera told the St. Petersburg Times then. “The mortgage is paid and up to date.”

Rubio was infuriated, friends say. Rubio has handled paying the mortgage ever since. He and Rivera got a mutual friend to help manage the property and find a tenant later that year, a single mother who recently moved out. The tenant declined to speak with POLITICO, but she said in a written statement that Rubio and his wife “have been very gracious and understanding of my circumstances.” She called them “extraordinary landlords” and expressed her “deep appreciation … for all that you’ve done.”

Neighbors say they had little idea about the drama surrounding the house or the ambitions of Rubio. Caridad Tamayo, who has lived in the neighborhood for five years, said she didn’t recognize Rubio’s name. Neighbor Richard Linck said he knew about Rubio but had “no idea” he was planning to run for president.

“The reality is Marco wants to sell this house because it’s horrible,” one friend said. “It’s been nothing but trouble for him. There was the foreclosure. There was a flood that made it tough to get to without a canoe at one point. And there’s David. Marco won’t turn his back on David. But we all wish he would.”

Rubio has kept his distance more and more from Rivera as Rubio became a serious, national figure while Rivera lost his congressional seat and reeled from multiple scandals.

Rubio, his friends and allies say, knows he’s going to be questioned repeatedly about the house, Rivera and his finances. And, they predict, it ultimately won’t make a difference to voters nationwide, just as it didn’t cost him his shot at the U.S. Senate in 2010.

In 2012, however, many political insiders buzzed that Rubio wasn’t picked to become the vice-presidential running mate for Mitt Romney because of past questions about his finances and his associations with Rivera.

But Romney’s campaign manager, Matt Rhoades, said the gossip about Rubio failing in the vetting process isn’t true. “Marco Rubio was thoroughly vetted for vice president. Our team was confident that, if chosen, his legislative record and high personal character would have been a great asset to Mitt on the campaign trail and in office,” Rhoades told POLITICO last week via email.

“I asked the vetting team if there was anything in Marco’s past that would disqualify him as [a] vice presidential candidate and they said there was not,” he said. “Marco was one of the most effective and hard working surrogates the Romney campaign had and I’m certain that will translate as a presidential candidate should he decide to run.”

(From: Politico)