Arguing at the Versailles

MIAMI — On Dec. 17, a bridge was built over more than 50 years of political tension between Cuba and the United States. The simultaneous release of American subcontractor Alan Gross and three Cubans — Gerardo Hernández, Ramón Labañino and Antonio Guerrero — as well as the surprise announcement that the U.S. and Cuba would act to reestablish diplomatic relations generated a climate of euphoria among Cubans on the island and abroad.

In Miami, at the emblematic Versailles Restaurant on Southwest Eighth Street, a historic stage for demonstrations by Cubans who oppose the governments of Fidel and Raúl Castro, the situation was different this Wednesday. Hundreds of people stayed until late into the night arguing about the speeches by Barack Obama and Raúl Castro.

And we say “arguing” because this was an unusual protest at the Versailles, a clear demonstration that the ideological stances of Miami’s Cuban community have been changing in the past 10 years.

It wasn’t, as usual, a group that opposed the Castro brothers. To the Versailles this Wednesday came people who wanted to make public their support for the new measures.

Three moods prevailed among the crowd. One, the disillusionment and dejection of those who believe that any effort to move closer to the island is nothing but a concession to the Castros.

“The reestablishment of diplomatic relations with Cuba is absurd,” said the chairman of the Cuban Democratic Directorate, Orlando Gutiérrez. “It means a concession to a government that continues to oppress the Cuban people and exerts a corrosive influence on the democracies of Latin America.”

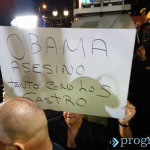

Opinions like that were shouted outside the restaurant, where a feeling of indignation reigned. Indignation not only against Obama and Raúl but also against another group of Cubans who stood firm, expressing to one and all their agreement with the reestablishment of diplomatic relations and the end of the embargo.

“Communists!” yelled the former, “Miami is filling up with communists!” Was that a fair accusation?

We approached a young man who defended his ideas with determination. He declined to tell us his name. He had chosen not to speak before the many cameras outside the restaurant. However, he walked away a bit and explained to us why he was there from an early hour and would remain there until everyone else had left.

“I don’t believe in politics or politicians,” he told us. “I came to this country because my family so decided and have fallen in love with Miami. But that doesn’t exclude my love for Cuba, my happy years. My family came here 15 years ago because we won the [visa] lottery. We applied for the lottery because we wanted to try our luck outside Cuba, because in Cuba we had little chance of finding a home.

“Throughout those 15 years I’ve changed a lot. I’ve grown at the pace someone grows in a foreign country, which is almost always a tough growth based on sacrifice, dreams and constant rebirth.

“I’ve gone to Cuba every chance I’ve had, and that means many times. In recent months, I’ve seen a Cuba on the move, a Cuba that seems to have everything it needs to prosper, and it hurts me — it hurts me a lot — that all those people are turning their rancor into a banner against common sense.

“In Miami I have learned to understand the pain of many people who arrived in this country under circumstances different from mine. People who, throughout these 50 years, have arrived here telling a story that explains their opposition to the Cuban government. I have learned to respect and understand them, but I know very well that that’s not my story.

“Coming to Miami cannot be a synonym for breaking relations with Cuba. I believe that the blockade is really an absurdity, that people and nations should have the right to get ahead, that you can’t go to the university if your parents keep you from taking the admission tests, that the time has come — it came years ago — to look forward, despite the rancor.

“I believe that Cuba deserves, like any other country, to have that opportunity and that it is — I repeat — a unique absurdity for someone to object to the reestablishment of diplomatic relations between two nations.

“I’ve repeatedly asked for those alleged reasons here, but — other than hearing stories of people’s personal lives and being accused of being a communist — nobody has yet to tell me what sense the embargo makes.”

We could have spent the whole night dialoguing, but someone interrupted us. At the end of the night, we met one of those many people who were at the Versailles as spectators, wishing to know how each side felt.

She had arrived in the U.S. five months ago and only one concern weighed on her mind.

“If they change the laws before I become a resident, can I still be one?” she asked.

“We don’t know,” we answered. “Does that scare you?”

“A lot,” she replied. “The uncertainty has not allowed me to celebrate.”

And that was clearly the third group, the group of those who say nothing but worry about their personal fate. They don’t support either side but if you ask them three times they end up saying that they wish for peace.

The nation is constituted by all of us, here and there, and is not unanimous. Some think that the opening is counterproductive, that it would encourage a climate of restriction and authoritarianism. Others suppose that it is the start of the relaxation needed to abandon a scheme of confrontation and defense, so that the current economic openings may be accompanied by more participative political reforms.

At the core, there is truth in all this. Today, we all speak; those who congratulated Obama for a history-making decision; those who accuse him of treason; those who fear the possibility that, before one year and one day, the Cuban Adjustment Act might be revoked; those who want to return; those who don’t look back.

Cuba spoke in Miami and the Versailles with a multiplicity of languages that are only a sample of how much the country and the community of Cuban émigrés have changed. What sense would a paralyzed diplomatic policy make?