Destination Miami

More than 2,500 Cubans arrived at the Canadian border during fiscal year 2013. The figure does not discriminate between those who, like me, asked for asylum and those who didn’t.

*****

Sandra slips a Lana del Rey disc into the car’s CD player. It’s May 16. Sunday. My stomach is empty, queasy. Sandra’s boyfriend is driving; his name is Armando.

From the back seat, I notice that Armando’s hands are calloused, although the calluses are rather small, as if an allergy had affected the skin of his hands. I get the feeling that Armando works a lot but that he started working only recently.

To save time, Sandra proposes eating breakfast at a Tim Hortons coffee shop without getting off the car, stopping at the drive-thru. Armando speaks no English; Sandra speaks it fluently. I guess that the outside temperature is minus-10 Celsius. I don’t know what to ask for; maybe a cappuccino and some cookies. I do know that I won’t eat anything.

The car takes a shortcut to a highway. I ask if that’s the highway to Niagara. No response. Leaving Toronto, I can see a lot of snow. I wonder: what if the snow, not Toronto, is the only city, the real capital of Ontario, a city without limits or summer school where it’s commonplace to see Mayor Rob Ford drinking, leaning on his sleigh?

I screw my head back on, at once. I think about my mother. Eventually I think about Heredia, the poet, about what he did to come here. It is not something explained in “The Novel of my Life,” I tell Sandra. Or is it? *

My queasiness has three sources: my stomach, the reason for traveling, the highway. I think that, after many years, something in me is just beginning to die. I lean back. I’m intrigued by a used-car dealership where I see gray Mazdas, improbable heaps.

A short distance away, with no birds in sight, I see a dry lake covered by snow. The fish must have been sold cheap, I think.

…

Sandra’s car stops outside a hotel. We hug. They go flag a taxi for me while I get the luggage. The temperature is below 5 Celsius. Armando returns, seems anxious. He grabs my shoulder and says, “Brother, remember, don’t tell anyone that we brought you here, is that clear?”

“Relax,” I say. “Sandri, a kiss?”

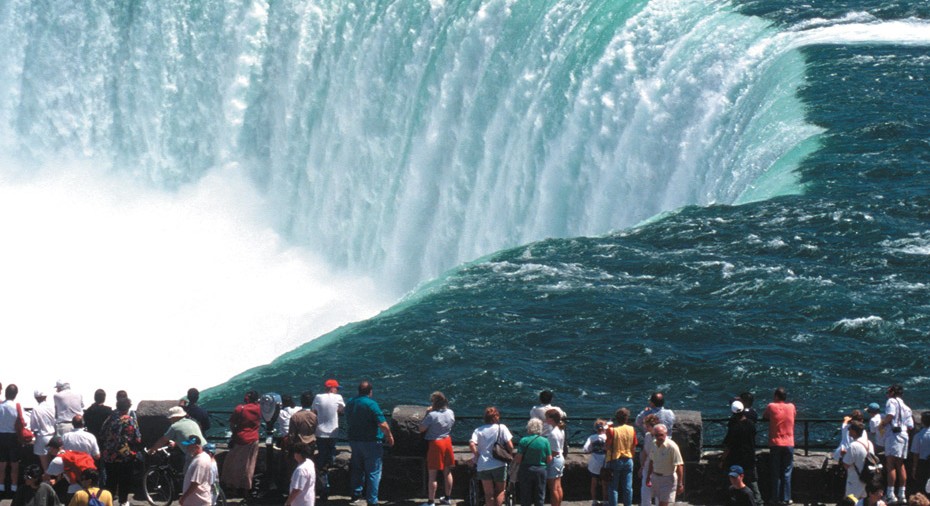

The taxi takes me to the checkpoint. I barely notice the falls. I know, however, that they’re overrated. At least in winter.

I owe the driver 35 dollars. All for a five-minute ride! For a distance that I could have covered — with a little more energy, without at least one of the two suitcases — on foot. A distance that in Havana I walked every day, from Carlos III, down Ayestarán, to the bus terminal. I screw my head back in place.

Two officers stand there. The one in the booth, the younger of the two, asks for my passport. He thumbs through it, bends it in every direction. He looks like some who’s been doing that for years. The other one walks over and asks that I step off the taxi. He puts his left hand on his head and asks why I left Cuba, why I’m asking for asylum.

Do you want the long story or the short one? I think.

“Because I wasn’t free over there,” I say.

The officer inside the booth tells me to go to a building some 40 yards away and wait to be interviewed. I sit down. The elevator had a surveillance camera, the air was stale. I hear my name and two surnames.

I go into a room, they ask me to sit down and fill some forms. Nonsensical stuff. An address, a mailing address. They don’t even ask for my telephone number. I hear my name and two surnames again. I stand up. An officer shows me a picture.

“Do you know him?” the man asks, pointing at the picture. He looks at his companion, a fat, liver-faced guy.

“Sure, it’s Pitbull,” I answer. “And he’s Cuban, right?”

“Yes, that’s why I’m asking.” The two smile weakly.

“And this one?”

“Jean-Claude van Damme.” I lift my eyes from the picture and fix them on the officer. “But he’s not Cuban.”

“Exactly. That’s why I’m asking.” The officer again looks at the fat man, with a complicity that begins to seem clumsy, unpleasant.

“What can you tell me about this one?” The fat man, who had been smirking all along, purses his lips, expectantly.

I pretend that I’m thinking, for about five seconds, and answer:

“Obama.”

“Oh, my God! you’re a fucking genius!”

Suddenly, the fat man takes a fourth picture out of the desk drawer. He takes his time. He signals a supervisor nearby, with unintelligible gestures that, to the supervisor, seem clear. At least, he doesn’t shrug or interrupts his interview with a man who, from a distance of about 6 yards, seems to be a Thai. An old Thai.

“Listen to me,” the fat man tells me. “I’m going to show you a fourth picture. No Cuban has ever told me who the character in the fourth picture is. Furthermore, no Cuban has ever gone past the second picture. If you can tell me the name of the character who I’m going to show you” (his voice acquires an absurd menacing tone) “I myself will take your fingerprints and record your statement.”

The fat man begins to display the fourth picture. This time, the other officer, elbows on his desk, leans forward expectantly. A young woman, who appears to be a clerical worker, serves coffee to others and shows no interest in what’s going on.

“Wait.” The situation is getting out of hand. “What if I can’t? What happens if I can’t identify the fourth character? No Miami?”

“Could be,” they say, laughing raucously.

“LeBron James,” I answer. “Anything else?”

[*Translator’s Note: Cuban poet José María Heredia wrote the poem “Ode to Niagara” in 1824, while a political exile. An English translation appears here.]