1,000 days: Julian Assange, Ecuador and the US war on truth

On Monday Julian Assange marks his 1,000th day in the Ecuadorean embassy in London. 24,000 hours spent trapped in a handful of little rooms in a non-descript Knightsbridge road: tirelessly working, rarely venturing into the sunlight.

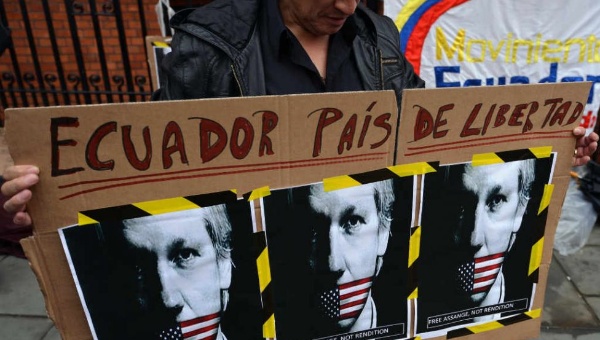

While the building appears unremarkable, the symbolism of the four walls is great. Because ironically, the inside represents the freedom offered by the Latin American country, and outside, persecution and indefinite imprisonment await. Yet the Australian national has never been charged with a crime.

This is the tale of one of the greatest battles over freedom of speech in modern history, and how the tiny nation of Ecuador became an internationally recognized champion of human rights against the opposition of two imperialist giants.

In interviews with teleSUR, Wikileaks founder Julian Assange and Ecuador’s Foreign minister have outlined the significance of this battle to defend those who publish the truth, whatever the consequences for the powerful.

Patino believes that these events underline how they show a “commitment to safeguarding human rights, freedom and life”, in today’s Latin America that is in stark contrast to a past riddled with dictators and human rights abused

“It has been a difficult 1000 days. Not so much for me but for my family,” Assange told teleSUR in an interview in the run up to the Monday’s anniversary.

“For me, I have plenty of things to concentrate on that are not in the embassy. I have an organization to run.”

That “organization,” Assange’s website Wikileaks, exploded into the limelight in April 2010 when it released an electrifying U.S. military video. It depicted U.S. military personnel in an Apache helicopter killing 18 civilians in the Iraqi suburb of New Baghdad, including two Reuters staff. The clip, entitled Collateral Murder, would be the first piece of evidence pointing to U.S. war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan in the public domain.

Two months later, Chelsea Manning, a then-22-year-old intelligence private with the U.S. military in Iraq, was arrested, charged with disclosing national secrets. It would later become apparent that Manning had executed the biggest leak in history: millions upon millions of top secret computer files, cascades of damaging documents.

Assange set about making partnerships with newspapers and television networks around the world to analyze and publish the information. According to Vanity Fair, the Wikileaks founder said, “I have a record of every single episode involving the U.S. military in Afghanistan for the last seven years … I have a record of every single episode involving the U.S. military in Iraq since March 2003.”

The cache of information changed the media landscape, and made Assange one of the most wanted men in the world.

Over the next months, Assange and his media partners carefully orchestrated the spill, landing blow after blow to the reputation of the U.S. military and government by publishing the real ways it works. The world came to understand the full extent of the abuses.

But then in December that year Assange was arrested for sexual assault, allegations stemming from when he had visited Sweden earlier that year. A warrant was issued for his extradition to Stockholm, and Assange spent a few months under house arrest in England. A London court approved the extradition in February 2011.

Fearing that if he were to go to Stockholm to face questions the Swedish government would pack him straight off the U.S. to be tried over the Wikileaks scandal, Assange sought refuge with Ecuador. The Australian had met President Rafael Correa while hosting a show for Russia Today, and the two had shared views on rights, justice and the corporate media , which in part propelled Assange to later seek asylum there.

Since then, and for the next 1,000 days, Assange has been unable to leave the Ecuadorean embassy in London. Police hover outside, poised to arrest him and send him on to Sweden, or worse, the United States. The British government has spent nearly US$15 million on guarding the building, while Assange and his lawyers have engaged in a battle clear his name.

As Patino explained to teleSUR, Ecuador has repeatedly “sought a solution from the outset,” for all the people involved in the Swedish case and one “that’s compatible with the norms and principles of international law.” Yet offers to the Swedish prosecutors to “interview Julian Assange at the Embassy of Ecuador, either in the presence of Swedish officials themselves or via videoconference” were rebuffed or even described as not legally possible.

After nearly 1000 days, a breakthrough on that front came earlier this week when Swedish prosecutors finally agreed to question Assange within the embassy. The move is seen as a boost to Assange’s attempt to prove his innocence. But even if the Swedish arrest warrant is dropped, it doesn’t mean Assange can walk from the embassy a free man.

“The UK has said that even if that happens they are going to arrest me anyway and you also have the U.S. case,” Assange told teleSUR.

A war on journalism

Assange’s fears over extradition to the U.S. are far from unfounded. His team already has proof that the U.S. is amassing a full-blown case to put him behind bars.

In 2012, Wikileaks revealed that a secret indictment had been brought against Assange by the U.S. A mysterious Secret Grand Jury, or the “neo-McCarthyist witch hunt against Wikileaks,” as Assange describes it , was gathering evidence.

“Not for Pub(lication) — We have a sealed indictment on Assange. Pls protect,” one leaked memo read.

“Assange is going to make a nice bride in prison. Screw the terrorist. He’ll be eating cat food forever,” said another.

According to secret documents leaked by former employee Edward Snowden, Assange had been placed on a National Security Agency manhunt list in 2010, while further information confirms that U.S. military intelligence was spying on him from 2009.

“Our publications beginning 2010 set off a major conflict with the U.S. government,” says Assange.

“As a result, the U.S. started up what it calls a whole government investigation, involving more than a dozen different U.S. agencies that is believed to be the largest ever investigation into a publisher.”

Google admitted it handed over all information that it had on three Wikileaks staff and journalists. Wikileaks said it was “astonished and disturbed” to find that Google had passed on the private emails, search terms and more, over two years ago.

“Not only did they place Google under gag orders, but the subpoenas revealed a sort of legal attack that the U.S. government is making on media and on WikiLeaks,” Assange explains. “…they are investigating – which add up to 45 years in prison – espionage, conspiracy to commit espionage, computer hacking, general conspiracy, theft of U.S. government information.”

The same acts, against the 1917 Espionage Act and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, were used to jail Manning, who irrevocably changed the game of whistleblowing.

Manning was sentenced to 35 years in prison and is currently being held in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. She was subjected to 11 months of solitary confinement before being tried, and according the United Nations, was humiliated and degraded.

“The special rapporteur concludes that imposing seriously punitive conditions of detention on someone who has not been found guilty of any crime is a violation of (her) right to physical and psychological integrity as well as of his presumption of innocence,” U.N. special rapporteur on torture Juan Mendez wrote, formally accusing the U.S. of torture.

Those who Manning helped to expose as murders of civilians and torturers, meanwhile, have got off scott free.

Edward Snowden too, the former National Security Agency employee who followed Manning’s lead and leaked reams of secret files to the media exposing what he considered to be wrongdoing of the U.S. and British spy agencies, sparked a global manhunt. He is currently in Russia having been granted temporary asylum by Vladimir Putin. If caught, a trial of Snowden would be a circus, and he could well be frog marched towards fate similar to Manning’s.

Rounding up the whistleblowers themselves is not unusual, but states going for the throats of the journalists and publishers facilitating the leaks appears to be becoming a norm with dangerous new precedents have been set. Glenn Greenwald, for example, the journalist who collaborated with Edward Snowden over the N.S.A. files, reports being hounded by agents, and his partner was detained for nine hours in a London airport on his way home to Brazil.

The U.S. government, as Assange explains, now asserts that publishing whistleblowers’ material amounts to conspiracy. The flow of information, from whistleblower, to journalist, to editor, to publisher, to public, constitutes the crime.

“They have worked out a way to embroil an entire media organization in the U.S. jurisdiction based on any information coming in through one journalist working for that media organization,” says Assange.

WikiLeaks does not publish, and is not registered in the United States, “So how is it that the United States is claiming jurisdiction to prosecute us for these offenses”, he asks.

He describes this a “territorial grab by the United States to say that they can they can go after any media organization anywhere in the world that publishes information that they say is classified.”

The case set the mold for a multi-fronted attack on freedom of speech and information, which Assange presents a “serious threat” to global media scrutiny of the U.S.

Ecuador and the defence of human rights

In the face of such ruthless persecution, it was Ecuador, with a population not much larger than London, that stepped in to defend Assange and take on one of the greatest battles of press freedom in modern times.

Ecuadorean Foreign Minister Ricardo Patiño, who oversaw the events unfolding in London, told teleSUR that Ecuador’s decision to take up Assange’s cause was “faithful to its long tradition of defense of human rights, and in particular the victims of political persecution.”

Though he had also been offered asylum by the president of Tunisia, a few things about Ecuador caught Assange’s attention. The government’s removal of the U.S. base in Manta in 2008 was an example, he says, of how Ecuador had shown a “history of fairly robust principled engagement.” Furthermore, the government had shown a real interest in the Wikileaks project, and even documents that could potentially damage it.

“The Ecuadorean government, unlike any other government, asked us to increase the speed of our publications and to publish more material about Ecuador and not less. That was a very interesting and unexpected sign and the Deputy Foreign Minister came out at that time and said that Ecuador should offer me asylum in Ecuador,” Assange he says.

What’s more, the Ecuadorean government believed the threat that Assange would be extradited and face persecution due to his journalistic activity was very real.

“Ecuador granted diplomatic asylum to Julian Assange after carrying out a fair evaluation of his petition, and considered the risk of political persecution if the opportune methods weren’t taken,” Ecuador’s foreign minister explains.

Several campaign groups joined in the defense of Assange, warning against the future implications of his arrest

The Committee to Protect Journalists wrote an open letter to the British government warning that, “such a prosecution could encourage the government to assert legal theories applying equally to all news media, which would be highly dangerous to the public interest. History shows that Congress didn’t intend the law to apply to news reporting.”

1,000 days later, Patiño is still unwavering in his conviction to grant asylum to Assange, and reaffirms to teleSUR Ecuador’s commitment to keep up the fight.

“We can’t say we’ve completed our mission until Julian Assange recuperates his liberty. 1,000 days have passed, not a single day more should,” he says, highlighting how the period has affected the Wikileaks frontman, afflicting his deteriorating health.

The New Latin America Challenges the Old Order

What began as a question of the right to publish the truth without political persecution morphed into a test of thuggish bullying, and almost resulted in an unprecedented violation of diplomatic codes.

On 15 Aug. 2012, the Ecuadorean embassy received a note from the British government. It threatened to “take action to arrest Mr Assange in existing facilities of the Embassy.”

“We sincerely hope that we do not reach that point, but if you are not capable of resolving this matter of Mr Assange’s presence in your premises, this is an open option for us,” the letter continued ominously.

That night, police descended on the Knightsbridge street, “swarming into the building through the internal fire escape,” Assange wrote.

The threat of incursion into the sovereign territory was unheard of, and intended to intimidate the little Latin American nation. But backed up by 23 out of 26 Organization of American States countries who voted to condemn the move, and with the support of regional blocs such as ALBA and Unasur, Ecuador did not flinch. The solid combined response was a reflection of how far Latin America had come since colonial times, which, Patiño noted grimly, “are over.”

“Such a positive, supportive and coordinated response to episodes like this, where the elemental principles of the right are brought into question, like the respect of sovereignty of countries, reinforces the position Latin America in the world,” Patiño says.

“With the decision to grant asylum to Julian Assange, Ecuador demonstrated that it is a free and democratic state, not subject to any type of external pressures, independent of any interests other than of its people, sovereign in its politics and laws.”

The British bulldog strategy only served to reinforce what the Wikileaks cables first revealed: the moral weakness of the greatest powers in the western world. As Patiño noted, “The United Kingdom did not complete its threat,” and Ecuador will continue protecting Julian for “as long as necessary” and “until Julian Assange arrives at a safe place.”

Wikileaks: an information service not a criminal conspiracy

Although Assange and Wikileaks have since fallen out with, and been maligned by, certain publications and organizations over the handling of the leaked materials, the work that they continue to do is unparalleled, and has ripped away previous boundaries of data journalism.

“Wikileaks performed a public service by posting the documents on the web, as have the newspapers that spent weeks analyzing that material,” wrote media commentator Roy Greenslade.

Millions of documents, spilling legions of secrets, that otherwise would have been consigned to the furthest, dustiest corners of U.S. ministries.

And as he continues to languish in the embassy, despite a veritable media campaign against his character, it looks as if the tide could be turning for the Wikileaks founder.

“There is a growing realization that what is happening here is really unjust. You cannot have someone detained in Europe without charge for four-and-a half years,” he says. “Everyone can see that there is something wrong with that.”

(From: Telesur)